4854

Impact of Epicardial Adipose Tissue Assessed on Early Left Atrial Dysfunction in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction1Department of Cardiology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China, HarBin, China, 2Phillips Healthcare, Beijing, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Heart, Cardiovascular, Heart failure

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) characterized by heart diastolic dysfunction. Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) has been speculated to play an important role in HFpEF pathophysiological processes. In present study, EAT volume was significantly increased in patients with HFpEF and patients with high risk for developing HFpEF compared with healthy controls, and it was correlated with CMR parameters indicative of diastolic dysfunction, particularly GLS and LA reservoir, conduit, and pump strains. These findings provided compelling evidence for the potential role of EAT in adverse myocardial remodeling and the pathophysiology of HFpEF.

Introduction

Obesity is a major risk factor for the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) 1-3,presenting as diastolic dysfunction that affects about half of patients with heart failure. Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT), a metabolically active visceral fat depot located between the pericardium and myocardium 4,5, has potential cardiotoxic implications via the secretion of proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokines by paracrine, endocrine and vasocrine pathway 6,7,which is associated with heart remodeling and dysfunction 7-9. EAT has been speculated to play an important role in HFpEF pathophysiological processes 10. It was demonstrated that patients with HFpEF had more EAT than those control subjects 11. Recently, studies have revealed that EAT was associated with left atrial (LA) volume and function changes12-14. However, to date, the evidence linking EAT to LA dysfunction in HFpEF is limited.In traditional clinical practice,echocardiography was the most commonly used method for the assessment of atrial structure and function 15,16. However, it was highly susceptible to afterload. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) may offer an accurate and sensitive alternative approach to quantify of LA function. CMR-feature tracking (FT) derived LA strain parameters demonstrated to be associated with epicardial fat 17. In this study, we aimed to investigate the association between EAT and strain parameters derived by CMR-FT in HFpEF.

Methods

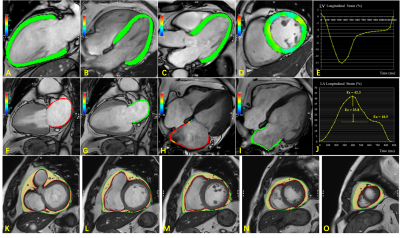

Between January 2021 to May 2022, consecutive adult patients hospitalized with suspected HFpEF who underwent CMR were retrospectively screened for this study. Age- and sex-matched asymptomatic control subjects without known cardiac disease and dysglycemia were recruited. In addition, we enrolled patients without symptoms of HF but at risk for HFpEF given elevated natriuretic peptide levels (NT-pro BNP levels>125 pg/mL or BNP levels>35 pg/mL) as the high-risk group, those patients had at least one comorbidity (Obesity [defined by BMI ≥30 kg/m2], hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, or chronic kidney disease [stage I to stage III]). Philips 3.0T MR platform was used (Ingenia CX, Philips Healthcare, the Netherlands) for all participants. CMR image analysis was performed using the CVI42 post-processing software (Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc., Calgary, Canada). LV global longitudinal strain (GLS) was performed by loading 2-, 3-, and 4-chamber views into the strain module (Fig 1, A-E). LA strain parameters were calculated from the 2- and 4-chamber images with strain module (Fig 1, F-J). The EAT volume analysis were performed on end-diastolic short-axis slices using CVI42 tissue characterization module, ranging from the basal to apical slices. Regions of high-signal intensity between the myoepicardium and parietal pericardium were calculated by a semi-automatic protocol for image post-processing, excluding blood vessels (Fig 1, K-O). Variables and differences were examined using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey–Kramer post-hoc test. Univariable binary logistic regression models were applied to evaluate the relationship between variables and HFpEF. Multivariable binary logistic regression analysis using forward elimination was used to identify potential predictors of the occurrence of HFpEF.Results

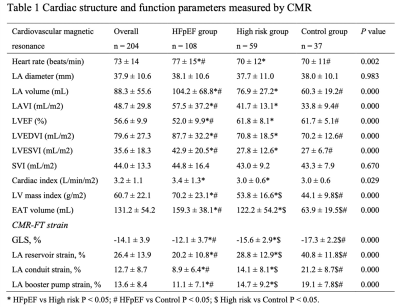

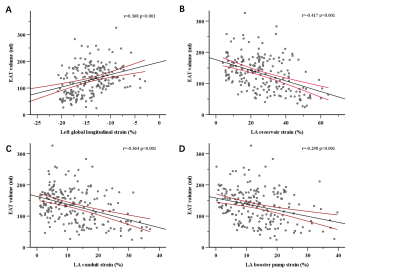

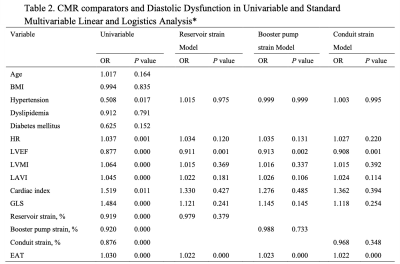

In total, 108 HFpEF patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria, at the same time, 37 healthy volunteers from the same period were selected as the control group, and 59 patients met the inclusion criteria for high-risk group (Table 1). Morphological changes in the HFpEF group when compared with the control group, mainly including LV myocardial remodeling (LV mass index: 70.2 ± 23.1 g/m2 vs. 44.1 ± 9.8 g/m2, P = 0.000; LV end-diastolic volume index: 87.7 ± 32.2 mL/m2 vs. 70.2 ± 12.6 mL/m2, P = 0.000; LV end-systolic volume index: 42.9 ± 20.5 vs. 27.0 ± 6.7, P = 0.000) and LA enlargement (104.2 ± 68.8 vs. 60.3 ± 19.2, P = 0.000). Figure 2 shows correlations between EAT and CMR diastolic functional parameters, that greater EAT volume was associated with lower reservoir, conduit, and booster pump strain (r = -0.417, -0.364 and -0.298, respectively) and impaired LV GLS (r = 0.368, P = 0.000). EAT and LVEF was the independent risk of HFpEF in any of the multivariable models (Table 2).Discussion

Impairment of systolic cardiac function in patients with HFpEF has long been recognized18-20. Various hypotheses have attempted to relate EAT and systolic function. A single study evaluated EAT volume was strongly associated with myocardial systolic dysfunction in subclinical heart failure21. EAT volume was correlated with E/e’ ratio and average e’ velocity from echocardiography22. CMR is the current reference standard method for determining the structure of the heart and its function when compared with echocardiography, which could help to detect subtle dysfunction by feature tracking technology. In our study, we found that greater EAT volume was associated with lower reservoir, conduit, and booster pump strain (r = -0.417, -0.364 and -0.298, respectively) and impaired GLS (r = 0.368, P = 0.000). Furthermore, our results showed that LA strain was strongly correlated with BMI and epicardial fat supporting an association between adiposity and LA strain. If the LA strain measurement method is validated, the ability to reliably detect early changes that may be a precursor, which could clinically detect apparent disease and further have important applications as both a clinical and research tool.Conclusions

EAT is associated with adverse left ventricular remodeling and myocardial systolic dysfunction in patients with HFpEF, and is an independent factor in the development of HFpEF.Acknowledgements

NoneReferences

1. Rao V, Zhao D, Allison M, et al. Adiposity and Incident Heart Failure and its Subtypes: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). JACC Heart failure. 2018;6(12):999-1007.

2. Borlaug B, Jensen M, Kitzman D, Lam C, Obokata M, Rider O. Obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: new insights and pathophysiologic targets. Cardiovascular research. 2022.

3. Sorimachi H, Omote K, Omar M, et al. Sex and central obesity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. European journal of heart failure. 2022;24(8):1359-1370.

4. Pugliese N, Paneni F, Mazzola M, et al. Impact of epicardial adipose tissue on cardiovascular haemodynamics, metabolic profile, and prognosis in heart failure. European journal of heart failure. 2021;23(11):1858-1871.

5. Koepp K, Obokata M, Reddy Y, Olson T, Borlaug B. Hemodynamic and Functional Impact of Epicardial Adipose Tissue in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart failure. 2020;8(8):657-666.

6. Iacobellis G. Local and systemic effects of the multifaceted epicardial adipose tissue depot. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2015;11(6):363-371.

7. Iacobellis G. Epicardial adipose tissue in contemporary cardiology. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2022;19(9):593-606.

8. Iacobellis G, Barbaro G. Epicardial adipose tissue feeding and overfeeding the heart. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif). 2019;59:1-6.

9. Sacks H, Fain J. Human epicardial fat: what is new and what is missing? Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology. 2011;38(12):879-887.

10. Packer M. Do most patients with obesity or type 2 diabetes, and atrial fibrillation, also have undiagnosed heart failure? A critical conceptual framework for understanding mechanisms and improving diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(2):214-227.

11. van Woerden G, Gorter TM, Westenbrink BD, Willems TP, van Veldhuisen DJ, Rienstra M. Epicardial fat in heart failure patients with mid-range and preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(11):1559-1566.

12. Mookadam F, Goel R, Alharthi MS, Jiamsripong P, Cha S. Epicardial fat and its association with cardiovascular risk: a cross-sectional observational study. Heart Views. 2010;11(3):103-108.

13. Kilicaslan B, Ozdogan O, Aydin M, Dursun H, Susam I, Ertas F. Increased epicardial fat thickness is associated with cardiac functional changes in healthy women. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228(2):119-124.

14. Fox CS, Gona P, Hoffmann U, et al. Pericardial fat, intrathoracic fat, and measures of left ventricular structure and function: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2009;119(12):1586-1591.

15. Galderisi M, Cosyns B, Edvardsen T, et al. Standardization of adult transthoracic echocardiography reporting in agreement with recent chamber quantification, diastolic function, and heart valve disease recommendations: an expert consensus document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. European heart journal Cardiovascular Imaging. 2017;18(12):1301-1310.

16. Fuster V, Rydén L, Cannom D, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in partnership with the European Society of Cardiology and in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;57(11):e101-198.

17. Evin M, Broadhouse KM, Callaghan FM, et al. Impact of obesity and epicardial fat on early left atrial dysfunction assessed by cardiac MRI strain analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15(1):164.

18. Obokata M, Reddy Y, Borlaug B. Diastolic Dysfunction and Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Understanding Mechanisms by Using Noninvasive Methods. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2020;13:245-257.

19. Adamczak D, Oduah M, Kiebalo T, et al. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction-a Concise Review. Current cardiology reports. 2020;22(9):82.

20. Nerlekar N, Muthalaly R, Wong N, et al. Association of Volumetric Epicardial Adipose Tissue Quantification and Cardiac Structure and Function. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018;7(23):e009975.

21. Ng A, Goo S, Roche N, van der Geest R, Wang W. Epicardial Adipose Tissue Volume and Left Ventricular Myocardial Function Using 3-Dimensional Speckle Tracking Echocardiography. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2016;32(12):1485-1492.

22. Hachiya K, Fukuta H, Wakami K, Goto T, Tani T, Ohte N. Relation of epicardial fat to central aortic pressure and left ventricular diastolic function in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30(7):1393-1398.Figures

Figure 2: Linear graphs show correlations between epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) and left ventricular global longitudinal strain (A), LA reservoir (B), conduit (C), and booster pump strain (D).

*Variables with P smaller than 0.1 in a univariate linear regression model were further analyzed in a multivariate linear regression model. R denotes Univariate linear regression adjusted R2 and b multivariable standardized regression coefficient.