4718

Solid state NMR in white matter: Unconventional 31P→1H cross polarization interrogates the proton pool1Physics and Astronomy, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2International Collaboration on Repair Discoveries (ICORD), University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3Radiology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 4UBC MRI Research Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Non-Proton, White Matter, myelin, phosphorus, hydrogen, spinal cord tissue, cross polarization, NMR, microstructure

Tools to better characterize myelin health are urgently needed. We demonstrate the use of the solid-state NMR techniques cross polarization (CP) and WIdeline Separation (WISE) to directly probe the phosphorous (31P) of phospholipid myelin bilayers and characterize protons (1H) involved in CP. This work demonstrates the feasibility of unconventional CP from 31P→1H in porcine spinal cord and investigates the contributing 1H. The results of this work provide crucial insight into the characteristics exploitable by CP in myelin and reinforce the potential of a two-step transfer of semi-solid 31P signals into aqueous 1H, providing a more direct and myelin-specific MRI signal.

Introduction

Many methods, including magnetization transfer (MT)1,2, myelin water fraction3,4, diffusion tensor imaging5, and inhomogeneous MT6, have been developed to study myelin in white matter. These methods each have strengths but are all relatively indirect measures of myelin lipids. We previously demonstrated7 that the solid-state NMR technique of cross-polarization8 (CP) could be used in white matter tissue to directly detect 31P in myelin lipids and that the solid-state 31P-NMR spectrum opens a new, more direct window to characterize myelin. Solid-state 31P-NMR signals should be very specific to myelin due to the abundance of phospholipid bilayers in myelin, and the abundance of 31P within those phospholipids 9. However, detection of the lipid 31P-NMR signals is relatively insensitive due to the broad linewidth of 31P. For this reason, we aim to transfer solid-state 31P signals into aqueous water, which exhibits high sensitivity, through CP followed by MT. Previously we showed the feasibility of such combined transfer in the opposite direction (1Haq→1Hlipids→31P). The objective of this work was to explore reversing the direction of CP (31P→1H) and study the environment of those 1H nuclei involved in CP transfer.Methods

157mg of porcine spinal cord, acquired from a local butcher, was loaded into a 5mm tube sealed with proton-free O-ring caps. NMR spectroscopy experiments were performed on a lab-built 8.4T NMR spectrometer10 at 22°C, with a horizontal coil double-resonant probe.Data acquisition:

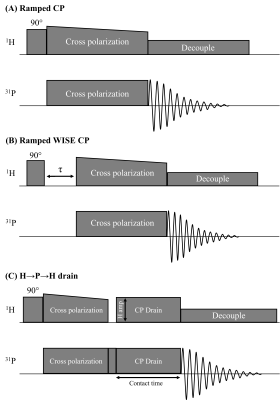

Fig.1 shows pulse sequences used in our study: a ramped amplitude CP11 sequence, a WIdeline SEparation (WISE)12 sequence, and a locally designed H→P→H CP drain sequence where the CP drain 1H amplitude and the contact time of the drain CP were varied in different experiments. RF field strengths of 27.8kHz were used (CP contact time=4ms, recycle delay time=3.5s, unless otherwise specified).

Results

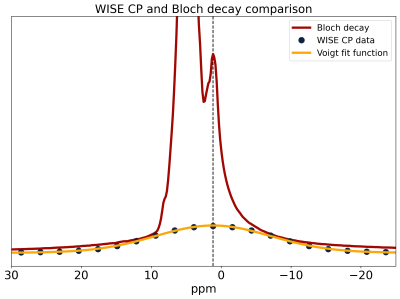

Fig.2 shows a comparison of 31P Bloch decay and CP spectra. The Bloch decay spectrum shows a sharp peak corresponding to 31P in solution superimposed upon a broad powder pattern, characteristic of phospholipid membranes13. The aqueous peak is absent in the CP spectrum, as the dipolar couplings necessary for CP are averaged away by rapid molecular tumbling in solution14. The lineshape of the 31P CP spectrum shows varying CP efficiency, with a ‘hole’ at the magic angle where intra-molecular dipolar couplings vanish. Some CP enhancement is visible where the lipid bilayer normal is parallel to B0 and the intra-molecular couplings are greatest.The WISE experiment yields the FID and spectrum of the 1H participating in CP. This spectrum is compared to a 1H Bloch decay spectrum which is dominated by the water peak with the lipids appearing as a small shoulder (Fig.3). The WISE spectrum differs significantly from the super-Lorentzian lineshapes typically used to model bilayers in tissue15,16, lacking the narrowest part of the super-Lorentzian line.

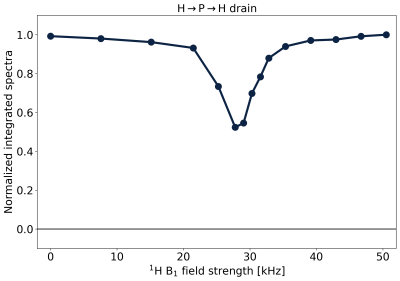

Fig.4 shows the results of the H→P→H drain when varying the 1H RF amplitude of the CP drain pulse. The Hartmann-Hahn match17 appears as a dip, where 31P magnetization is lost by CP back to 1H. The match condition is relatively narrow, as would be expected from the partially averaged dipolar couplings in the lipids.

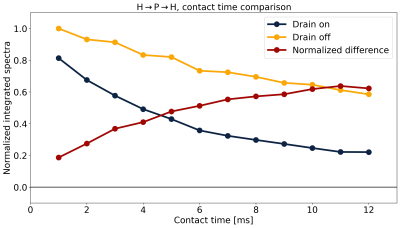

Fig.5 shows the effect of contact time in the H→P→H drain experiment with and without matched 1H irradiation to probe the size of the 1H pool involved in CP. The normalized difference between these experiments equilibrates at ~0.6, suggesting that on average each 31P is coupled to a pool consisting of two 1H.

Discussion

31P-NMR spectra show that CP in white matter is specific to the semi-solid tissue component and is sensitive to orientation. The WISE experiment shows that 1H participating in CP have linewidths comparable to those of the lipids observed in 1H Bloch decay spectra but lack the narrow peak of the super-Lorentzian. This is consistent with the ‘hole’ in the 31P spectrum at the magic angle. Both 31P(CP) and 1H(WISE) spectra suggest that bilayers normal to the magic angle are strongly suppressed by CP.The H→P→H drain experiments demonstrate that CP from 31P to 1H is detectable and that 31P nuclei are coupled to very small pools of approximately two 1Hs. This is in contrast to CP in rigid organic solids, where rare nuclei such as 31P are generally coupled to large baths of mutually coupled 1H, resulting in little orientation sensitivity, broad Hartmann-Hahn matches, and more uniform CP enhancement.

Ultimately, we wish to explore the feasibility of in vivo application of CP with detection in the 1H aqueous signal with a combined CP/MT sequence. One of several challenges is the direct detection of the 31P→1H CP signal in the presence of large 1H backgrounds. Gradient selection to suppress backgrounds will allow investigation of the CP signals in the 1H spectrum and allow the development and optimization of CP strategies for in vivo use.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated 31P→1H CP in white matter tissue and characterized the relevant 1H spin bath. Each 31P is dipolar-coupled to a small 1H pool, consisting of ~2 1H spins which are strongly coupled together. Future experiments will leverage these findings to study the feasibility of in vivo applications, and to further explore opportunities to study myelin.Acknowledgements

CL, PK, and CAM gratefully acknowledge funding from the NSERC (Canada) Discovery grants program. CAK thanks NSERC for a CGS-M Scholarship.

References

1. Stanisz, G.J., Kecojevic, A., Bronskill M.J., Henkelman RM. Characterizing White Matter With Magnetization Transfer and T2. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:1128-1136. doi:10.2307/2316017

2. Henkelman RM, Stanisz GJ, Graham SJ. Magnetization transfer in MRI: A review. NMR Biomed. 2001;14(2):57-64. doi:10.1002/nbm.683

3. Mackay A, Whittall K, Adler J, Li D, Paty D, Graeb D. In vivo visualization of myelin water in brain by magnetic resonance. Magn Reson Med. 1994;31(6):673-677. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910310614

4. Whittall KP, MacKay AL, Graeb DA, Nugent RA, Li DKB, Paty DW. In vivo measurement of T2 distributions and water contents in normal human brain. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37(1):34-43. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910370107

5. Le Bihan D, Mangin JF, Poupon C, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging: Concepts and applications. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13(4):534-546. doi:10.1002/jmri.1076

6. Manning AP, Chang KL, MacKay AL, Michal CA. The physical mechanism of “inhomogeneous” magnetization transfer MRI. J Magn Reson. 2017;274:125-136. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2016.11.013

7. Ensworth A, Knight C-A, Kozlowski P, Laule C, MacKay AL, Michal CA. 1H-31P Cross-polarization: A new frontier to study myelin in white matter. Ismrm. 2022.

8. Pines A, Gibby MG, Waugh JS. Proton-enhanced nuclear induction spectroscopy. a method for high resolution nmr of dilute spins in solids. J Chem Phys. 1972;56(4):1776-1777. doi:10.1063/1.1677439

9. Oliveira MJ, Águas AP. High concentration of phosphorus is a distinctive feature of myelin. An X-Ray elemental microanalysis study using freeze-fracture scanning electron microscopy of rat sciatic nerve. Microsc Res Tech. 2015;78(7):537-539. doi:10.1002/jemt.22506

10. Michal CA, Broughton K, Hansen E. A high performance digital receiver for home-built nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometers. Rev Sci Instrum. 2002;73(2 I):453. doi:10.1063/1.1433950

11. G M, X W, O SS. Ramped-Amplitude Cross Polarization in Magic-Angle-Spinning NMR. J Magn Reson Ser A. 1994;110:219-227.

12. Schmidt-Rohr KR, Clause J, Spiess HW. Correlation of Structure, Mobility, and Morphological Information in Heterogeneous Polymer Materials by Two-Dimensional Wideline-Separation NMR Spectroscopy. Macromolecules. 1992;25(12):3273-3277. doi:10.1021/ma00038a037

13. Murphy EJ, Rajagopalan B, Brindle KM, Radda GK. Phospholipid bilayer contribution to 31P NMR spectra in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 1989;12(2):282-289. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910120218

14. Filippov A V., Khakimov AM, Munavirov B V. 31P NMR Studies of Phospholipids. Vol 85. 1st ed. Elsevier Ltd.; 2015. doi:10.1016/bs.arnmr.2014.12.001

15. Wennerström H. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance lineshapes in lamellar liquid crystals. Chem Phys Lett. 1973;18(1):41-44. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(73)80333-1

16. Wilhelm MJ, Ong HH, Wehrli SL, et al. Direct magnetic resonance detection of myelin and prospects for quantitative imaging of myelin density. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(24):9605-9610. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115107109

17. Hartmann SR, Hahn EL. Nuclear double resonance in the rotating frame. Phys Rev. 1962;128(5):2042-2053. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.128.2042

18. Unterforsthuber K, Bergmann K. Mathematical separation procedure of broadline proton NMR spectra of crystalline polymers into components. J Magn Reson. 1979;33(3):483-495. doi:10.1016/0022-2364(79)90159-8

19. Bruce SD, Higinbotham J, Marshall I, Beswick PH. An Analytical Derivation of a Popular Approximation of the Voigt Function for Quantification of NMR Spectra. J Magn Reson. 2000;142(1):57-63. doi:10.1006/jmre.1999.1911

Figures