4803

Radial vs. Spiral – A Comparison of Stack-of-stars and Stack-of-spirals Spatial Encoding Schemes in Multiparametric Body MRI with QTI1GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany, 2GE Healthcare, Madrid, Spain, 3IRCCS Stella Maris, Pisa, Italy, 4Technische Hochschule Ingolstadt, Ingolstadt, Germany, 5Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: MR Fingerprinting/Synthetic MR, Data Acquisition

Highly accelerated multiparametric MRI techniques are more and more demonstrating their diagnostic potential. To achieve short scan times, these techniques rely on non-Cartesian (under-) sampling. Initially developed for MRI applications in the brain, these sequences are now also applied in body MRI. In this work, we present a phantom and in vivo study to demonstrate and evaluate the strengths and pitfalls of the two most common non-Cartesian – spiral and radial – sampling schemes for the application of rapid, free-breathing 3D T1, T2 and proton density (PD) mapping with quantitative transient-state imaging (QTI) in the prostate gland.

Introduction

Fully quantitative MRI offers comprehensive diagnostic insights that go beyond solely qualitative structural imaging. Over the recent years, novel multiparametric MRI techniques1–4 have proven their potential to make quantitative MRI fast and robust enough for application in routine clinical workflows. To achieve clinically feasible scan times, these techniques often take advantage of non-Cartesian (under-) sampling schemes and/or measure transient-state signal evolutions instead of relying on lengthy steady-state acquisitions.Mostly demonstrated for neuro applications, these sequences are now also more and more entering the field of body MRI that poses additional challenges due to respiratory and bowel motion, B0 inhomogeneities and signal interference of water and lipid tissue components.

In this work, we present a phantom and in vivo study to demonstrate and evaluate the strengths and difficulties of the two most common non-Cartesian sampling schemes, i.e. spiral and radial trajectories. We take rapid, free-breathing 3D T1, T2 and proton density (PD) mapping with quantitative transient-state imaging (QTI) in the prostate gland as an example of application.

Methods

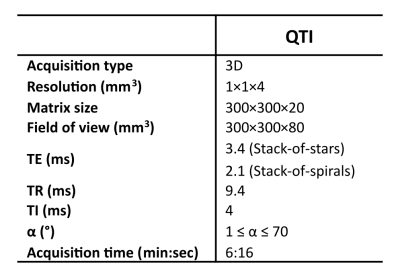

We implemented and optimized a Stack-of-stars and a Stack-of-spirals variant of QTI (Fig. 1b+c) using the MNS Research Pack (GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany) - a versatile toolkit for pulse and gradient waveform design and implementation. The QTI flip angle train (Fig. 1a) that is applied after an initial inversion pulse, comprises a sequence of 1000 RF excitations optimized using T1 and T2 Cramér-Rao bounds as a cost function5.As Figs. 1b+c illustrate, the segmented 3D QTI readout combines Cartesian phase-encoding along the logical z direction and radial or spiral in-plane sampling where radial spokes and variable density spirals are rotated with tiny golden angle and golden angle increments, respectively.

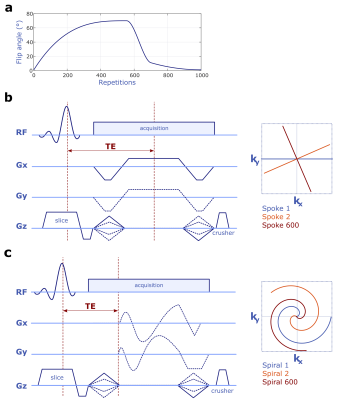

The two QTI variants were designed such that the scan parameters (Tab. 1) are identical except for a longer TE (to center of k-space) for the full-spoke radial trajectory.

QTI raw data was reconstructed via SVD-compression6, Cartesian re-gridding, 3D FFT, adaptive coil combination7 and orthogonal matching pursuit to simulated signals based on Extended Phase Graphs8. We intentionally omitted more advanced reconstruction approaches to illustrate how the two sampling schemes combined with the transient-state acquisition impact the parameter mapping result9 and to enable a fast online reconstruction directly on the MR scanner.

For in vitro evaluation, spiral and radial QTI datasets of the NIST phantom (QualibreMD, Boulder, CO) were acquired with an 8-channel head coil (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). We also performed an in vivo scan of a healthy volunteer using the AIR anterior coil and the GEM posterior array coil on a 3T Signa Premier whole-body MRI scanner (both GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) in compliance with the local ethical approvals.

Results and Discussion

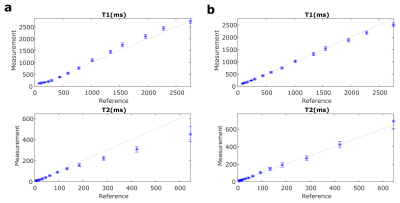

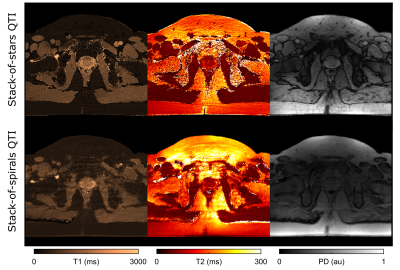

From the phantom study (Fig. 2), we find that for both QTI implementations T1 values agree well with the provided reference values. While spiral QTI achieves better correspondence with the reference for T2>200ms, both variants agree well with the reference for lower T2 ranges9.In terms of image quality, the core differences of the two readouts are apparent in Fig. 3: Spiral parameter maps appear smoother, while the radial counterpart exhibits some streak artifacts most prominently seen in PD.

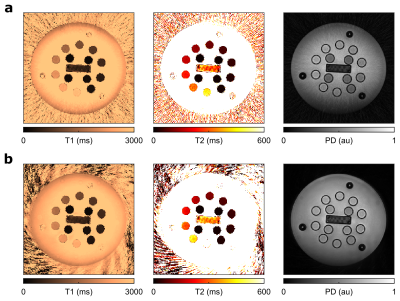

In vivo evaluation (Fig. 4) demonstrates that for both sampling variants we achieve clinically relevant image quality and motion robustness, whilst staying within the time constraints of routine clinical MRI (scan time=6:16min). Quantitatively, T1 and T2 parameter estimates are within reported T1 and T2 ranges in the prostate gland10–12.

Despite the overall good agreement between the two trajectories, their fundamental differences are clearly visible in vivo. In addition to the effects observed in the phantom scans, respiratory and bowel motion as well as B0 inhomogeneities and the interference of water and lipids are affecting the acquisition.

Again, spiral QTI maps are more sensitive to off-resonance blurring than the radial results. In case of radial QTI, we observe artificially low PD around the organs. This black boundary artifact at water-fat interfaces is particularly enhanced as TE is close to the out-of-phase condition (TE=3.4ms, TEOP= 3.3ms). Although spiral QTI is less affected by this phenomenon as TE is close to the in-phase condition (TE=2.1ms, TEIP=2.2ms), it seems that this variant is more sensitive to motion-induced blurring instead.

We observe higher SNR in bone structures in case of the spiral QTI variant. We anticipate that this is due to the shorter TE that is more beneficial to capture the fast-decaying bone signal. For prostate MRI, however, this is of minor importance.

Following this first evaluation, we plan to acquire more in vivo datasets to get deeper insights into how the two QTI variants compare, e.g., in a larger variety of breathing patterns and clinical pictures. It is also subject to future work to extend this study to other anatomies and field strengths.

Conclusion

We highlight the core differences of the two most common non-Cartesian – radial and spiral – trajectories for 3D multiparameter mapping with QTI in the prostate. Using the application of body MRI with respiratory and bowel motion, B0 inhomogeneities and interfering water and lipid components, we demonstrate the benefits and challenges when aiming for fast and robust multiparametric MRI.Acknowledgements

This project receives financial funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 952172.References

1. Warntjes JBM, Leinhard OD, West J, et al. Rapid magnetic resonance quantification on the brain: Optimization for clinical usage. Magn. Reson. Med. 2008;60(2):320–329.

2. Ma D, Gulani V, Seiberlich N, et al. Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting. Nature. 2013;495(7440):187–192.

3. Christodoulou AG, Shaw JL, Nguyen C, et al. Magnetic resonance multitasking for motion-resolved quantitative cardiovascular imaging. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018;2(4):215–226.

4. Gómez PA, Cencini M, Golbabaee M, et al. Rapid three-dimensional multiparametric MRI with quantitative transient-state imaging. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):13769.

5. Schulte RF, Pirkl CM, Garcia-Polo P, et al. Quantitative Parameter Mapping of Prostate using Stack-of-Stars and QTI Encoding. In: Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 30. London, United Kingdom; 2022.

6. McGivney DF, Pierre E, Ma D, et al. SVD compression for magnetic resonance fingerprinting in the time domain. IEEE TMI. 2014;33:2311–2322.

7. Walsh DO, Gmitro AF, Marcellin MW. Adaptive reconstruction of phased array MR imagery. Magn. Reson. Med. 2000;43(5):682–690.

8. Weigel M. Extended phase graphs: dephasing, RF pulses, and echoes - pure and simple. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI. 2015;41(2):266–295.

9. Stolk CC, Sbrizzi A. Understanding the Combined Effect of $k$ -Space Undersampling and Transient States Excitation in MR Fingerprinting Reconstructions. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2019;38(10):2445–2455.

10. Han D, Choi MH, Lee YJ, et al. Feasibility of Novel Three-Dimensional Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting of the Prostate Gland: Phantom and Clinical Studies. Korean J. Radiol. 2021;22(8):1332–1340.

11. Yu AC, Badve C, Ponsky LE, et al. Development of a Combined MR Fingerprinting and Diffusion Examination for Prostate Cancer. Radiology. 2017;283(3):729–738.

12. Baumann M, Keupp J, Mazurkewitz P, et al. Towards A Clinical Prostate MR Fingerprinting Protocol. In: Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 30. London, United Kingdom; 2022.

Figures

Figure 1 Variable flip angle RF excitation scheme optimized based on T1 and T2 Cramér-Rao bounds (a). Sequence diagrams of the proposed Stack-of-stars (b) and Stack-of-spirals (c) QTI schemes.

Figure 2 Quantitative analysis of Stack-of-stars (a) and Stack-of-spirals (b) QTI in the NIST phantom. Mean T1 and T2 values with the respective standard deviation obtained for each vial are compared to the provided reference values. The dashed lines indicate perfect agreement between QTI and the reference values.

Figure 3 Axial views of T1, T2 and PD mapping results with Stack-of-stars (a) and Stack-of-spirals (b) QTI in the NIST phantom.

Figure 4 Representative axial slice of QTI-based T1, T2 and PD maps with Stack-of-Stars (top) and Stack-of-Spirals (bottom) readout in a healthy volunteer.