4905

Free-breathing T1ρ Quantification in the Pancreas1Department of Physics & Atmpspheric Science, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada, 2Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada, 3BIOTIC, Nova Scotia Health, Halifax, NS, Canada, 4Department of Digestive Care & Endoscopy, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada, 5Nova Scotia Health, Halifax, NS, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Relaxometry, Pancreas, T1rho

T1ρ quantification in the pancreas is largely unexplored due to the difficulty of compensating for breathing motion. In this study we demonstrate a free-breathing T1ρ technique for use in the abdomen which is able to quantify T1ρ in the pancreas without respiratory gating, through the use of golden-angle radial sampling. The technique was validated in phantoms and tested in three healthy volunteers. T1ρ values in the liver and spleen agreed with recent literature, while differences in T1ρ values in the pancreas may be related to the use of free breathing instead of respiratory gating.

Introduction

T1ρ quantifies the spin-lattice relaxation time in the rotating frame of reference and is sensitive to chemical exchange processes1, macromolecular content2, and fibrotic changes3,4. While T1ρ has been relatively well explored in areas of the body such as the knee5 and head6, acquiring T1ρ -weighted images in the abdomen has proven more challenging due to the presence of respiratory motion.T1ρ quantification of the liver has begun to gain popularity, particularly for staging fibrosis7, with recent investigations using free-breathing techniques7,8, but its utility in the pancreas is still largely unexplored. T1ρ quantification has been shown to be an early indicator of cell death9,10 and so may have the potential to aid in diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and monitoring of treatment response11.

One recent publication has used respiratory-gated T1ρ mapping of the pancreas to distinguish between healthy tissue and chronic pancreatitis12. However, respiratory gating can be challenging in large patients or patients with irregular breathing, and it decreases scan efficiency. Additionally, the effect of gating on prepared contrast is not well understood, with few studies utilizing this technique13.

We have implemented a free-breathing T1ρ sequence based on golden angle radial sampling, “LAVA-Star T1ρ”, to enable motion-robust T1ρ imaging of the pancreas without respiratory gating. Presented here is a pilot study validating the technique, which we aim to deploy in a clinical study of patients with pancreatic cancer in the near future.

Methods

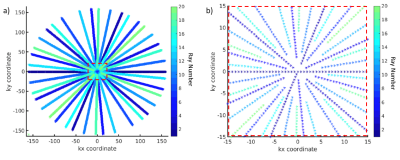

The free-breathing T1ρ sequence was based on LAVA-Star14, a 3D FSPGR imaging sequence with a golden-angle based radial sampling pattern15, and modified to include a composite RF T1ρ preparation pulse16. A Cartesian MAPSS17 T1ρ sequence with an identical preparation module served as a gold standard for validation of quantitative results in phantoms.Since T1ρ contrast is prepared before the imaging sequence and decays during acquisition, sampling the centre of k-space only at the start of image acquisition is essential for retaining T1ρ contrast in the images. To this end we employed a KWIC (k-space weighted image contrast) filter18 for reconstruction of the images, to discard increasing amounts of data from the centre of k-space at each successive ray (Figure 1).

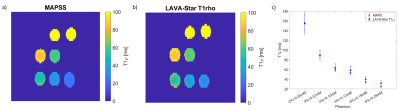

All imaging was performed on a 3T MR750 scanner (GE Healthcare) with a 32-channel cardiac coil. To determine optimal filter parameters, T1ρ maps of phantoms with varying concentrations of gelatin and MnCl2 were compared to those generated by the MAPSS sequence (Figure 2). Acquisitions used spin-lock durations (TSL) of 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 ms with a spin-lock frequency of FSL=350Hz. A T1 recovery time of 600ms was applied after each shot, with 100 rays acquired per preparation and 200 per slice across 2 shots. The parameters which returned the T1ρ map most similar to MAPSS were selected; this yielded a KWIC filter in which the centre point of k-space was kept for only the first ray. This filter was used in reconstruction of all subsequent LAVA-Star T1ρ data.

Once the sequence was validated against MAPSS, it was tested on three healthy volunteers (3F: ages 21, 26, and 36y) who consented to be imaged under an REB-approved protocol. These scans used the same T1ρ preparation as the phantom scans, with FOV=40mm, matrix size=200x200, and 34-44 slices depending on the size of the subject.

T2-weighted anatomical images were also acquired using a respiratory-triggered FSE to aid in drawing regions of interest (ROIs) on the anatomy. The software 3D Slicer19 was used to manually place ROIs on the pancreas (10 mm diameter), liver (40mm diameter), and spleen (30mm diameter) using the anatomical image of each subject (Figure 3a). These ROIs were then transferred to the T1ρ maps, with mean and standard deviation of the ROIs extracted using the same software.

Results & Discussion

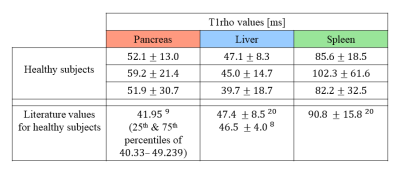

An example set of data from one of the healthy volunteers is displayed in Figure 3.Table 1 lists the T1ρ values extracted from all ROIs, and compares them to those reported in recent literature. The T1ρ values extracted from the spleen and liver of our subjects were found to be comparable to those published in recent studies. The pancreatic T1ρ values are not as congruent with those reported by Sun et al.9, though this discrepancy may be due use of respiratory triggering instead of free-breathing, or other differences in scan parameters such as the spin-lock frequency.

The LAVA-Star sequence does supports a self-gating navigator14, however this currently cannot be used in conjunction with the preparation module. Future work will involve implementing this technique into LAVA-Star T1ρ to compare the effects of self-gating on the image quality and prepared contrast.

In addition to validating LAVA-Star T1ρ in healthy volunteers, we also tested it in a group of three patients diagnosed with chronic pancreatitis (1F aged 83y, 2M aged 43y and 50y). However, due to atrophy of the pancreas and residual motion artifacts we were unable to reliably identify an ROI in the pancreas for these participants.

Conclusion

We have successfully demonstrated a free-breathing T1ρ sequence with golden angle radial acquisition that is able to measure T1ρ values in the pancreas. This pilot study serves as validation of the sequence, and further improvements may enable its evaluation in clinical population.Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided by a Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation Establishment Grant.

References

- Jin T, Autio J, Obata T, Kim SG. Spin-locking versus chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI for investigating chemical exchange process between water and labile metabolite protons. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(5):1448-1460. doi:10.1002/mrm.22721

- Duvvuri U, Kudchodkar S, Reddy R, Leigh JS. T(1rho) relaxation can assess longitudinal proteoglycan loss from articular cartilage in vitro. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10(11):838-844. doi:10.1053/joca.2002.0826

- Wang YX, Yuan J, Chu ES, et al. T1rho MR imaging is sensitive to evaluate liver fibrosis: an experimental study in a rat biliary duct ligation model. Radiology. 2011;259(3):712-719. doi:10.1148/radiol.11101638

- Hou J, Wong VW, Qian Y, et al. Detecting Early-Stage Liver Fibrosis Using Macromolecular Proton Fraction Mapping Based on Spin-Lock MRI: Preliminary Observations. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022;10.1002/jmri.28308. doi:10.1002/jmri.28308

- Wáng YX, Zhang Q, Li X, Chen W, Ahuja A, Yuan J. T1ρ magnetic resonance: basic physics principles and applications in knee and intervertebral disc imaging. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2015;5(6):858-885. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2015.12.06

- Menon RG, Sharafi A, Windschuh J, Regatte RR. Bi-exponential 3D-T1ρ mapping of whole brain at 3 T. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1176. 2018 Jan 19. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-19452-5

- Hou J, Wong VW, Qian Y, et al. Detecting Early-Stage Liver Fibrosis Using Macromolecular Proton Fraction Mapping Based on Spin-Lock MRI: Preliminary Observations [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jun 26]. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022;10.1002/jmri.28308. doi:10.1002/jmri.28308

- Sharafi A, Baboli R, Zibetti M, et al. Volumetric multicomponent T1ρ relaxation mapping of the human liver under free breathing at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2020;83(6):2042-2050. doi:10.1002/mrm.28061

- Hakumäki JM, Gröhn OH, Tyynelä K, Valonen P, Ylä-Herttuala S, Kauppinen RA. Early gene therapy-induced apoptotic response in BT4C gliomas by magnetic resonance relaxation contrast T1 in the rotating frame. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9(4):338-345. doi:10.1038/sj.cgt.7700450

- Kettunen MI, Sierra A, Närväinen MJ, et al. Low spin-lock field T1 relaxation in the rotating frame as a sensitive MR imaging marker for gene therapy treatment response in rat glioma. Radiology. 2007;243(3):796-803. doi:10.1148/radiol.2433052077

- Kooreman ES, Tanaka M, Ter Beek LC, et al. T1ρ for Radiotherapy Treatment Response Monitoring in Rectal Cancer Patients: A Pilot Study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(7):1998. Published 2022 Apr 2. doi:10.3390/jcm11071998

- Sun S, Zhou N, Feng Y, et al. Evaluation of Chronic Pancreatitis With T1 ρ MRI: A Preliminary Study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;53(2):577-584. doi:10.1002/jmri.27302

- Vietti Violi N, Hilbert T, Bastiaansen JAM, et al. Patient respiratory-triggered quantitative T2 mapping in the pancreas. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50(2):410-416. doi:10.1002/jmri.26612

- Ichikawa S, Motosugi U, Kromrey ML, et al. Utility of Stack-of-stars Acquisition for Hepatobiliary Phase Imaging without Breath-holding. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2020;19(2):99-107. doi:10.2463/mrms.mp.2019-0030

- Feng L. Golden-Angle Radial MRI: Basics, Advances, and Applications. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2022 Jul;56(1):45-62. doi: 10.1002/jmri.28187

- Dixon WT, Oshinski JN, Trudeau JD, Arnold BC, Pettigrew RI. Myocardial suppression in vivo by spin locking with composite pulses. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(1):90-94. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910360116

- Li X, Han ET, Busse RF, Majumdar S. In vivo T(1rho) mapping in cartilage using 3D magnetization-prepared angle-modulated partitioned k-space spoiled gradient echo snapshots (3D MAPSS). Magn Reson Med. 2008;59(2):298-307. doi:10.1002/mrm.21414

- Song HK, Dougherty L. k-space weighted image contrast (KWIC) for contrast manipulation in projection reconstruction MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(6):825-832.

- Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30(9):1323-1341. doi:10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001

- Hectors SJ, Bane O, Stocker D, et al. Splenic T1ρ as a noninvasive biomarker for portal hypertension. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2020;52(3):787-794. doi:10.1002/jmri.27087

Figures

Figure 2. T1rho maps of phantoms acquired with the Cartesian MAPSS sequence (a) and the LAVA-Star T1rho sequence (b). T1rho maps are masked based on signal intensity. The two sequences yield comparable T1rho values in all phantoms (c). Phantom labels denote concentration of gelatin [%] and MnCl2 [mM] in each phantom.

Figure 3. Example data from one of the subjects. a) T2-weighted anatomical FSE image used for placing ROIs, with pancreas ROI shown in red. b) LAVA-Star T1rho-weighted image with TSL=0. c) LAVA-Star T1rho map with mask around abdomen.