4852

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for preprocedural planning of percutaneous left atrial appendage closure1Internal Medicine II, Ulm University Medical Center, Ulm, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Arrhythmia, MR-Guided Interventions, LAA closere, preprocedural planning

An isotropic 2D six-point Dixon method was applied for assessment of the left arterial appendix (LAA) morphology prior to LAA closure intervention. Sufficient image quality was achieved even in highly arrhythmic patients allowing for the preinterventional quantification of the LAA dimensions as required for proper closure device selection. MR derived diameters were compared to periprocedurally TEE and XR derived values, which were in good agreement. Further, optimal XR angulation providing projections perpendicular to the envisaged landing zone could be identified.Introduction

Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage (LAA) facilitates stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation (1–3). Optimal device selection and positioning are often challenging due to highly variable od the LAA morphology. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and x-ray fluoroscopy (XR) represent the current gold standard imaging techniques. However, underestimation of relevant parameters is frequently observed (4–7). Alternative assessment based on 3-dimensional computer tomography has been reported more accurate but increases radiation and contrast agent exposure (5, 8, 9). This study investigated the application of non-contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) to support preprocedural planning for LAA closure (LAAc).Methods

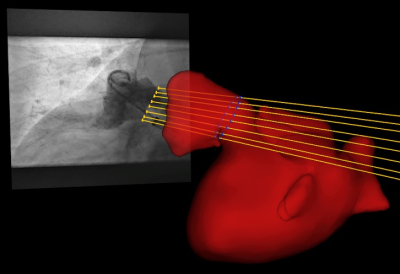

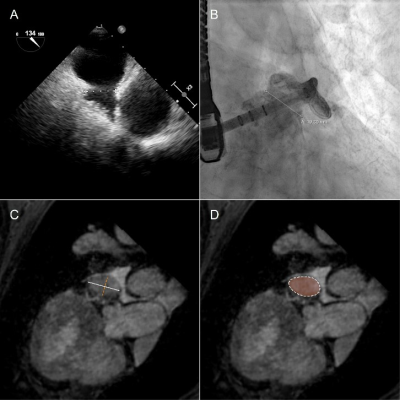

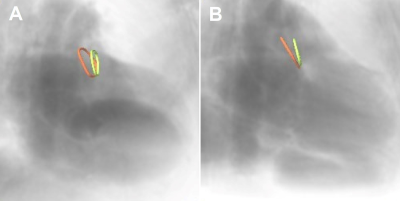

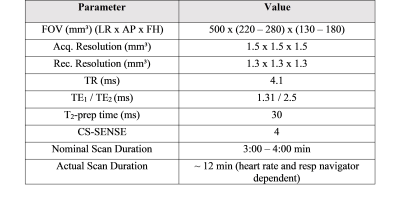

This pilot study involved 13 patients (85% male, 76 ± 9 years) with atrial fibrillation undergoing LAAc. Routinely, the LAA of the patients was measured periprocedural with 2D TEE at ~45°, ~90°, and ~135° and XR using routine angulation. In case of imperfect visualization of the LAA, additional XR projections with angulations as suggested by cMRI were acquired for device dimension prediction. To investigate the applicability of cMRI to support the planning of LAAc, cMRI was acquired preprocedurally at a resolution of 1.33 mm3 with a two-point Dixon sequence (Table1) on a 3T (Achieva 3.0T, dStrean, R5.6, Philips Medical Systems B.V., Best, The Netherlands) using a non-contrast-enhanced protocol (10). For validation of the approach, the agreement between cMRI-based measurements and XR-based measurements was assessed. In this context, the landing zone as determined by periprocedural XR was localized in the co-registered 3D cMRI (Figure 1), and the maximum diameter, as well as the diameters derived from the perimeter and the area of the LAA quantified based on the cMRI data. Resulting values were compared to the XR derived dimensions. The reliability of these measurements was evaluated using the intraclass coefficient (icc) derived from the measurements of three different readers. After proving the general agreement between XR and cMRI derived measurements, the potential of cMRI to support the preprocedural planning of LAAc was investigated. Here, the maximum, and perimeter- and area-derived diameters were quantified at the location of the cMRI identified landing zone and compared to the respective peri-procedurally derived XR- and TEE values (Figure 2). Further, optimal XR angulations with the projection direction perpendicular to the landing zone determined preprocedurally based on cMRI (Figure 3) were compared with the XR angulations finally used periprocedurally for LAA measurement. The statistical significance of differences between the modalities was assessed applying a two-tailed paired t-test, respectively Wilcoxon signed-rank test as appropriate, depending on the results of Leven’s test for equal variances and Shapiro-Wilk test for normality. The correlation was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r). A P-value <0.05 was assumed statistically significant. The mean value (m) and the standard deviation (±, std) of the differences are reported.Results

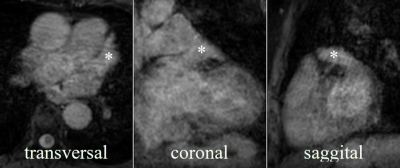

The LAA could be identified, segmented, and measured on the non-contrast enhanced cMRI in all patients regardless arrhythmia (Figure 4). At the landing zone derived from XR, the compatibility of the cMRI-based diameters derived from the perimeter (m=0.2±1.7mm, p=0.73) and area (m=-0.6±1.5mm, p=0.23) with XR-based measurements was high, strongly correlated (r>0.9, p<0.05), with excellent interrater reliability (icc>0.88). The maximum cMRI-based diameters exceeded the XR-based diameters (m=2.1±2.6mm, p=0.73; r=0.83, p<0.05). Similar results were obtained for the application of cMRI for preprocedurally planning. Diameters derived from the perimeter (m=0.9±2.8mm, p=0.32; r=0.77, p<0.05) and area (m=0.3±2.6mm, p=0.7; r=0.79, p<0.05) based on cMRI showed great congruency compared to those measured by XR, whereas the maximum diameter exceeded (m=3.3±3.5mm, p<0.05; r=0.68, p<0.05). Compared to TEE assessment, cMRI-derived diameters were significantly larger (maximum: m=4.6±2.9mm, p<0.05; r=0.77, p<0.05; perimeter-derived: m=2.2±2.0mm, p<0.05; r=0.87, p<0.05, area-derived: m=1.6±1.7mm, p<0.05; r=0.90, p<0.05). C-arm angulations determined by cMRI agreed with those used during the procedures (84%) as to whether the angulation should be within the classical range. In about 60% of the cases, the angulation was close to or within the angular range suggested for LAAc planning. In about 40% of cases it was necessary to additionally acquire XR views with angulation as predicted by cMRI.Discussion & Conclusion

This small pilot study demonstrates the potential of non-contrast-enhanced cMRI to support the preprocedural planning of LAAc. With the suggested non-contrast-enhanced protocol, it was possible to 3D image the LAA of patients with atrial fibrillation using cMRI. Based on cMRI, the shape of the LAA could be assessed in 3D, and a landing zone with respective dimensions could be identified as well as optimal XR angulations. The agreement of measurements based on XR and cMRI at the same landing zone shows the accuracy of a cMRI-based measurement related to a routinely used measurement technique. As planning tool, the landing zone defined based on cMRI, diameter measurements based on LAA area and perimeter well correlated with the actual device selection parameters during the procedure. The overestimation of the maximum diameter determined based on cMRI to the measurements based on XR and TEE indicates that the XR and TEE angulation was likely not optimally chosen to assess the maximum diameter as previously reported for measurements based on computer tomography (5, 11). The angulation prediction based on cMRI showed high potential of saving radiation, contrast agent, and interventional time.Acknowledgements

The project on which this report is based was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research under the funding code 13GW0372C. Responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors.References

1. Collado FMS, Lama von Buchwald CM, Anderson CK, Madan N, Suradi HS, Huang HD et al. Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion for Stroke Prevention in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 2021; 10(21):e022274.

2. Gloekler S, Saw J, Koskinas KC, Kleinecke C, Jung W, Nietlispach F et al. Left atrial appendage closure for prevention of death, stroke, and bleeding in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 2017; 249:234–46.

3. Holmes DR, Kar S, Price MJ, Whisenant B, Sievert H, Doshi SK et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2014; 64(1):1–12.

4. Bai W, Chen Z, Tang H, Wang H, Cheng W, Rao L. Assessment of the left atrial appendage structure and morphology: comparison of real-time three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography and computed tomography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017; 33(5):623–33.

5. Wang DD, Eng M, Kupsky D, Myers E, Forbes M, Rahman M et al. Application of 3-Dimensional Computed Tomographic Image Guidance to WATCHMAN Implantation and Impact on Early Operator Learning Curve: Single-Center Experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2016; 9(22):2329–40.

6. Nucifora G, Faletra FF, Regoli F, Pasotti E, Pedrazzini G, Moccetti T et al. Evaluation of the left atrial appendage with real-time 3-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography: implications for catheter-based left atrial appendage closure. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2011; 4(5):514–23.

7. Budge LP, Shaffer KM, Moorman JR, Lake DE, Ferguson JD, Mangrum JM. Analysis of in vivo left atrial appendage morphology in patients with atrial fibrillation: a direct comparison of transesophageal echocardiography, planar cardiac CT, and segmented three-dimensional cardiac CT. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2008; 23(2):87–93.

8. Al-Kassou B, Tzikas A, Stock F, Neikes F, Völz A, Omran H. A comparison of two-dimensional and real-time 3D transoesophageal echocardiography and angiography for assessing the left atrial appendage anatomy for sizing a left atrial appendage occlusion system: impact of volume loading. EuroIntervention 2017; 12(17):2083–91.

9. Goitein O, Fink N, Hay I, Di Segni E, Guetta V, Goitein D et al. Cardiac CT Angiography (CCTA) predicts left atrial appendage occluder device size and procedure outcome. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017; 33(5):739–47.

10. Homsi R, Meier-Schroers M, Gieseke J, Dabir D, Luetkens JA, Kuetting DL et al. 3D-Dixon MRI based volumetry of peri- and epicardial fat. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 32(2):291–9.

11. Rajwani A, Nelson AJ, Shirazi MG, Disney PJS, Teo KSL, Wong DTL et al. CT sizing for left atrial appendage closure is associated with favourable outcomes for procedural safety. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017; 18(12):1361–8.

Figures