4883

Relaxation Rate MR Contrast of Metal-Organic Framework or USPIO Labelled Melt Electrowritten Polycaprolactone Scaffolds1Department of Nuclear Medicine, School of Medicine, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 2Medical Materials and Implants, Department of Mechanical Engineering, TUM School of Engineering and Design, & Munich Institute of Biomedical Engineering, Technical University of Munich, Garching, Germany, 3School of Natural Sciences and Catalysis Research Center, Technical University of Munich, Garching, Germany, 4Biomechanics, Department of Materials Engineering, TUM School of Engineering and Design, Technical University of Munich, Garching, Germany, 5Chair of Bioseparation Engineering, School of Engineering and Design, Technical University of Munich, Garching, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Contrast Mechanisms, Preclinical, Tissue Engineering

Polycaprolactone scaffolds were melt electrowritten with and without included metal-organic frameworks (MOF) or nanoparticles (USPIO). MR images and relaxation rate (R1, R2, R2*) maps were acquired of scaffolds in agar and blood. Pure polycaprolactone showed weak or no contrast. Addition of MOF or USPIOs produced strong T2* contrast. Tensile properties were preserved up to 0.2 w/w% USPIOs. MOFs produced strong w/w% dependent antibacterial effects when included in scaffolds.

Introduction

Melt electrowriting (MEW) is a method for fabricating complex microstructures and scaffolds by extruding polymer jets and accelerating them with a voltage onto a moving collector plate in layered patterns. Polycaprolactone (PCL) is a biocompatible and biodegradable polymer with applications in drug delivery and tissue engineering, and is the gold standard polymer for MEW. However, pure PCL has poor MR contrast with biological tissues, which would be highly beneficial for visualization and monitoring of implanted scaffolds for clinical translation. To improve MEW PCL scaffold MR contrast, this work includes ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) nanoparticles, or metal-organic frameworks (MOF) that additionally show antibacterial activity. The resulting scaffolds have promise for use in tissue engineering of vascular grafts or heart valves.Methods

Polymer Preparation: USPIOs were synthesized [1] with size <= 10 nm, dissolved in acetone with PCL (w/w% = 0.1, 0.2, 0.3) and dried. MOF NH2-MIL-88B-(Fe) (MIL-88Fe) was synthesized and post-synthetically loaded with silver particles, producing NH2-MIL-88B-(Fe/Ag) (MIL-88Ag). Similarily, MOF NH2-MIL-125-(Ti) was synthesized and loaded with iron particles, producing NH2-MIL125-(Ti/Fe) (MIL-125Fe). MOFs (w/w% = 5) were dispersed with PCL in chloroform and dried.MEW: Pure and doped PCL was extruded through a needle at 85 °C over a grounded metal collector plate [2] with ≈5 kV applied. 8-layer mesh patterns (Fig. 1) were written for MRI and biological testing, and straight lines for tensile testing.

MRI: A preclinical 7 T magnet and 10 mm RF solenoid coil were used, with samples in glass tubes. Pure PCL, USPIO [3], and MOF meshes were embedded in agar (Fig. 1). Pure PCL and USPIO meshes were also immersed in human blood. T1-T2*w (GRE) images, and R2 (MSME), R2* (MGE), and R1 (IR-FSE) maps were acquired. For pure PCL and MOF meshes, additional T1‑T2*w images with varied echo times and slice thicknesses were acquired.

Tensile Strength: The stress-strain curve was measured to assess the impact on Young’s modulus and ultimate tensile strength of USPIO-PCL [3].

Antibacterial: Printed samples were inoculated with S. epidermidis, S. aureus, or E. coli, incubated 3 hours at 37 °C. Bacteria were detached, plated on agar, incubated another 72 hours, and their colony forming units counted.

Results

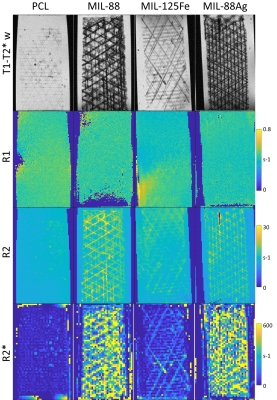

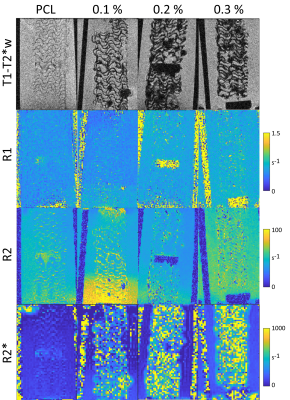

T1-T2*w: Pure PCL scaffold structure is faintly visible against agar (Fig. 2), and MIL-88 inclusion substantially enhances this contrast, increasing with TE and decreasing with slice thickness, which remains visible with up to 8 mm thick slices (Fig. 3). MIL-88 has similar contrast, while MIL-125 has less. Scaffolds have increasing contrast with USPIO w/w% in agar [3] and in blood (Fig. 4). Structure of scaffolds is resolved for pure PCL in higher-resolution images (Fig. 2 with 0.063x0.063x0.3 mm3 voxels and Fig. 4 with (0.1 mm)3 voxels), but becomes less clear with higher USPIO levels or the MIL-88 MOF.R1: Neither pure PCL, nor included MOF or USPIOs, produce substantial R1 contrast.

R2: Pure PCL lacks contrast with agar but is slightly visible in blood. MIL-88 and MIL-125 inclusion improves contrast with agar, and MIL-88 allows scaffold structure to be resolved (Fig. 2). Added USPIOs improve contrast with agar but not blood (Fig. 4).

R2*: Pure PCL lacks contrast with agar (Fig. 2) but is faintly visible in blood (Fig. 4). MOF (particularly Fe-based MIL-88) and USPIOs both produce strong contrast with agar and/or blood. With USPIO inclusion, R2* increases with w/w% up to 0.2%. For 0.1% USPIO vs. pure PCL scaffolds, mean R2* in blood were 182 s-1 vs. 68 s-1, and in agar were 197 s-1 vs. 16 s-1. With 5% MIL-88 and pure PCL scaffolds in agar, mean R2* were 276 s-1 vs. 28 s-1.

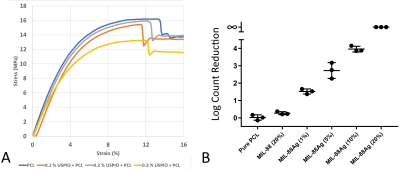

Tensile Strength: Stress-strain curves (Fig. 5), ultimate tensile strength and Young’s modulus are similar up to 0.2% w/w USPIOs in PCL [3].

Antibacterial: Increasing Ag-loaded MOF w/w% correlates with reduced bacterial count of the inoculated samples (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Lack of relaxation-rate contrast for pure PCL scaffolds suggests that the contrast in T1-T2*w images is due to lower proton density than agar or blood. Addition of USPIOs or Fe-based MOFs increases this contrast, making scaffolds visible even with image slices much thicker than the scaffolds.The exact relaxation rates measured will depend on temperature, details of scaffold structure, density, and thickness, agar preparation, image slice thickness and their alignment with the scaffolds. However, the primary imaging results of this work are qualitative, and are expected to be similar in vivo.

Conclusion

Pure PCL MEW scaffolds have poor MR T1, T2, or T2* contrast and appear faintly in T1-T2*w images when embedded agar or blood, likely due to lower proton density. Inclusion of USPIOs or MOF strongly increases the T2*w contrast of PCL scaffolds, with concentration-dependence up to 0.2% w/w USPIOs, and stronger contrast for Fe-based MIL-88 than Ti-based MIL-125 MOF. Ag-loaded MIL-88 shows strong concentration-dependent anti-bacterial effects. These results suggest great promise for MR-visualization and functionalization of MEW PCL scaffolds for in vivo applications.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] Thomas JA, Schnell F, Kaveh-Baghbaderani Y, Berensmeier S, Schwaminger SP. 2020. Immunomagnetic Separation of Microorganisms With Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Chemosensors 8

[2] Saidy NT, Wolf F, Bas O, Keijdener H, Hutmacher DW, Mela P, De‐Juan‐Pardo EM. 2019. Biologically Inspired Scaffolds for Heart Valve Tissue Engineering via Melt Electrowriting', Small 15

[3] Mueller KAM, Topping GJ, Schwaminger SP, Zou Y, Rojas-González DM, De-Juan-Pardo EM, Berensmeier S, Schilling F, Mela P. 2021. Visualization of USPIO-labeled melt-electrowritten scaffolds by non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging. Biomaterials Science 9

Figures

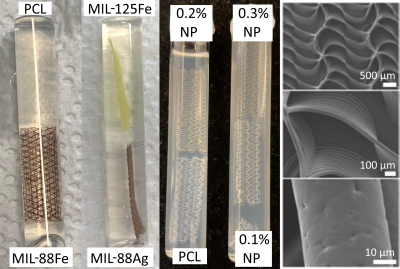

Figure 1: Photographs of melt-electrowritten meshes of polycaprolactone (PCL) doped with metal organic frameworks or ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (NP) embedded in agar in 10 mm sample tubes, and scanning electron micrographs of a scaffold [3]. Pure PCL scaffolds are colorless, Fe-based MIL-88 scaffolds are dark red, the Ti-based MIL-125 scaffold is yellow, and NP-doped scaffolds have a w/w dependent yellow-brown coloration.

Figure 2: T1-T2*w images (GRE) resolve the scaffold structure of MEW PCL scaffolds in agar, with stronger contrast for MOF scaffolds, and strongest for MIL-88 scaffolds. R1 maps show no contrast between PCL and agar. R2 maps resolve the scaffolds of PCL with MOF. R2* shows no contrast with pure PCL, can partially resolve the structure of MIL-125Fe scaffolds, and shows strongest contrast with Fe-based MIL-88 scaffolds but does not resolve the scaffold structure.

Figure 3: FLASH T1-T2*w MRI of MEW scaffolds of PCL doped with MIL-88 (5% w/w), with various echo times and slice thicknesses, with (0.5 mm)2 in plane resolution. These images better reflect plausible clinical image contrast from PCL scaffolds than do the smaller voxels in other figures. With moderate T2* contrast at TE = 8 ms, the ≈0.4 mm thick scaffolds remain visible against background agar even with 8 mm thick image slices.

Figure 4: T1-T2*w images (GRE) resolve the scaffold structure of Pure PCL and USPIO doped (w/w % marked) scaffolds in human blood, with stronger contrast for labelled scaffolds. R1 maps show no or minimal contrast between scaffolds and blood. R2 maps show poor to moderate contrast without detail of the scaffolds. R2* shows no or minimal contrast with pure PCL and strong and increasing contrast with USPIO weight %, but does not resolve the scaffold structure.

Figure 5: A: Stress-strain curves of MEW PCL with varied USPIO content [3]. Mechanical properties of PCL are preserved up to 0.2% w/w USPIOs. 0.3% shows reduced ultimate tensile strength and Young’s modulus. B: E. coli colony-forming unit (CFU) count reduction (vs. pure PCL) determined from serial dilution in PBS that were detached from printed samples by vortexing. Bacterial reduction shows dependency on weight fraction of Ag-loaded NH2-MIL-88B-(Fe) MOF in PCL of the printed samples, indicating an antibacterial effect from Ag.