4754

White and Grey Matter Microstructure Alterations in Early Psychosis and Schizophrenia1Department of Radiology, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland, 2University of Lausanne (UNIL), Lausanne, Switzerland, 3Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience, Department of Psychiatry, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland, 4General Psychiatry Service, Treatment and Early Intervention in Psychosis Program (TIPP-Lausanne), Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland, 5Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience and Service of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Microstructure, Schizophrenia, Neuroinflammation, Neurodegeneration, Microstructure, Diffusion, White Matter, Grey Matter

In schizophrenia, widespread brain abnormalities are commonly reported but not the microstructure alterations. Here, we investigate brain microstructure during early psychosis and schizophrenia using DKI (in GM & WM), a clinically feasible extension of DTI, and we apply the White Matter Tract Integrity – Watson (WMTI-W, WM only) model. In WM, extensive alterations, consistent with demyelination, were found in early psychosis, while transitioning to chronic schizophrenia, microstructure changes become region-specific as indicated by the two ROI-dependent trends of disease progression found in this cohort. GM showed increased diffusivities and decreased kurtosis, but not widespread as in WM.Introduction

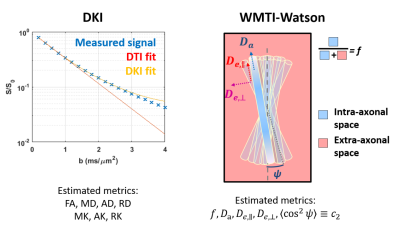

In schizophrenia, widespread brain abnormalities are often reported1-3, however little is known about the specific microstructure alterations and most previous studies focused on DTI changes4, reporting reduced fractional anisotropy5 (FA) and higher diffusivities. Here, we investigate potential changes in brain tissue microstructure during early psychosis and schizophrenia using diffusion kurtosis imaging6 (DKI, in both GM and WM), which is a clinically feasible extension of DTI that estimates complementary metrics of tissue heterogeneity and complexity. In the WM, we also apply the White Matter Tract Integrity – Watson7 biophysical model (WMTI-W), which outputs specific metrics of microstructure features, with fewer assumptions than NODDI8 (Fig.1).Methods

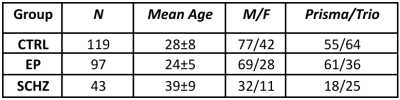

The relevant ethics committee approved the study. MRI: Data from 259 subjects (Table 1) were collected on two scanners (Siemens 3T Prisma and Trio), divided as N=119 healthy individuals (CTRL), N=97 early psychosis (EP, <5 years from first exceeding psychosis threshold) and N=43 chronic schizophrenic patients (SCHZ). An MPRAGE was acquired for anatomical reference (1-mm isotropic resolution). Whole-brain diffusion-weighted images were acquired using a PGSE-EPI sequence (TE/TR = 0.144/6.1 ms, 2-mm isotropic resolution, 15 b-values, range 0-8 ms/μm2, Cartesian q-space coverage totalling 129 (Trio, Prisma) or 257 (Trio) images). The preprocessing pipeline included MP-PCA denoising and Gibbs ringing, EPI distortion, eddy currents, and motion corrections. Diffusion and kurtosis tensors and scalar metrics (Fig.1) were estimated voxel-wise from data with b≤2.5 ms/μm2. Only in WM voxels, the WMTI-W model parameters were computed using an in-house Python script. Individual FA maps were registered to the Johns Hopkins University FA template and WM regions of interest (ROIs) were projected to individual space. GM was segmented in MPRAGE individual space using FastSurfer9, and the Desikan-Killiany-Tourville parcellation was projected to diffusion space. Each available diffusion metric was averaged per WM and GM ROI. Finally, all the estimated metrics of WM and GM were harmonized for scanner type via ComBat10. CTRLs were greedily matched with the clinical groups by age and scanner. Groups were compared using the Brunner-Munzel test, controlled for age and sex, and p-values were FDR-corrected.Results

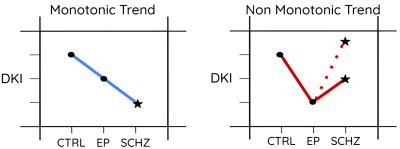

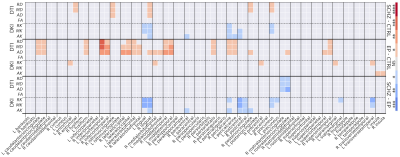

WM: Microstructure alterations were found in EP and SCHZ (Fig. 2). SCHZ vs CTRL (Fig.2, top-block): Higher diffusivity and lower kurtosis, consistent with structure loss, were found e.g. in the fornix (Fx) and corona radiata (CR) of SCHZ. Interestingly, a few ROIs (e.g. external capsule, EC) showed an opposite pattern of increased kurtosis in SCHZ vs CTRL. The WMTI model revealed primarily reduced axonal water fraction f and increased extra-axonal diffusivities, markers of reduced cellular density and demyelination. EP vs CTRL (Fig.2, mid-block): Differences were mainly marked by increased diffusivity and reduced kurtosis. Remarkably, differences in EP-CTRL were more widespread and significant than differences in SCHZ-CTRL. WMTI-W metrics revealed an increase in all compartment diffusivities and reduced f, supporting loss of structure. SCHZ vs EP (Fig.2, bottom-block): The most pronounced differences between SCHZ and EP were found in the external capsule (EC), where SCHZ subjects remarkably had a higher kurtosis, f and Da than EP. In contrast with this trend, other areas (e.g., CR) showed further reduced kurtosis in SCHZ vs EP, supporting sustained neurodegeneration. Overall, two ROI-dependent trends of disease progression from CTRL to EP and SCHZ could be identified (Fig.3): a monotonic trend of degeneration as in the Fx or CR; and a non-monotonic trend, where EP kurtosis was the lowest of all groups, as in the EC. GM: GM diffusion alterations appeared less prominent than WM differences. SCHZ vs CTRL (Fig.4, top-block): GM showed increased diffusivities and decreased kurtosis, but not as widespread as in WM. Decreased kurtosis, consistent with reduced neurite density, was found in the bilateral lingual gyrus and pericalcarine cortex. EP vs CTRL (Fig.4, mid-block): Higher GM diffusivities in EP were more widespread than for the SCHZ-CTRL comparison. Instead of a decrease in kurtosis (as found in SCHZ GM and EP WM), a weak yet significant increase in radial kurtosis was found in areas of the right cortex. Differences were present bilaterally in the insula. SCHZ vs EP (Fig.4, bottom-block): Most significant differences showed reduced kurtosis in the SCHZ compared to EP. Involved areas were the bilateral precuneus, lingual and postcentral gyrus.Discussion and conclusion

DMRI metrics revealed microstructure alterations in WM and GM. In WM, widespread alterations, consistent with demyelination, were found in EP subjects. This effect could be the result of oxidative stress caused by redox dysregulation, which alters the proliferation and differentiation of the oligodendrocytes precursor cells11-14 ending in the observed WM abnormalities. Going from EP to chronic SCHZ, microstructure changes become region-specific, with some WM ROIs exhibiting diffusion signatures of sustained degeneration, while others show a reversal of diffusion trends, which could suggest increased cellularity due to renewed inflammation or iron release reducing the extracellular T2 and thereby this compartment’s contribution to overall diffusion MRI signal. In the GM, EP vs CTRL differences were also more widespread than SCHZ vs CTRL. Generally, the decrease in DKI metrics was compatible with neurite loss due to disease chronicity. Future work will focus on linking brain region-specific WM and GM trajectories with complementary clinical and biological markers.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Center of Competence

in Research (NCCR) “SYNAPSY-The Synaptic Bases of Mental Diseases”

from the Swiss National Science Foundation (n°51AU40_125759 to

KQD&PC, 51NF40_158776 and 51NF40_ 185837).

TP and IJ are supported by SNSF Eccellenza grant PCEFP2_194260. PH is supported by SNSF grant 320030_197787.

References

[1] Kelly et al., Mol. Psychiatry 2018. [2] Kubicki et al., Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2014. [3] Hanlon et al., Schizophrenia research 2021. [4] Tamnes et al., J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2016. [5] Lv et al. Mol. Psychiatry. 2021 [6] Jensen & Helpern, NMR In Biomedicine 2010. [7] Jespersen, et al., Neuroimage 2018. [8] Zhang, NeuroImage 2011 [9] Henschel et al., Neuroimage 2020. [10] Fortin et al., Neuroimage 2017 [11] Cuenod et al., Molecular Psychiatry 2018. [12] Juurlink BH et al., Glia 1998. [13] Monin et al., Mol. Psychiatry 2015. [14] Smith et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000.Figures

Table 1: Groups descriptive statistics. CTRL: controls, EP: early psychosis, SCHZ: schizophrenia.

Figure 2: Group comparison (y-axis right) heatmaps of the BM test significance levels for each DTI, DKI and WMTI-W metric (y-axis left) and each region of interest (x-axis). The darker the color, the lower is the p-value; *:p≤5e-2, **:p≤1e-2, ***:p≤1e-3, ****:p≤1e-4. Red indicates the clinically more advanced group has higher values than the control (or less advanced) group; blue indicates the opposite.