4765

Cerebral haemodynamic correlates of altered consciousness states induced by High-ventilation breathwork1Radiology, Leiden Univeristy Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands, 2Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Brighton, United Kingdom, 3Department of Psychiatry, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, United States, 4Brighton BodyTalk, Brighton, United Kingdom, 5Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Perfusion

‘Breathwork’ is pursued by a rapidly growing set of adherents, anecdotally because it evokes psychedelic experiences that positively effect mood. We measured regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) during high-ventilation breathwork (HVB) in healthy participants. Furthermore, we assessed the relationship between rCBF changes and subjective experience, focusing on altered state of consciousness. HVB was associated with substantial global reduction in CBF. Moreover, reduction in rCBF in anterior cingulate and insular cortices scaled with intensity of subjective experiences. These brain regions are implicated in supporting interoceptive control underlying affective regulation. Understanding the neural effects of HVB can inform new clinical applications.Introduction

The interest in the therapeutic potential of various breathwork practices is steadily growing. Practices such as holotropic or conscious-connected breathwork employ fast-paced breathing techniques whereby practitioners may hyperventilate for prolonged periods1. The reported subjective effects of such “High-ventilation breathwork (HVB)” practices include profound changes in emotions, thoughts and self-experience resembling some of the altered state of consciousness (ASC) induced by serotonergic agonists such as psilocybin or LSD2,3. The exact mechanisms underlying these effects of HVBs are unknown. Voluntary hyperventilation is well known to induce hypocapnia and respiratory alkalosis, likely leading to complex alterations in cerebral haemodynamics that can directly impact neuronal metabolism and function4. We employed quantitative assessments of regional cerebral blood flow using pseudo-continuous arterial spin labelling (pcASL) to explore the cerebral haemodynamic correlates of HVB’s subjective effects.Methods

Physically and mentally healthy participants, with over 6-months experience in regular HVB practice, were recruited to the study. Participants underwent MRI scans on a Siemens Prisma 3T scanner equipped with a 32-channel head coil. End-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) data were acquired during the scans through a nasal cannula connected to a capnograph. Participants were guided, through pre-recorded audio instructions delivered during the scan, to breathe at normal rate (BASE phase) for 20 minutes and then to hyperventilate for the following 25 minutes (HVB phase). MR acquisitions for the HVB phase were started once EtCO2 was stable at levels below 20mmHg. Experimental settings and instructions reproduced the usual experience of therapeutic HVB as regularly practised by the participants. This also included listening to evocative ambient music whose tempo progressively increased from BASE to end of HVB. PcASL data were acquired at BASE, and twice during HVB, i.e., immediately after starting HVB (START HVB), and after 6 minutes of uninterrupted HVB (SUSTAINED HVB). The scanning protocol for each pcASL acquisition included post labelling delay= 1800ms, labelling duration = 2000 ms, TR = 5000ms, TE = 14ms, in-plane resolution = 3.5 x 3.5 mm2 and slice thickness = 6mm. High-resolution T1-weighted volume (MPRAGE) was also acquired. Regional CBF maps were computed5 and processed to obtain partial volume corrected6, normalised maps in MNI space. Differences between each of the HVB phases and BASE were tested using paired-sample t-tests in SPM12, and voxelwise maps of delta CBF were computed. Subjective measures were assessed 30 minutes post-MRI scans using the ASC domain of the 5-Dimensional ASC Rating Scale7. The analysis of correlations of delta CBF to ASC measures were performed in SPM12.Results

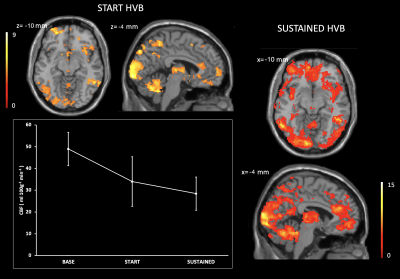

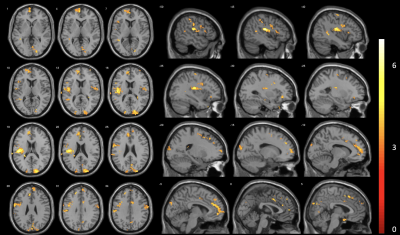

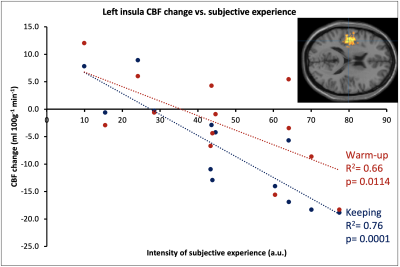

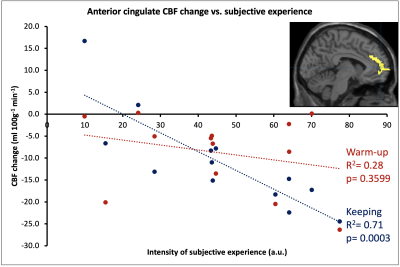

The HVB experiment was well tolerated by all participants. After assessment of image quality, 13 datasets (mean age 43.7±11.9; 7 female) were deemed of sufficient quality. Symmetrical CBF reductions were visible during START HVB, relative to BASE, and became widespread through SUSTAINED HVB (Figure 1). The proportion of GM with reduced CBF was 12.4% of global GM volume during START HVB and 28.8% during SUSTAINED HVB. Global CBF was reduced by 30.6% during START HVB (34.0±11.4 ml 100g-1 min-1) and 41.9% during SUSTAINED HVB (28.4±7.6 ml 100g-1 min-1) relative to BASE (49.0±7.6 ml 100g-1 min-1).We identified regional clusters of significant correlations in left dorsal posterior insular and anterior cingulate cortices (Figure 2). Within the left insula, ASC scores were associated with both the delta CBF during START HVB and SUSTAINED HVB. Within the anterior cingulate, ASC scores correlated with the delta CBF during SUSTAINED HVB only (Figures 3 and 4).Discussion

We observed a robust and substantial time-dependent decrease in CBF across the whole brain in response to HVB. The intensity of subjective reports of ASC was associated with rCBF reductions in areas critically involved in conscious and affective representations of internal states, namely the dorsal mid and posterior insula and the anterior cingulate cortex8,9.The dorsal posterior insula, integrating autonomic and interoceptive signals from chemosensors and cardio-respiratory afferents, is interconnected to the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which is implicated in attentional and behavioural aspects of affective regulation and in efferent control of autonomic state8,9. Conjoint insula-cingulate activity, integrating higher-order cortical functions with interoceptive representation and autonomic control, is purported to have a key role in forming whole-organism, representations of self, by integrating interoceptive signals with autonomic arousal responses10. Prolonged hyperventilation, through hypocapnia, alkalisation of CNS tissue, and reduced perfusion to central nervous system (CNS) impacts the function of neurons through multiple pH- and O2- dependent mechanisms leading to reduced GABAergic inhibitory drive, hyperexcitability of excitatory neurons’ and ultimately CNS tissue’s metabolic distress4. Hyperventilation acts as a neurometabolic challenge, to which specific interneuron populations responsible for the stabilisation of excitatory networks, are exquisitely vulnerable11. It is plausible that sustained HVB induces the progressive disruption of insular - cingulate interactions, compromising central aspects of self-representation and ultimately leading to altered - albeit brief and reversible - states of consciousness.Conclusion

We observed ASC-induced by HBV to correlate with reduced insular and cingulate perfusion in a time-dependent fashion. These findings point to a plausible mechanism underlying the acute subjective effects of HVB, a practice that has attracted interest for therapeutic applications. Precise understanding of the mechanistic effects of HVB at CNS level, might inform personalised therapeutic applications studies and is crucial to clarify its profile of both clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Rhinewine, J. P., & Williams, O. J. (2007). Holotropic breathwork: The potential role of a prolonged, voluntary hyperventilation procedure as an adjunct to psychotherapy. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 13(7), 771–776. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2006.6203

2. Grof, S. & Grof, C. (2010). Holotropic breathwork, State University of New York.

3. Uthaug, M. V., Mason, N. L., Havenith, M. N., Vancura, M., & Ramaekers, J. G. (2022). An experience with holotropic breathwork is associated with improvement in non-judgement and satisfaction with life while reducing symptoms of stress in a Czech-speaking population. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 5(3), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2021.00193

4. Curley, G., Kavanagh, B. P., & Laffey, J. G. (2010). Hypocapnia and the injured brain: More harm than benefit. Critical Care Medicine, 38(5), 1348–1359. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0b013e3181d8cf2b

5. Alsop, D.C. et al. (2014) “Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: A consensus of the ISMRM Perfusion Study Group and the European Consortium for ASL in Dementia,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 73(1), pp. 102–116. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.25197.

6. Asllani, I., Borogovac, A., & Brown, T. R. (2008). Regression algorithm correcting for partial volume effects in arterial spin labeling MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 60(6), 1362–1371. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.21670

7. Dittrich, A, Lamparter, D , Maurer , M (2010) 5D-ASC: Questionnaire for the assessment of altered states of consciousness. A short introduction. Zurich, Switzerland.

8. Nord, C. L., Lawson, R. P., & Dalgleish, T. (2021). Disrupted dorsal mid-insula activation during interoception across psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(8), 761–770. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20091340

9. Kuehn, E., Mueller, K., Lohmann, G., & Schuetz-Bosbach, S. (2015). Interoceptive awareness changes the posterior insula functional connectivity profile. Brain Structure and Function, 221(3), 1555–1571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-015-0989-8

10. Colasanti, A., & Critchley, H.D., (2021). Primordial Emotions, Neural Substrates, and Sentience: Affective Neuroscience Relevant to Psychiatric Practice Journal of Consciousness Studies, Volume 28, Numbers 7-8, 2021, pp. 154-173(20).

11. Pinna, A., & Colasanti, A. (2021). The neurometabolic basis of mood instability: The Parvalbumin Interneuron Link—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.689473

Figures