4784

USING DEEP LEARNING WITH AN ACTIVE LEARNING APPROACH TO CORRECT WATER-FAT MIS-LABELING IN MR THORACIC SPINE IMAGES1Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Artifacts, Spinal Cord

Upon investigating a dataset of 804 studies for spinal fractures from two major vendors, the authors observed that 11% of the water-fat images in the studies are mis-labelled. This motivated the development of an automated algorithm to correct the mis-labelling. We used a 2D CNN based deep learning model to classify the images correctly with the aim of reducing error and fatigue in clinical diagnosis caused by such mis-labeling, as well as providing correct labels for further AI workflow. We also demonstrated the use of active learning in this problem by achieving the same test-error with fewer labels than using the entire training data.INTRODUCTION

Separation of water and fat from MRI scans is useful in the clinical diagnosis of edema in spinal MRI studies. Some of the methods used by major vendors include variations of the two-point Dixon method1 or the IDEAL method2. A typical Sagittal DIXON T2 scan would produce a set of water images and a set of fat images. We observed from a sample of 804 scans of the thoracic spinal cord that 11.1% of the set of water & fat images were mis-labelled (water as fat, fat as water) in the series description of the DICOM headers. Each image in the set of water/fat images has the same label. This presents disruptions for the physicians' workflow when viewing the images for diagnosis and complicates subsequent AI workflow involving use of water-fat images e.g. detection of compression fractures. Hence, in this retrospective study we used a deep-learning based classifier to correctly re-label water-fat images in Spinal MRI.METHODS

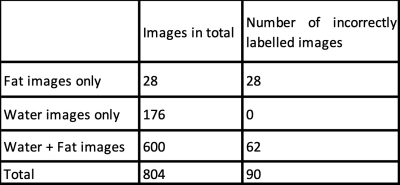

This study was reviewed by our Institutional Review Board and given a waiver. We present the statistics of incorrectly labelled water-fat images in Table 1. We found missing set of fat or water images in 25.3% of the scans. Among the studies with missing fat/water images, the set of fat images were always mis-labelled as water, while the set of water images were always correctly labelled. Studies involving both water and fat images had 10.3% rate in which the fat and water labels are incorrect.Ground truth labelling: We labelled 804 images by viewing the middle sagittal image of the set of water and fat images.

MODEL, TRAINING AND METRICS

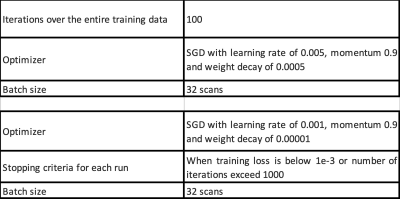

The algorithm contains the following stepsStep 1: Resize each image in the set of water/fat input images to 224*224 and rescale pixel values to (-1,1).

Step 2: Partition the studies into a training set of 400 scans and a test set of 404 scans.

Step 3: Each image is used for training the 2D model, with the training parameters given in Table 2. We used the EfficientNet-B03 model pretrained on ImageNet for training.

Step 4: During testing, we averaged the probability scores from each image in the set of water/fat images to get a score for the scan. If the scan had one set of fat/water images, then it was labelled as water or fat based on a score threshold of 0.5. If both sets of fat/water images were in the scan, then the one with lower probability of being fat was labelled as water.

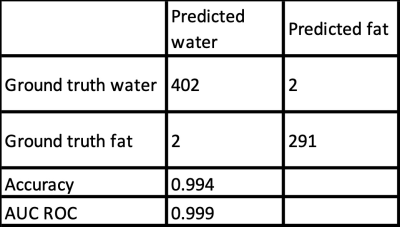

Evaluation Metrics: Since the training and test sets were balanced, we used the accuracy score to measure the performance of the algorithm.

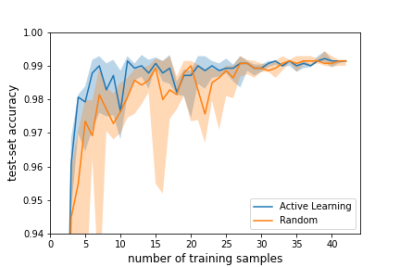

Active Learning: Curating and labelling data from PAC servers for AI training is a time-consuming process. Hence, we propose to minimize the number of samples to be labelled using Active learning4. This process is demonstrated below

Step 1: We started training with 2 scans chosen randomly from the 400 scans in the training set. This achieved an accuracy of 0.85.

Step 2: We evaluated the score of a scan as follows. The output of the EfficientNetB0 model was converted to a probability score. If the scan had one set of water/fat images, the score of the scan was the absolute difference of the average probability of the images in the set of water/fat images from 0.5. If the scan contained both water and fat images, we took the minimum of the score of both classes as the score of the scan.

Step 3: We added one scan to the set of training examples with the minimum score as computed from Step 2. The model was re-trained with the new training set starting from weights of the last trained model.

Step 4: We repeated this process to add 40 new scans with iterative re-training.

We show the accuracy of the above strategy as compared to the case where we added samples randomly one at a time from the remaining training examples in Figure 1. We observe that active learning achieved optimal test-set accuracy earlier than the random strategy.

RESULTS

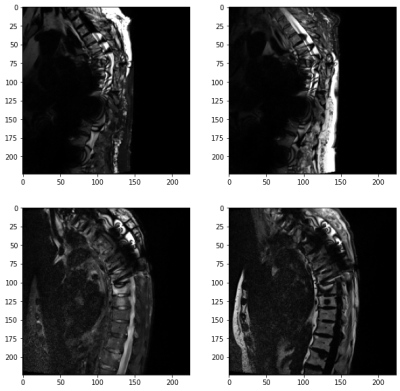

The results of our algorithm on the test-set are shown in Table 3. The accuracy in the test set was over 99%. We observed that our model failed in two out of the 404 scans, where both had local fat-water swaps and metal artifacts. These scans are shown in Figure 2.DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Our deep learning model was able to successfully resolve fat and water images in over 99% of the scans, correction over 90% of the scans with mis-labelling. Since water-fat separated images are widely used in clinical practice, our algorithm may help reduce errors and fatigue in clinical diagnosis. This algorithm may also be used to reduce error in further AI pipeline using water-fat classes as input, e.g. for spinal fracture detection. We believe similar algorithms can be developed for MR studies of other locations such as head and neck. We also demonstrated the effectiveness of an active learning approach to use fewer samples for training, to facilitate the practical implementation of such an algorithm. Exploring the effectiveness of active learning for larger unlabeled data sets will be a topic of future research.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] Dixon, W. Thomas. “Simple proton spectroscopic imaging.” Radiology 153, no. 1 (1984): 189-194.

[2] Reeder, Scott B., Angel R. Pineda, Zhifei Wen, Ann Shimakawa, Huanzhou Yu, Jean H. Brittain, Garry E. Gold, Christopher H. Beaulieu, and Norbert J. Pelc. “Iterative decomposition of water and fat with echo asymmetry and least‐squares estimation (IDEAL): application with fast spin‐echo imaging.” Magn. Reson Med 54(3) (2005): 636-644.

[3] Tan, Mingxing, and Quoc Le. “Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks.” In International conference on machine learning, pp. 6105-6114. PMLR, 2019.

[4] Settles, Burr. "Active learning." Synthesis lectures on artificial intelligence and machine learning 6, no. 1 (2012): 1-114.

Figures