4844

Tracking lipid and macromolecular changes in Ex-vivo hearts using NOEMTR and rNOE at 7T1Center for Advanced Metabolic Imaging in Precision Medicine (CAMIPM), Department of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Myocardium, Heart, CEST & MT

Two ex-vivo animal hearts were scanned at 7T to track lipid and macromolecular changes using NOEMTR and rNOE. Data was acquired on a fresh lamb heart and a healthy Yorkshire swine with an anteroseptal infarct by occlusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. After performing a multi-pool analysis, it is demonstrated that the NOEMTR and rNOE signal decreases in the infarcted region of the swine heart compared to the normal tissue and lamb heart.Introduction

Myocardial metabolic derangements in heart failure, obesity, and type 2 diabetes can result in lipid overstorage and lipotoxic injury to cardiomyocytes [1]. While 1H MRS has been used to detect intramyocardial triglyceride content in cardiovascular disease (CVD), it has limited spatial resolution, spatial coverage and sensitivity [2,3,4]. Recently, Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) MRI has been introduced as a high spatial resolution alternative to 1H MRS that can be used to study macromolecules such as lipids and proteins in the brain and calf muscle [5]. In a typical 1H homonuclear NOE imaging , the system is first perturbed at a specific group of resonances (e.g., aliphatic protons around 3.5 ppm up field from water) using a frequency selective low power saturation pulse lasting a few seconds. Subsequently, the saturated magnetization cross-relaxes with bulk water and leads to the NOE weighted MRI signal. This effect appears at 3.5 ppm up-field from bulk water, where most of the aliphatic protons from lipids and macromolecules resonate. NOEMTR is measured by subtracting the saturated signal from the unsaturated signal and normalizing the difference by the unsaturated signal. Since this cross-relaxation effect is also relayed through the chemical exchange, of labile protons on macromolecules with bulk water, the observed NOE is typically referred to as relayed NOE (rNOE). Since bound lipids have very short T2s, standard MRI is not suitable for measuring them. NOE is a highly sensitive technique to track lipid and macromolecular changes. In this study, we investigated the potential utility of NOEMTR as a technique to track lipid and macromolecular degeneration in infarcted tissue.Methods

An anteroseptal infarct was induced in a healthy Yorkshire swine by occlusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery for 90 minutes using a balloon catheter, followed by restoration of flow. The sacrifice of the animal occurred 9 days post-infarct and ex-vivo imaging was done 1-day post-sacrifice. As a control, data was also acquired from a fresh lamb heart prepared in PBS.Imaging parameters and post-processing:

All imaging was performed on a 7T whole body scanner (MAGNETOM Terra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a Nova Medical volume coil transmit/32-channel receive proton phased-array head coil. The 2D NOE acquisition parameters are: number of slices = 1, slice thickness = 8 mm, in-plane resolution = 1 x 1 mm2, matrix size = 240 x 180, gradient-echo readout TR = 3.5 s, TE = 1.79 ms, read-out flip angle = 4° , averages = 1, SHOT TR = 6000 ms, and a saturation pulse of B1,rms = 0.72 µT with saturation length of 3s [6]. The z-spectra was acquired at varying saturation offset frequencies from -7.5 to 7.5 ppm (relative to the water resonance) with a step size of 0.1 ppm. All imaging data was processed using an in-house written MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) routines. Z-spectra were normalized with reference signals (Δω = 100 ppm). Z-spectral fitting was performed using an in-house written program that utilizes the “lsqcurvefit” routine of MATLAB.

Results

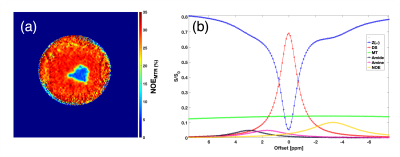

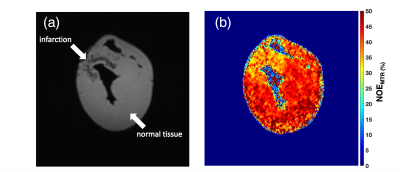

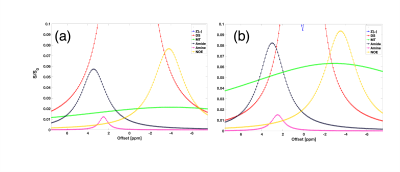

NOEMTR map of a fresh lamb heart tissue shows a homogenous contrast distribution (Figure 1a). The multi-pool Z-spectra demonstrates the feasibility of measuring rNOE in the lamb heart (Figure 1b). After performing the multi-pool separation, the rNOE signal is shown to contribute to ~10% of the total MTR signal from Figure 1b (line in yellow). Shown in Figure 2b is a lower NOEMTR signal in the infarcted region compared to the normal appearing tissue of a swine heart. This is most likey due to a change in lipid and macromolecule concentration post-infarction. The mean NOEMTR contrast is ~30% in the infarcted region compared to the healthy tissue (~45%). The multi-pool z-spectra (Figure 3) confirms this decrease by showing that the rNOE amplitude decreased by 1.5% from the normal appearing tissue to the infarcted region. The NOEMTR contrast from the lamb heart is lower than that of normal appearing region of the swine heart, which could be attributed to the difference in the basal level of macromolecules. Nonetheless, the contribution of rNOE to NOEMTR is similar in both tissues (~10%).Discussion and Conclusion

The multi-pool z-spectra and NOEMTR map both show that there is a drop in NOE signal (10%) in the infarcted region compared to the healthy tissue in the pig heart. This is most likely due to a degradation of lipids and macromolecules such as collagen during the myocardial infarction. It is the first time these molecular changes have been demonstrated using rNOE and NOEMTR. Therefore, rNOE and NOEMTR may serve as a biomarker to track lipidomic changes in CVD. Unlike, z-spectral asymmetry based measurements, the NOEMTR measurements can be performed rapidly under breath hold conditions to mitigate cardiac motion related issues. Furthermore, given higher magnitude of the signal and low amplitude saturation pulse, this method can be implemented at 3T with sufficient SNR. Thus, the translational potential of this approach to human studies is high and may overcome some of the limitations of 1H MRS study of cardiac steatosis. However, more work is needed to determine the amount and type of lipids and macromolecular contributions to the NOEMTR.Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under award number P41EB029460, the National Institute of Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R56AG062665 and R01AG071725, and by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under the award numbers R01HL137984 and F31HL158217.References

1. Machann, J., Häring, H., Schick, F., & Stumvoll, M. (2004). Intramyocellular lipids and insulin resistance. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism, 6(4), 239–248.

2. McGavock, J. M., Lingvay, I., Zib, I., Tillery, T., Salas, N., Unger, R., Levine, B. D., Raskin, P., Victor, R. G., & Szczepaniak, L. S. (2007). Cardiac steatosis in diabetes mellitus: a 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Circulation, 116(10), 1170–1175.

3. Lundbom J, Hakkarainen A, Sirén R, Nieminen MS, Taskinen MR, Lundbom N, Lauerma K. Cardiac steatosis and left ventricular function in men with metabolic syndrome. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013 Nov 14;15(1):103

4. Reingold, J. S., McGavock, J. M., Kaka, S., Tillery, T., Victor, R. G., & Szczepaniak, L. S. (2005). Determination of triglyceride in the human myocardium by magnetic resonance spectroscopy: reproducibility and sensitivity of the method. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism, 289(5), E935–E939.

5. Jones, C. K., Huang, A., Xu, J., Edden, R. A., Schär, M., Hua, J., Oskolkov, N., Zacà, D., Zhou, J., McMahon, M. T., Pillai, J. J., & van Zijl, P. C. (2013). Nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOE) imaging in the human brain at 7T. NeuroImage, 77, 114–124.

6. Cai, K., Haris, M., Singh, A. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of glutamate. Nat Med 18, 302–306 (2012).

Figures