4742

Anatomy and Image Contrast Metadata Verification using Self-supervised Pretraining

Ben A Duffy1 and Ryan Chamberlain1

1Subtle Medical Inc., Menlo Park, CA, United States

1Subtle Medical Inc., Menlo Park, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Data Processing

Automated metadata verification is essential for data quality checking. This study evaluates the extent to which self-supervised pretraining can improve performance on the anatomy and image contrast metadata verification tasks. On a small but diverse dataset, pretraining coupled with supervised finetuning, outperforms training from an ImageNet initialization, suggesting improved near out-of-distribution performance. On a larger brain-only dataset, training a linear classifier on the self-supervised pretrained network embeddings outperforms the corresponding ImageNet pretraining or random initialization on the image contrast prediction task. Cross-checking predictions against the DICOM metadata was an effective method for detecting artifacts and other quality issues.Introduction

Extracting meaningful information from the DICOM header is extremely challenging due to a lack of standardization across vendors and software versions. Furthermore, DICOM metadata often contains erroneous entries which can be problematic for downstream data processing. Automated metadata verification from image content is therefore imperative for data organization and data quality checking.In this study we evaluate the extent to which pretraining on unlabelled data improves performance on two different metadata verification tasks. This pretraining strategy has several advantages, namely improved performance on out-of-distribution data, a reduced requirement for manual annotations, and the ability to use the same encoder across different tasks rendering such systems significantly more maintainable. Here, we model near out-of-distribution data by using a small and diverse training dataset. In addition, on a larger but narrower distribution brain-only dataset, pretraining performance was assessed by appending a linear classifier to the network output.

Methods

Model Training: The BYOL1 framework was used for self-supervised pretraining. The advantage of using BYOL over contrastive learning approaches is the lack of the need for negative samples which are problematic to define in the medical imaging setting. BYOL is based on feeding two augmented views of an image to two separate networks and minimizing the RMSE loss between the online and target embeddings. For task specific fine-tuning a two-layer projection head was appended to the output of the ResNet50 encoder. To assess the performance of the pretraining regime, the pretrained network was compared against an ImageNet-initialized network in which the entire network was fine-tuned. For the brain-only task on the larger dataset, linear classifiers were trained on the embedding vectors.Datasets: Datasets containing images from a variety of different anatomies and image contrasts (T1, T1c, T2, T2FLAIR, SWI, DWI, STIR) were curated from three separate databases. Two of these were publicly available: IXI2 and OpenNeuro3, and one was in-house. (n=8196) MRI volumes were used for pretraining without labels. For the anatomy and image contrast prediction tasks, the dataset was split into train (n=331), and test (n=354). A smaller training dataset (n=165) was used to assess the extent to which self-supervised pretraining improved performance in the limited data regime. To assess the image contrast prediction performance on a single anatomy, a brain-only dataset containing six different contrasts (T1, T1c, T2, T2FLAIR, SWI, DWI) was split into train (n=5286) and test (n=1762) sets.

Evaluation: As the datasets were balanced across classes, classification accuracy was used as the primary evaluation metric across both tasks.

Results

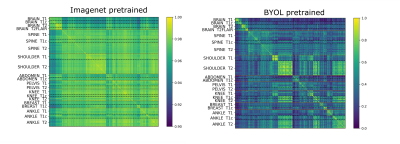

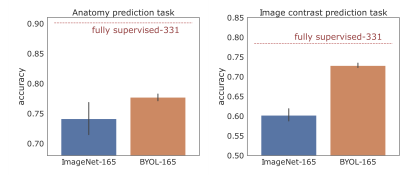

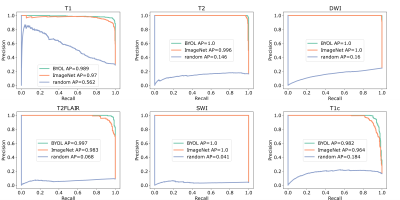

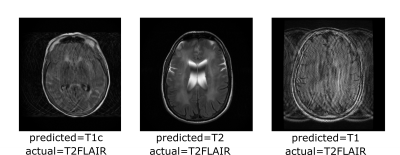

The correlation matrices between the embedding vectors of different volumes (Fig. 1) illustrate that the self-supervised pretraining is able to learn structure in the dataset that is not captured by the ImageNet pretrained network. Specifically, for the BYOL pretraining, there is high correlation between embeddings within sequences of the same anatomy and image contrast, resulting in a block diagonal correlation matrix when sorted by anatomy and sequence. In addition, anatomically similar musculoskeletal regions appear highly correlated e.g. ankle and knee. These findings suggested that the same encoder could be effective across different metadata verification tasks or as a strong initialization for fine-tuning.On the anatomy prediction and image contrast prediction tasks, the fully supervised accuracies were 90.1% and 78.4% respectively (Fig. 2). On the limited dataset (n=165), BYOL pretraining outperformed ImageNet on both anatomy prediction: 78.0±0.5% vs. 74.0±3.0% and image contrast prediction: 73±0.5% vs. 60±1.5%. On the brain-only dataset, the accuracy was 29% for random initialization vs. 95% for ImageNet vs. 98% for BYOL (Fig. 3). Where misclassifications occurred, these were frequently due to artifacts or miscalibrated tissue nulling sequences (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The performance was lower on the multi-anatomy dataset compared to the brain-only dataset due to the fact that it was designed to be small and diverse in order to test the near out-of-distribution performance of the BYOL pretraining. In addition, on the anatomy classification task, the 2D classifier sometimes failed to distinguish between different musculoskeletal body parts. In such cases, incorporating information across slices should improve performance.Practically, sharing embeddings across tasks and domains is extremely convenient as it negates the requirement to train from scratch, which is expensive, particularly for larger models. Finally, cross-checking the predicted contrast against that inferred from the DICOM metadata proved to be an effective way of detecting artifacts and other image contrast issues.

Conclusion

Here, we demonstrate that self-supervised pretraining is useful for reducing the labeling burden, improving near out-of-distribution performance and to help build more maintainable deep learning systems through the use of shared encoders across domains and tasks.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Grill, Jean-Bastien, et al. "Bootstrap your own latent-a new approach to self-supervised learning." Advances in neural information processing systems 33 (2020): 21271-21284.

2. https://brain-development.org/ixi-dataset/

3. https://openneuro.org/

Figures

Figure 1: Embedding correlation matrices between different volumes for embeddings generated from an ImageNet pretrained vs. BYOL pretrained network. (note: scale bars are different to adequately illustrate contrast)

Figure 2: Model performance in the limited data regime (n=165) for two different tasks: anatomy prediction and image contrast prediction. The fully supervised benchmark (n=331) is displayed for comparison (dashed red line).

Figure 3: Image contrast prediction performance on brain only data (n=1762). One vs. all precision recall curves for BYOL pretraining vs. ImageNet pretraining vs. random initialization. (AP: average precision)

Figure 4: Examples where the predicted image contrast did not match that inferred from the DICOM header. Frequently misclassifications occurred due to image artifacts or inadequate tissue nulling.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4742