4695

Cardiac energetic deficit in a rat model of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF)

James A Goodman1, James D Quirk2, Xia Ge2, Yao Zhang1, and Rachel Roth-Flach1

1Pfizer, Inc, Cambridge, MA, United States, 2Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States

1Pfizer, Inc, Cambridge, MA, United States, 2Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, Cardiovascular, energetics

Cardiac energetics in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) may serve as a useful biomarker of disease status and therapeutic intervention. To evaluate the potential suitability of this endpoint as a biomarker in preclinical research, we assessed cardiac energetics in the ZSF1 obese rat model of HFpEF and ZSF1 lean control. This preclinical HFpEF model exhibited similar cardiac energetic deficits as do humans with HFpEF, indicating that that the PCr/γATP ratio may be a useful translational biomarker of disease status and intervention.Introduction

Patients with Heart Failure with preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) are characterized by reduced exercise capacity despite having preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). HFpEF patients have a ~23% deficit in cardiac energetics, as measured by the ratio of phosphocreatine (PCr) to ATP with 31P-MRS (1). To inform translational biomarker plans for potential candidate therapeutics and establish the relevance of cardiac energetics in this model, the goal of this effort is to determine whether energetic aspects of the clinical HFpEF phenotype is recapitulated in this ZSF1 obese rat model of HFpEF (2), both at rest and following a subcutaneous dobutamine challenge.Methods

All procedures performed on animals were in accordance with regulations and established guidelines and were reviewed and approved by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. 15 obese ZSF1 and ten lean ZSF1 rats were used for the HFpEF model and control, respectively. Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and a 24-gauge catheter was placed subcutaneously for delivery of dobutamine. Animals were then loaded into a restraint with a 2.5-cm surface coil tuned for 31P directly below the heart. Animals were then placed into an 8.6-cm 1H volume coil. Temperature, respiration, and ECG rates were recorded for the duration of the scan session. Scanning was performed on a 9.4 T Bruker MRI, and consisted of a 31P variable TR (VTR) saturation recovery T1 measurement (TR(s) = 20, 10, 5, 3, 1, 0.5, 0.13; BW = 10 kHz), a single slice short-axis bright blood cine (IgFLASH, TE=2.6 ms, TR=9.5 ms, res = 0.26 x 0.26 x 1.0 mm3, 20 frames/cycle), 30 minutes of serially-acquired 31P spectra (TR = 3 s, TE = 0.23 ms, BW = 10 kHz, 20 averages). Ten minutes after initiation of the serial spectra acquisition, 0.5 mg/kg dobutamine was delivered sub-cutaneously via the indwelling catheter line. Following dobutamine delivery, spectra were collected continuously another 20 minutes, followed by another cine acquisition. All 31P spectra were acquired with an outer-volume-suppressed NSPECT acquisition, which was achieved by sequential application of six adiabatically-excited saturation slabs surrounding the heart, followed by a non-localized excitation pulse (3). Spectral amplitudes and T1 relaxation time constants were estimated using the Bayesian Analysis Toolbox (4). To test the sensitivity of group comparisons to various correction factors, resonance amplitudes were corrected for T1 bias using jointly-estimated T1 values measured in the VTR scans and blood contamination of the γATP peak (5). Amplitudes were then averaged in 10-minute sections for baseline, 0 – 10 minutes post-dobutamine, and 10 – 20 minutes post post-dobutamine. LVEF was measured before and after the dobutamine challenge.Results

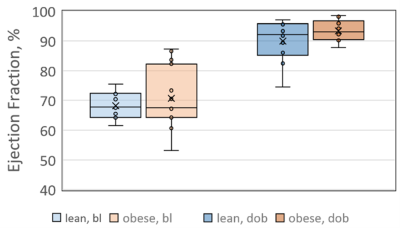

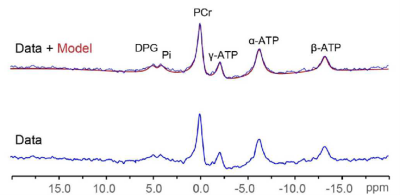

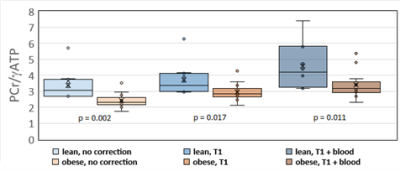

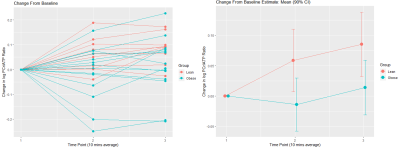

As expected, LVEF increased following dobutamine in both lean and obese animals. Groups were not significantly different from each other at baseline or after dobutamine challenge (figure 1). A representative one-minute cardiac 31P spectrum from the serial acquisition is shown in figure 2, along with the model fit from the Bayesian Analysis Toolbox. In the baseline condition, obese animals (n=14) had a significantly lower PCr/γATP ratio than lean animals (n=10) using uncorrected spectra (p = 0.002), T1-corrected spectra (p = 0.017), and T1- and blood-corrected spectra (p = 0.011) (figure 3). Group level differences in PCr/γATP change-from-baseline only reached significance in spectra corrected for both saturation and blood contamination (p=0.040 and p=0.047 for 0-10 minutes and 10-20 minutes post dobutamine, respectively) (figure4). All statistics were performed on log-transformed results to normalize the distributions and reduce sensitivity to outliers. Spectra from one obese animal was discarded due to exceptionally broad linewidths and poor spectral modeling.Discussion

This study was designed to enable dynamic assessment of acute response to a dobutamine challenge. High signal-to-noise ratio spectra were thus sought, leading to the selection of the outer-volume suppression approach that we took. While producing more signal than more localized approaches, there is increased signal contamination from the partial volume of blood. Blood contamination can be corrected using the 2,3-DPG peaks, though this introduces uncertainty due to difficulties in accurately modelling these low SNR resonances. If group-level blood volumes are not significantly different, then, depending on the context of use, these results suggest that blood contamination correction on the individual animal basis may not be beneficial. Residual contamination from intercostal muscle is also a possibility, and that may have impacted several spectra with exceptionally high PCr/γATP though that effect should be constant over the serial 31P spectra for a given rat. Irrespective of potential sources of contamination, the 20 – 30% reduction observed decrease of PCr/γATP in HFpEF model vs control animals at baseline is similar to what has been shown in humans with HFpEF vs healthy controls (1).Conclusion

The ZSF1 obese rat model of HFpEF appears to recapitulate the human phenotype with respect to cardiac energetic deficits, and may therefore be useful in evaluating therapeutic strategies that may impact cardiac energetic pathways.Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Pfizer, Inc. and conducted using the Washington University Small Animal Magnetic Resonance Facility.References

1. Burrage, et al., Circulation 2021; 144:1664-1678.

2. Schauer, et al. ESC Heart Failure 2020; 5:2123-2134.

3. Deschodt-Arsac, et al., PLOS One 2016; 11(9):e0162677.

4. Quirk, et al., Concepts in Magn. Reson. 2019; 47A:e21467.

5. Tyler et al., NMR in Biomedicine 2009; 22:405-413.

Figures

Ejection fractions measured at baseline (bl) and after

dobutamine challenge (dob). While LVEF

increases following dobutamine challenge, no group-level differences were

observed between lean and obese animals in either condition.

Representative one-minute 31P spectrum (blue) and overlay of

spectrum and model fit (red) from the serial acquisition, displayed with 30 Hz

line broadening.

Group level differences between obese ZSF1 HFpEF model rats

and lean ZSF1 control rats with no signal correction (left), partial saturation

correction (center), and blood + partial saturation correction (right). P-values are one-sided.

On average dobutamine increases PCr/ATP in lean animals, but

not in obese animals. Group level

change-from-baseline differences are significant at both time points (p=0.040

and 0.047, respectively). This effect

only reached significance for spectra corrected for both saturation and

blood-contamination. All data are shown

on a log-normalized scale.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4695