4863

3D LGE MRI at 3T for the Detection of Chronic Scars after RF Ablation in the Right Atrium: Assessment of Precision in a Porcine Study1Division of Medical Physics, Department of Radiology, University Medical Center Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany, 2Institute for Experimental Cardiovascular Medicine, University Heart Center Freiburg Bad Krozingen, and Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Heart, Arrhythmia

RF ablation is an established treatment option for cardiac arrhythmia. After RF ablation the scar can be assessed with LGE MRI. However, imaging of scars in the right atrium (RA) remains difficult due to the small geometry. In this animal study, we assessed the conspicuity of chronic RA scars by comparing scar extent on MRI to ex vivo anatomical dissected preparations. We show, the detection of chronic RF ablation scars in the RA is feasible but with limited precision. The presented comparison to gross histology provides and important evaluation of RF ablation scar conspicuity in LGE MRI.Introduction

Radiofrequency (RF) ablation is an established treatment option for cardiac arrhythmia. After RF ablation the extent of the scar can be assessed with late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) MRI which has been successfully demonstrated in the left atrium (LA), in pulmonary vein isolation, and in the left ventricle1–5. However, LGE imaging of scars in the right atrium (RA) is more difficult due to the smaller geometry and thin walls of the RA, and only few studies have evaluated LGE for the detection of chronic scars in the RA6,7. In this animal study in swine, we assessed the conspicuity of chronic RA scars after RF ablation by comparing scar extent on LGE MRI to ex vivo gross anatomical dissected preparations.Methods

Six animals underwent MRI after RF-based atrial ablation using clinical equipment employed in atrial fibrillation patients to better understand atrial scar development. MRI was performed at a clinical 3T system (Siemens PrismaFit) 8 weeks after ablation on anaesthetized pigs. In a subset of animals, baseline MRI data was acquired before ablation as controls. A 3D FLASH Sequence with inversion recovery preparation, ECG and respiratory gating was acquired 20 min after contrast agent administration (TR = 3.0 ms, TE = 1.4 ms, a = 15°, BW = 820 Hz/px, FoV = 308 x 340 x 130 mm³, matrix = 280 x 320 x 52). Four animals received 0.125 mmol/kg of Gadoteridol (ProHance, Bracco) and two animals received 0.25 mmol/kg. The imaging slab was positioned across the RA in transverse slice orientation. After MRI, animals were euthanized and the hearts were excised for gross anatomical and histological analysis of the RA. The scar size was measured in both MRI and gross anatomical preparations. Therefore, MRI data was segmented manually two times: first in a blinded manner and a second time after seeing dissection results. The size of the scar was quantified by the lengths in SI (scar length) and RL (scar width) direction and compared between MRI and dissection. In addition, the contrast to noise ratio (CNR) between the scar and the RA was measured.Results

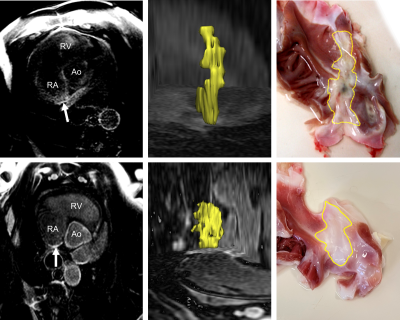

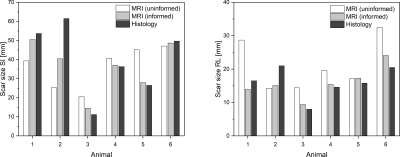

Lesions were applied using contact force sensing catheters, well-defined parameters for energy dosage and experienced clinicians. Surprisingly, lesion outcomes were highly variable. Differences included line start and end locations, continuity of the line, line width, and transmurality. This variability in structural and functional properties could not be easily predicted from intraprocedural or repeat (8 weeks after ablation) in vivo electroanatomical mapping or blinded MRI data. All animals survived the time between ablation and the MRI exam with no major complication. Figure 1 shows a transverse MR image of the RA and the scar (white arrow), a 3D rendering of the segmented scar and the corresponding dissected open RA (view from the endocardium). Figure 2 shows the measured lengths of the scars in SI and RL direction for the uninformed and informed segmentation as well as from histology. The mean difference between the size measured with MRI and histology was (43 ± 32) % in SI direction and (47.8 ± 27.7) % in RL direction. This difference was reduced with the informed segmentation to (13.1 ± 14.6) % in SI direction and (15.6 ± 7.8) % in RL direction. In the two animals that received the higher Gd dose the difference was generally lower by 35.6 % (blinded segmentation) and 8.6 % (informed segmentation). The mean CNR of the scars was 1.5 ± 0.8 (blinded segmentation) and 1.6 ± 0.7 (informed segmentation).Discussion & Conclusion

Chronic scars after RF ablation in the RA can be detected with 3D LGE MRI. However, the low SNR may lead to substantial errors in estimating the size of the scar. Scar sizes were both over- and underestimated which indicates that noise contamination leads to both false negative and false positive selection on the MR images. No relationship was found between the relative error and the scar size, i.e. a larger scar did not lead to a more precise segmentation. Not surprisingly, a higher Gd dose reduced the error, but this needs to be assessed in more subjects. After an informed segmentation, the average error was less than 20 %. Here, the bias of error of the blinded and informed segmentations were generally the same, i.e. both over-/underestimated the scar extent. Previous studies often used signal intensity thresholds relative to SI of the atrial blood pool for automatic segmentation. In this study the CNR between atrial blood and the segmented scar varied strongly between subjects due to differences in physiology and MR acquisition (Gd dose, post Gd delay, IR delay, field strength); thus, a manual adaption of the threshold would become necessary.In general, the detection of chronic RF ablation scars in the RA is feasible with 3D LGE but with limited precision when SNR is low. While the different physiology needs to be taken into account when translating these results to human studies, the presented comparison to gross histology provides and important evaluation of RF ablation scar conspicuity in LGE MRI.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of SFB1425, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation #422681845)References

1. Peters, D. C. et al. Detection of Pulmonary Vein and Left Atrial Scar after Catheter Ablation with Three-dimensional Navigator-gated Delayed Enhancement MR Imaging: Initial Experience. Radiology 243, 690–695 (2007).

2. McGann, C. J. et al. New Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Based Method for Defining the Extent of Left Atrial Wall Injury After the Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52, 1263–1271 (2008).

3. Chubb, H. et al. The reproducibility of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging of post-ablation atrial scar: a cross-over study. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 20, 21 (2018).

4. Tao, S. et al. Ablation Lesion Characterization in Scarred Substrate Assessed Using Cardiac Magnetic Resonance. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 5, 91–100 (2019).

5. Mont, L., Roca-Luque, I. & Althoff, T. F. Ablation Lesion Assessment with MRI. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. Rev. 11, e02 (2022).

6. Ozgun, M. et al. Right Atrial Scar Detection after Catheter Ablation: Comparison of 2D and High Spatial Resolution 3D-late Enhancement Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Acad. Radiol. 18, 488–494 (2011).

7. Harrison, J. L. et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance and electroanatomical mapping of acute and chronic atrial ablation injury: a histological validation study. Eur. Heart J. 35, 1486–1495 (2014).Figures