4757

Disrupted causal connectivity anchored on cerebellum in first-episode medication-naive schizophrenia and restoration after treatment1Huaxi MR Research Center (HMRRC), Department of Radiology, Functional and Molecular Imaging Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, West China Hospital, Sichuan University., Chengdu, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Brain Connectivity

Cerebellar dysfunction appears to be a robust phenomenon in schizophrenia, and stimulation targeted at cerebellum can alleviate some symptoms. However, the causal information flow and longitudinal change of cerebrum-cerebellar connectivity were unclear, limiting the choice of precise stimulation strategies. Using Granger causality analysis, we found decreased excitatory inflow and increased inhibitory outflow were located on different cerebellar functional systems in first-episode schizophrenia and these gradually returned to normal in the context of clinical improvement with ongoing antipsychotic treatment. Our work potentially provides new information to facilitate precision medicine targeted at cerebellum.Introduction

Disrupted cerebellum-cerebral communication has been proposed resulting in psychotic symptoms and cognitive deficits, which is theorized as the “cognitive dysmetria” hypothesis[1]. To date, some functional connectivity studies repeatedly showed failures of cerebellum-cerebral communication on first-episode patients [2–7], chronic patients[8–11], and individuals at clinical or genetic risk of schizophrenia[2,5,11–14]. However, the cerebellar causal information inflow and outflow remain unclear. Moreover, cerebellar subunits exhibit diverse functional connectivity with cerebrum[15]. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to identify regional cerebellar causal effect disruptions in first-episode medication-naive schizophrenia and longitudinal changes with undergoing antipsychotic treatment.Methods

Subjects: The study included baseline clinical and neuroimaging data acquired from 180 first-episode patients (79males, mean age=24.2) and 161 demographically matched healthy controls (81males, mean age=25.4). The Structured Clinical Interview of DSM-IV was applied for the diagnosis of schizophrenia. The disease duration for all patients was less than 5 years. 54 of these patients followed up at one-year and 29 at two-year time points. During follow-ups, symptom severities were evaluated by the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) at each assessment point.Imaging acquisition and preprocessing: Data for all subjects at all time points were acquired on a 3T GE Signa EXCITE scanner located at the West China Hospital, Sichuan University. DPARSF (http://www.restfmri.net) 16 and SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) toolkits were used for MRI data pre-processing, involving removal of ten volumes, slice time correction, realignment, segmentation, normalization to the MNI space, and spatial smoothing at 4-mm FWHM. The images were further corrected for white matter and cerebrospinal fluid signals, and 24 head-motion parameters, and temporally filtered at 0.01–0.1 Hz. The global signal was not removed in the present study.

Granger causality analysis (GCA): The bivariate coefficient-based, first-order GCA was performed using the REST (http://www.restfmri.net) software package17,18. Each of the nine cerebellar systems was examined by whole-brain-to-seed and seed-to-whole-brain analyses. The whole-brain-to-seed analysis was used to estimate the driving effect (excitatory or inhibitory) from the other voxels of the whole brain to the seed (y2x map), whereas the seed-to-whole-brain analysis was applied to estimate the feedback effect (excitatory or inhibitory) from the seed to other voxels of the whole brain (x2y map). The y2x maps and x2y maps were further z-transformed.

Statistical analysis: Two-sample t-tests were applied to determine the causal connectivity disruption in untreated first-episode schizophrenia patients compared to healthy controls. To improve the statistical significance of the final result, a one-sample t-test for y2x maps of each cerebellar system was performed for both groups to determine regions which significantly different from zero (P < 0.05, FDR corrected). After false discovery rate (FDR) correction, nine “causal effect masks” were generated by integrating the paired result of the one-sample t-test of the two groups. Under each “causal effect mask”, the corresponding y2x maps of two groups were subjected to a two-sample t-test, followed by another FDR correction (P < 0.05, FDR corrected). The analysis process for the x2y maps was done the same as above. Further, the paired t-test between baseline and follow-up (one-year or two-year) GCA values of each region of interest was performed by using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, version 26.0). Finally, the correlations between the GCA value of each ROI and the PANSS scores were calculated for the patient group. The GCA value of each ROI at follow-up minus baseline was ΔGCA value. PANSS score of each domain at follow-up minus baseline were ΔPANSS score. The same linear regression analysis was used to test the associations between the ΔGCA value and ΔPANSS score.

Results

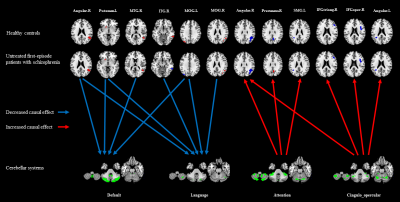

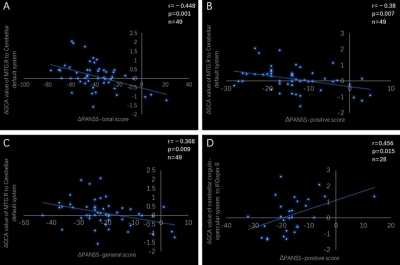

We observed decreased excitatory inflow from cerebral occipital, temporal, parietal lobes, and putamen to cerebellar default and language systems, whereas increased inhibitory outflow from cerebellar attention and cingulo-opercular systems to cerebral frontal, parietal lobes in untreated first-episode schizophrenia patients compared to healthy controls (Figure 1). At follow-up, all the causal effect inflow to cerebellum was increased and outflow from cerebellum was decreased with ongoing antipsychotic treatment, to be specific, the information from left middle occipital gyrus inflow to cerebellar default and language systems, from the cerebellar cingulo-opercular system outflow to left angular, from right middle temporal gyrus (MTG) inflow to cerebellar default system was most significantly restored to a normal level. The excitatory effect from the right MTG to cerebellar default system increase was related to the PANSS-total, PANSS-positive, PANSS-general remission, and the inhibitory effect from cerebellar cingulo-opercular system to right the opercular part of the right inferior frontal gyrus decrease was related the PANSS-positive remission (Figure 2).Conclusion

In sum, we found a breakdown of the cerebellum-cerebral connectivity during the acute phase of schizophrenia which was normalized in the context of clinical improvement, and different cerebellar systems express different causal effect disruption, suggesting that more targeted treatment strategies should be taken for different cerebellar systems.Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for their involvement in this study.References

1 Andreasen NC, Paradiso S, O'Leary DS. "Cognitive dysmetria" as an integrative theory of schizophrenia: a dysfunction in cortical-subcortical-cerebellar circuitry? Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(2):203-218.

2 Bang M, Park H-J, Pae C, et al. Aberrant cerebro-cerebellar functional connectivity and minimal self-disturbance in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis and with first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2018;202:138-140.

3 Guo W, Zhang F, Liu F, et al. Cerebellar abnormalities in first-episode, drug-naive schizophrenia at rest. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2018;276:73-79.

4 Lee K-H, Oh H, Suh J-HS, et al. Functional and Structural Connectivity of the Cerebellar Nuclei With the Striatum and Cerebral Cortex in First-Episode Psychosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;31(2):143-151.

5 Li Z, Huang J, Hung KSY, et al. Cerebellar hypoactivation is associated with impaired sensory integration in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2021;130(1):102-111.

6 Park SH, Kim T, Ha M, et al. Intrinsic cerebellar functional connectivity of social cognition and theory of mind in first-episode psychosis patients. NPJ Schizophr. 2021;7(1):59.

7 Xie YJ, Xi YB, Cui L-B, et al. Functional connectivity of cerebellar dentate nucleus and cognitive impairments in patients with drug-naive and first-episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2021;300:113937.

8 Clark SV, Tannahill A, Calhoun VD, Bernard JA, Bustillo J, Turner JA. Weaker Cerebellocortical Connectivity Within Sensorimotor and Executive Networks in Schizophrenia Compared to Healthy Controls: Relationships with Processing Speed. Brain Connect. 2020;10(9):490-503.

9 He H, Luo C, Luo Y, et al. Reduction in gray matter of cerebellum in schizophrenia and its influence on static and dynamic connectivity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40(2):517-528.

10 Shinn AK, Baker JT, Lewandowski KE, Öngür D, Cohen BM. Aberrant cerebellar connectivity in motor and association networks in schizophrenia. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9.

11 Wang H, Guo W, Liu F, et al. Patients with first-episode, drug-naive schizophrenia and subjects at ultra-high risk of psychosis shared increased cerebellar-default mode network connectivity at rest. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:26124.

12 Bernard JA, Dean DJ, Kent JS, et al. Cerebellar networks in individuals at ultra high-risk of psychosis: impact on postural sway and symptom severity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(8):4064-4078.

13 Cao H, Chén OY, Chung Y, et al. Cerebello-thalamo-cortical hyperconnectivity as a state-independent functional neural signature for psychosis prediction and characterization. Nature Communications. 2018;9(1):3836.

14 Cao H, Wei X, Hu N, et al. Cerebello-Thalamo-Cortical Hyperconnectivity Classifies Patients and Predicts Long-Term Treatment Outcome in First-Episode Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2021;89(9):S83-S83.

15 Ji JL, Diehl C, Schleifer C, et al. Schizophrenia Exhibits Bi-directional Brain-Wide Alterations in Cortico-Striato-Cerebellar Circuits. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991). 2019;29(11):4463-4487.

16 Chao-Gan Y, Yu-Feng Z. DPARSF: A MATLAB Toolbox for "Pipeline" Data Analysis of Resting-State fMRI. Frontiers In Systems Neuroscience. 2010;4:13.

17 Zang Z-X, Yan C-G, Dong Z-Y, Huang J, Zang Y-F. Granger causality analysis implementation on MATLAB: A graphic user interface toolkit for fMRI data processing. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2012;203(2):418-426.

18 Song X-W, Dong Z-Y, Long X-Y, et al. REST: a toolkit for resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging data processing. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25031.

Figures