4764

The selfish brain – Unaltered brain temperature in the acute state of Anorexia Nervosa1Translational Developmental Neuroscience Section, Division of Psychological and Social Medicine and Developmental Neuroscience, Faculty of Medicine, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany, Dresden, Germany, 2Center for Clinical Spectroscopy, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA USA 02115, Boston, MA, United States, 3Institute of Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, Technical University, Dresden, Dresden, Germany, Dresden, Germany, 4Eating Disorder Research and Treatment Center, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany, Dresden, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Spectroscopy, Brain temperature

In anorexia nervosa (AN) restrictive food intake leads to a slowed metabolism. Brain temperature, can provide information about brain metabolism. Difference between Magnetic Resonance Spectrum peaks (ΔH20-NAA) provide a proxy for brain temperature in 30 AN and 30 healthy control (HC) participants. We found no group differences in brain temperature between AN/HC. Further, we report no group differences in brain temperature between a subgroup of the AN participants with the lowest BMI/body temperature compared to a subsample with higher BMI/body temperature. The results suggest a prioritization of brain metabolism in AN in line with the selfish brain hypothesis.Background

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious psychiatric disorder characterized by severe self-restriction of food intake leading to undernutrition 1. Although primarily considered a psychiatric disorder, the acute state of AN is associated with severe physiological changes and alterations in the body's metabolism to adapt to a state of energy deprivation 2. While the effects of a slowed metabolism in acute AN can lead to severe hypothermia with body temperatures below 36°C 3,4, the effects on brain temperature have not yet been investigated.Magnetic resonance spectroscopy can be used as a noninvasive method to measure the in vivo temperature of the brain 5. The aim of this report is to investigate whether brain temperature in acutely underweight patients remains unchanged despite lower body temperature. We base our hypothesis on the assumption that in times of food deprivation, the brain “selfishly” 6 competes with the body to meet its energy needs (brain-pull mechanism) 7.

Methods

We collected magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) data of 30 participants with acute AN (acAN, age mean = 16.1 (sd = 2.2)) and 30 age matched healthy controls (HC, age mean = 16.2 (sd = 1.8)). The study was conducted at a 3T Magnetom Prisma Scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with a 32-channel head coil between 2 p.m. and 4 p.m.The 2D multivoxel 1H MRS CSI measurement was acquired with a SIEMENS CSI spin echo sequence (TR 1700 ms, TE 30 ms) with 4 averages. A second acquisition without water suppression was measured for eddy current correction. A volume of interest (VOI) was chosen right above the corpus callosum and angled so it included a maximum volume for later analyses. Vendor provided automated voxel positioning was used to position the VOI (SIEMENS auto-align) 8. Siemens GRE 3D B0 shim routine and manually adjustment was used to achieve a mean shim value of 17.1 (SD=1.7).

We used LCModel for metabolite quantification (http://s-provencher.com/lcmodel.shtml)(REF). After exclusion of all outer voxels to avoid chemical shift displacement artefacts, the reaming voxels (matrix of 6x6) were quality controlled (voxels with FWHM higher than 0.1 ppm and/or a signal-to-noise ratio of less than 3 were excluded) and visually inspected for artifacts.

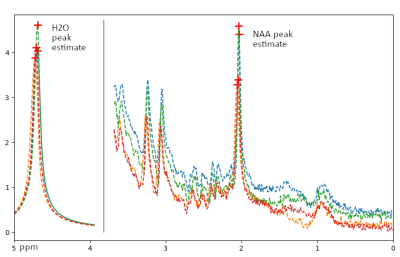

We used an in-house python script and the PeakUtils python library ( https://peakutils.readthedocs.io) to detect the temperature independent peak of N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) and the temperature dependent water peak (H20) in each voxel. Next, we calculated the differences (ΔH20-NAA) between the two peaks (See exemplary Figure 1). A larger difference correlates with a lower temperature in the respective voxel 5.

We applied an independent t test to compare brain temperature in acAN to HCs. We assumed equal brain temperature in acAN and HC groups.

Further, we investigated our hypothesis that even in cases of extremely low weight and low body temperature the brain temperature would stay unchanged. We used a median split in the acAN group and compared half of the acAN participants with the lowest BMI standard deviation scores (BMI-SDS 9 with the half with higher BMI-SDS. The same procedure was used to compare brain temperature of half of the acAN with the lowest body temperature (measured orally at admission) to the corresponding half with higher body temperature.

Results

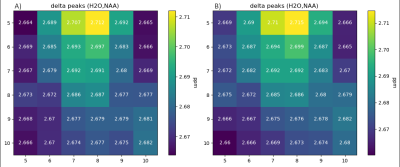

As expected, acAN showed no significant indication for a greater ΔH20-NAA (lower brain temperature) compared to HCs (mean ΔH20-NAA (acAN = 2.68|HC = 2.68), t = -0.14, p = 0.89). Voxel wise analysis did not provide evidence for regional differences between acAN and HCs (Figure 2). Furthermore, those acAN with the lowest BMI-SDS at the time of research (n= 15, mean BMI-SDS = -4.40) showed no significantly greater ΔH20-NAA (t = -0.96, p = 0.34) compared to those with higher BMI-SDS (n= 15, mean BMI-SDS = -2.82). Half of the acAN with the lowest body temperature (n= 11, mean body temperature = 35.81°C) showed no significantly greater ΔH20-NAA (t = 0.52, p = 0.61) compared to those with higher BMI-SDS (n= 11, mean body temperature = 36.72°C).Conclusions

Our findings show no group differences in ΔH20-NAA between acAN and HC even though the core body temperature in our acAN cohort was severely lower than previously reported body temperature average in comparable healthy age groups 10. The results, in line with the selfish brain hypothesis 6,7, suggest a prioritization of normal brain temperature/metabolism in a system with limited energy and under extreme conditions.Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge funding from the following grants: German Research Foundation (S.E., grant numbers SFB 940/2, EH 367/5-1, EH 367/7-1), the Swiss Anorexia Nervosa Foundation (S.E.), and the B. Braun Foundation (S.E.).References

1. Gibson D, Workman C, Mehler PS. Medical Complications of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2019;42:263–274 doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2019.01.009.

2. Duriez P, Mastellari T, Viltart O, Gorwood P. Clinical meaning of body temperatures in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review 2022;30:124–134.

3. Chudecka M, Lubkowska A. Thermal imaging of body surface temperature distribution in women with anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review 2016;24:57–61.

4. Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp 2002;17:143–155 doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062.

5. Rieke V. MR thermometry. Interventional Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2011:271–288.

6. Peters A, Schweiger U, Pellerin L, et al. The selfish brain: competition for energy resources. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2004;28:143–180.

. Hitze B, Hubold C, Van Dyken R, et al. How the selfish brain organizes its supply and demand. Frontiers in neuroenergetics 2010;2:7.

8. Dou W, Speck O, Benner T, et al. Automatic voxel positioning for MRS at 7 T. Magn Reson Mater Phy 2015;28:259–270 doi: 10.1007/s10334-014-0469-9.

9. Hemmelmann C, Brose S, Vens M, Hebebrand J, Ziegler A. Perzentilen des Body-Mass-Index auch für 18- bis 80-Jährige? Daten der Nationalen Verzehrsstudie II. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2010;135:848–852 doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1253666.

10. Geneva II, Cuzzo B, Fazili T, Javaid W. Normal body temperature: a systematic review. In: Open forum infectious diseases. Vol. 6. Oxford University Press US; 2019. p. ofz032.