4877

Resting perfusion measures in patients with steno-occlusive disease; comparing two contrast agents Gadolinium and hypoxia-induced dOHb1Physiology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 3University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4Department of Neuroradiology, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Synopsis

Keywords: Contrast Agent, Perfusion

Dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion imaging is clinically acquired using Gadolinium based contrast agents (GBCA), however, there remain many drawbacks. We show that in patients with steno-occlusive disease perfusion imaging using hypoxia-induced dOHb have a high degree of similarity to those obtained using GBCA.Introduction

In the presence of cerebrovascular steno-occlusive disease (SOD), inadequate collateral blood flow may result in cerebral ischemia. Cerebral perfusion adequacy can be assessed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to obtain relative perfusion measures such as mean transit time (rMTT), cerebral blood volume (rCBV) and cerebral blood flow (rCBF) using dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) analysis. Gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCA) are used currently but a non-invasive alternative, hypoxia- induced changes in deoxyhemoglobin concentration ([dOHb]) has also been proposed as a contrast agent1. Here we compare DSC perfusion measures obtained using both [dOHb] and GBCA as contrast agents in patients with steno-occlusive disease.Methods

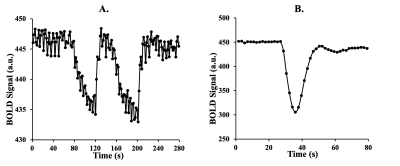

After obtaining ethics approval and informed consent, we recruited 10 patients between the ages of 39 and 74 (mean (SD) = 57 (13.39), median = 60.5), 2 F) with known steno occlusive disease. The MR images were acquired using a 3-Tesla scanner with a 32-channel head coil and an automated gas system capable of controlling end-tidal partial pressure of oxygen (PETO2) while maintaining normocapnia (RespirAct™)2,3. The protocol consisted of a high resolution T1-weighted anatomical scan followed by 2 identical BOLD sequence scans. The first BOLD scan sequence was acquired during PETO2 manipulation while the second scan was acquired at normoxia following an intravenous injection of GBCA sequence with the following parameters: TR = 1800 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 80◦, 50 slices and voxel size = 2.5x2.5x2.5 mm. The acquired images were analyzed using Analysis of Functional Neuroimaging (AFNI)4. An arterial input function was chosen manually over a voxel near the middle cerebral artery for both methods (Figure 1). Segmentation of gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) were carried out using SPM8 software. Perfusion measures such as MTT and rCBF were calculated using a standard tracer kinetic model 5. rCBF was then calculated using the central volume theorem as rCBF = rCBV/MTT. Maps of perfusion measures were created using AFNI software and overlayed onto their respective anatomical images.Results

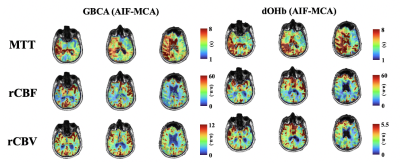

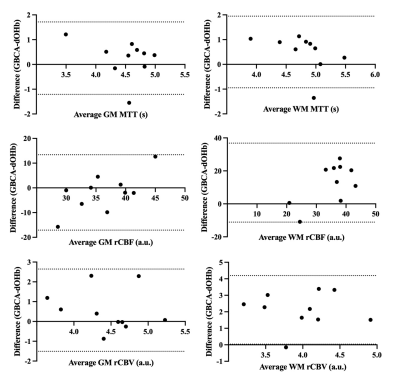

The calculated perfusion measures displayed similar voxel-wise proportional changes in BOLD signal throughout the brain. The spatial distributions of each perfusion measure generated by hypoxia-induced changes in dOHb and those of GBCA were consistent, providing the same distribution of perfusion measures that followed the known cerebrovascular pathology in each individual (Figure 3). Bland-Altman analysis between GBCA and hypoxia-induced dOHb suggest there is little bias or difference between methods (Figure 3).Discussion

This initial comparison of perfusion measures in the same patient using DSC with both hypoxia-induced changes in dOHb and GBCA as contrast agents showed similar spatial distributions for each perfusion measure. As the [dOHb] change generated in the lungs is restored to oxyhemoglobin on the next pass through the lungs, resolving the susceptibility, dOHb can be used in successive tests, whereas GBCA can only be used for a single test. Thus, [dOHb] may support a sufficient frequency of cerebral perfusion examinations to follow the natural history and evolution of cerebrovascular disease. Furthermore, it may be an alternative DSC for patients not tolerant of GBCA.Conclusion/summary of findings

Hypoxia-induced change of [dOHb] is a novel DSC agent providing similar perfusion maps and measures to those using intravenously injected GBCA in the same individuals.Acknowledgements

References

1. Sayin ES, Schulman J, Poublanc J, et al. Investigations of hypoxia-induced deoxyhemoglobin as a contrast agent for cerebral perfusion imaging. Hum Brain Mapp. Oct 29 2022;doi:10.1002/hbm.26131

2. Fisher JA. The CO2 stimulus for cerebrovascular reactivity: Fixing inspired concentrations vs. targeting end-tidal partial pressures. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. June 1, 2016 2016;36(6):1004-1011. doi:10.1177/0271678x16639326

3. Fierstra J, Sobczyk O, Battisti-Charbonney A, et al. Measuring cerebrovascular reactivity: what stimulus to use? J Physiol. Dec 1 2013;591(Pt 23):5809-21. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2013.259150

4. Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. Jun 1996;29(3):162-73.

5. Poublanc J, Sobczyk O, Shafi R, et al. Perfusion MRI using endogenous deoxyhemoglobin as a contrast agent: Preliminary data. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2021;n/a(n/a)doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.28974

Figures