4707

From Survival to Survivorship: Cardiac MRI and Serum Biomarkers of Early Detection and Therapy for Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Mice

Margaret Caroline Stapleton1,2, Elizabeth Mazzella1,3, Noah Coulson1,2, George Cater4, Kristina Schwabb5,6, Sean Hartwick5,6, Thomas Becker-Szurszewski5,6, Devin Rain Everaldo Cortes1,2,7, and Yijen L. Wu1,2

1Department of Developmental Biology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 2Rangos Research Center Animal Imaging Core, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 3Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 4St. Clair Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 5Rangos Research Center Animal Imaging Core, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh PA, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 6Department of Pediatrics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 7Department of Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

1Department of Developmental Biology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 2Rangos Research Center Animal Imaging Core, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 3Department of Chemistry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 4St. Clair Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 5Rangos Research Center Animal Imaging Core, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh PA, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 6Department of Pediatrics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 7Department of Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, Toxicity

Anthracycline, like Doxorubicin (DOX), induced cardiotoxicity is a major cause of morbidity among childhood cancer survivors. Prior clinical studies diagnose using isolated measures of cardiac function, but by the time cardiotoxicity is detected, irreversible damage has already occurred. We hypothesize that multi-parametric cardiac MRI (CMR), and concurrent treatment with cardioprotective agents is a more sensitive biomarker for early diagnosis of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. We identified DOX cardiotoxicity by CMR derived LV strain and Luminex biomarker analysis prior to any decrease in EF and SV. Our study suggests multi-parametric CMR with concurrent cardioprotective treatment can be a surrogate endpoint for therapeutic efficacy.Introduction

Cardiotoxicity caused by anti-cancer anthracyclines, most prominently Doxorubicin (DOX), is a major cause of morbidity among childhood cancer survivors, especially survivors of childhood cancers [1]. They survive one life-threatening illness only to face another. Prior clinical studies used periodic measuring of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), such that if decreased ejection fraction is detected, then DOX treatment is stopped and the patients are given standard cardiovascular medicines to manage[2]. However, DOX-induced chronic cardiac dysfunction can continue to progress for many years, leading to cardiomyopathy, despite having managed the acute cardiac dysfunction. Currently, cardioprotective treatment strategies are limited in scope and monitoring preclinical changes are a challenge [3]. We hypothesize that multi-parametric cardiac MRI (CMR) can be a more sensitive biomarker for early diagnosis, prognosis and risk stratification of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity as it can detect fibrosis and edema. Further, concurrent treatment with cardioprotective agents, either by use of fat emulsion and reactive oxidation scavenger, Intralipid, or by use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) before irreversible damage occurs can also prevent DOX-induced cardiomyopathy.Method

Animal Model: C57BL6/J mice (n=5/group) underwent 5-week induction with 5mg/kg/wk DOX. Once group received concurrent oral ACEi captopril (DOX+CAP) treatment, and another was given a concurrent intralipid infusion (2g/kg) (DOX+LIPID). Vehicle control groups received saline.Multiparametric CMR: CMR was performed at baseline, 5 and 10 weeks. Multi-slice long-axis and short-axis cine MRI covering the whole heart volume with 20 cardiac phases per cardiac cycle was used to capture cardiac motion and allow quantification of global systolic function (LVEF). Strain analysis quantifies ventricular deformation throughout cardiac phases and can evaluate diastolic dysfunction and regional wall motion. Myocardial mass was also calculated from cine MRI.

Biomarker Analysis: At 10 weeks, cardiac serum was collected via left ventricle puncture for Luminex biomarker analysis.

Results

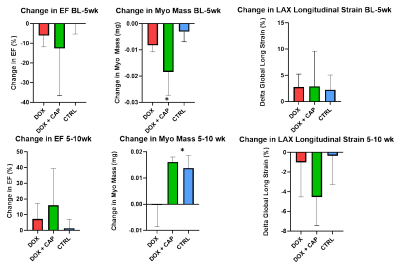

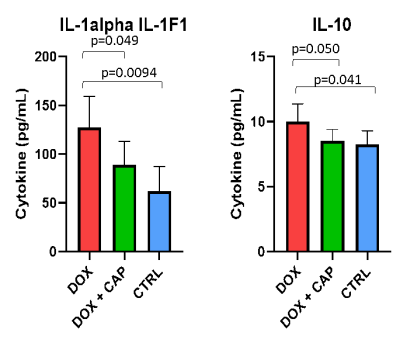

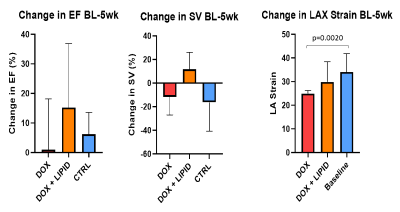

With CMR, we saw no change in LVEF between DOX treated and DOX+CAP or CTRL groups in either BL-5 weeks or 5-10 weeks. Instead, we observed a significant decrease in myocardial mass between DOX+CAP and CTRL groups at BL-5 weeks, but then saw CTRL and DOX+CAP myocardial mass both increased by the 10-week mark, such that DOX+CAP had significantly higher myocardial mass than DOX alone. This suggests that captopril has some cardioprotective abilities during the later stages of treatment. We saw no significant difference in LAX longitudinal strain between BL-5weeks or 5-10 weeks (Figure 2). Though we didn’t see any change in LVEF between DOX treated and DOX+CAP or CTRL groups, we did see a significant increase in IL-1α and IL-10 cytokine levels in cardiac serum samples. IL-10, also known as human cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor (CSIF), is an anti-inflammatory cytokine. IL-1α, a potent innate immune response cytokine, produced mainly by activated macrophages. (Figure 3) This also suggests that captopril has some cardioprotective ability. In the cohort that received concurrent intralipid treatment, we likewise saw no significant change in EF or stroke volume after 5 weeks of treatment. We did however, see that when compared to baseline, DOX LAX strain is significantly lower than baseline while DOX + LIPID is not (p values according to students 2-sided t-test) (Figure 4). This suggests the reactive oxidation scavenging property of intralipid also has some protective ability.Conclusion

We identified DOX cardiotoxicity by CMR derived LV strain and by Luminex biomarker analysis prior to any decrease in EF and SV. Cardioprotective agents reduced the cardiotoxic and inflammatory effect of concurrent DOX treatment. Our study suggests multi-parametric CMR with concurrent cardioprotective treatment can be a surrogate endpoint for therapeutic efficacy.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. McGowan, J.V., et al., Anthracycline Chemotherapy and Cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther, 2017. 31(1): p. 63-75.

2. Curigliano, G., et al., Cardiotoxicity of anticancer treatments: Epidemiology, detection, and management. CA Cancer J Clin, 2016. 66(4): p. 309-25.

3. Sawyer, D.B., et al., Mechanisms of anthracycline cardiac injury: can we identify strategies for cardioprotection? Prog Cardiovasc Dis, 2010. 53(2): p. 105-13.

Figures

Representative

example images of mid-slice CMR images are shown for animals treated with

doxorubicin, doxorubicin and captopril, doxorubicin and intralipid, and sham

saline.

Changes

in ejection fraction from baseline-5 weeks and 5-10 weeks showed no statistical

significance according to a one-way ANOVA. No significant changes in LAX

longitudinal strain at the 5 or 10 week time point are noted. There is a

statistically significant change in myocardial mass between DOX+CAP and

CTRL between 5-10 weeks, suggesting that

treatment with CAP has some cardioprotective abilities during the later stages

of treatment.

Detection

of IL-1alpha and IL-10 cytokine levels in cardiac serum samples taken from DOX,

DOX + CAP, and CTRL groups are significantly lower in DOX treated groups than

CTRL and DOX + CAP groups, suggesting ACEi could have a cardioprotective

ability (p-values are from a one-sided student’s t-test)

Changes

in ejection fraction and stroke volume from baseline-5 weeks show no

significant difference according to one-way ANOVA for any groups. Change in LAX

strain between BL and Week 5 shows that DOX LAX strain is significantly lower

than baseline while DOX + LIPID is not (p values according to students 2-sided

t-test).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4707