4688

Using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to assess advantages of cardiac-gated radioablation

Justin Poon1,2, Richard B Thompson3, Marc W Deyell4, Devin Schellenberg5, Kirpal Kohli6, and Steven Thomas2

1Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2Department of Medical Physics, BC Cancer - Vancouver, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 4Heart Rhythm Services and Centre for Cardiovascular Innovation, Division of Cardiology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5Department of Radiation Oncology, BC Cancer - Surrey, Surrey, BC, Canada, 6Department of Medical Physics, BC Cancer - Surrey, Surrey, BC, Canada

1Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2Department of Medical Physics, BC Cancer - Vancouver, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 4Heart Rhythm Services and Centre for Cardiovascular Innovation, Division of Cardiology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5Department of Radiation Oncology, BC Cancer - Surrey, Surrey, BC, Canada, 6Department of Medical Physics, BC Cancer - Surrey, Surrey, BC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Arrhythmia, Radiotherapy, cardiac radioablation

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) images and tracked left ventricle (LV) contour points were used to investigate the advantages of a cardiac-gated radioablation treatment for ventricular tachycardia. Contour points were divided into 17 segments of the LV. Individual segments were treated as hypothetical targets, and an optimal treatment window was determined where cardiac motion was minimal. Target centroid displacement and treatment area were quantified for the treatment window and the full cardiac cycle. Using a cardiac-gated radioablation treatment would allow for reduced treatment margins and minimize the dose delivered to surrounding normal tissue.Purpose

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is a rapid, abnormal heart rhythm caused by re-entrant electrical circuits that arise in scarred myocardium. Cardiac radioablation is a non-invasive treatment modality for VT that uses a medical linear accelerator to deliver radiation to the arrhythmogenic region within the heart.1–7 In a cardiac radioablation treatment, target margins must account for both respiratory and cardiac motion. Cardiac gating of radioablation treatment, where the radiation beam is only turned on during the quiescent interval of the cardiac cycle when heart motion is minimal, would help improve dose conformity and minimize the dose delivered to surrounding normal tissue.8–10 Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) cine images were used to demonstrate the advantages of gating a cardiac radioablation treatment, allowing for smaller treatment margins while maintaining target coverage. Healthy controls and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) patients, who would be more representative of VT patients, were included in the study.11,12Methods

CMR images and left ventricular (LV) epicardial (outer border) and endocardial (inner border) tracked contour points were analyzed for 5 healthy controls and 5 HFrEF patients. Images were acquired on a 1.5 T CMR scanner (Siemens Sonata, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using standard balanced steady state free precession (bSSFP) cine imaging and ECG gating within an 8–12 second breath-hold per slice. Two-chamber, three-chamber, and four-chamber view long axis slices with 25 or 30 reconstructed cardiac phases were analyzed for each patient. The original LV border points were first manually traced on the end-diastolic image frame, then propagated to all image frames over the cardiac cycle using a feature tracking non-rigid registration algorithm.12 In-house Python code was then used to generate additional border points and divide all points into segments according to the 17-segment model for the LV.13 Points were automatically segmented based on the slice view and position of each point relative to the LV long axis. To assess the effectiveness of a cardiac-gated radioablation technique, each slice segment (defined by the divided contour points) was treated as a hypothetical treatment target. The centroid of each segment was tracked to determine the optimum treatment window where cardiac motion was minimal during a fifth of the cardiac cycle. Maximum centroid displacement was determined for the full cardiac cycle and for the treatment window. The treatment area, defined by the range of motion for the segment border points, was also compared for the full cardiac cycle and the treatment window. For each patient, average centroid displacements and treatment areas were determined for the basal, mid-cavity, apical, and apical cap LV segment levels.Results

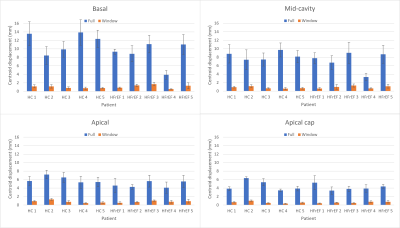

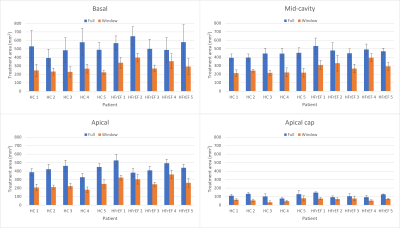

Reduction in target centroid displacement and treatment area was largest in the basal segments and decreased towards the apical cap. For the healthy control group, mean reduction in segment centroid displacement ranged from 10.7 ± 3.1 mm (basal) to 4.0 ± 1.1 mm (apical cap), and treatment area reduction ranged from 255.2 ± 110.4 mm2 (basal) to 55.2 ± 16.6 mm2 (apical cap). For the HFrEF patients, mean reduction in segment centroid displacement ranged from 7.7 ± 2.7 mm (basal) to 3.5 ± 1.2 mm (apical cap), and treatment area reduction ranged from 227.1 ± 97.4 mm2 (basal) to 42.9 ± 17.9 mm2 (apical cap). The gating method produced a smaller relative improvement for HFrEF patients, as relative reduction in treatment area for the different segment levels ranged from 33.2 ± 8.1 % to 39.6 ± 10.0 %, compared to a range of 47.2 ± 2.8 % to 50.9 ± 12.1 % for the healthy control group. The largest mean reduction in target centroid displacement for a single HFrEF patient was 9.7 ± 1.8 mm at the basal level. The largest treatment area reduction was seen in the same patient at the basal level: 286.8 ± 120.6 mm2 or a relative reduction of 48.0 ± 7.4 %. In comparison, the largest reduction in centroid displacement for a healthy control was 13.1 ± 2.9 mm at the basal level, corresponding to a treatment area reduction of 311.6 ± 121.8 mm2 or a relative reduction of 52.1 ± 7.0 %.Conclusions

The level of benefit provided by cardiac-gated radioablation methods varies depending on the treated area of the LV. Irradiating during an optimal treatment window of the cardiac cycle would be more beneficial when the target is closer to the basal LV, where cardiac motion is greatest, compared to apical segments. Cardiac gating resulted in a smaller relative reduction in target size for HFrEF patients compared to the healthy controls, since hearts with impaired function have reduced overall motion. However, cardiac gating would still lead to significant improvement in dose conformity, becoming more important in more dynamic hearts. A cardiac gating method would be effective for sparing adjacent healthy cardiac tissue and nearby organs-at-risk in cardiac radioablation treatments, but its suitability will depend on patient characteristics and the area of the heart to be treated.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (VCHRI) Innovation & Translational Research Award.References

- Loo Billy W., Soltys Scott G., Wang Lei, et al. Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy for the Treatment of Refractory Cardiac Ventricular Arrhythmia. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2015;8(3):748-750.

- Bhatt N, Turakhia M, Fogarty TJ. Cost-effectiveness of cardiac radiosurgery for atrial fibrillation: implications for reducing health care morbidity, utilization, and costs. Cureus. 2016;8(8):e720.

- Wang L, Fahimian B, Soltys SG, et al. Stereotactic Arrhythmia Radioablation (STAR) of Ventricular Tachycardia: A Treatment Planning Study. Cureus. 2016;8(7).

- Zei PC, Soltys S. Ablative radiotherapy as a noninvasive alternative to catheter ablation for cardiac arrhythmias. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017;19(9).

- Cuculich PS, Schill MR, Kashani R, et al. Noninvasive cardiac radiation for ablation of ventricular tachycardia. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(24):2325-2336.

- van der Ree MH, Blanck O, Limpens J, et al. Cardiac radioablation—A systematic review. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(8):1381-1392.

- Lydiard Pgd Suzanne, Blanck O, Hugo G, O’Brien R, Keall P. A Review of Cardiac Radioablation (CR) for Arrhythmias: Procedures, Technology, and Future Opportunities. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2021;109(3):783-800.

- Poon J, Kohli K, Deyell MW, et al. Technical Note: Cardiac synchronized volumetric modulated arc therapy for stereotactic arrhythmia radioablation — Proof of principle. Medical Physics. 2020;47(8):3567-3572.

- Akdag O, Borman PTS, Woodhead P, et al. First experimental exploration of real-time cardiorespiratory motion management for future stereotactic arrhythmia radioablation treatments on the MR-linac. Phys Med Biol. 2022;67(6).

- Reis CQM dos, Robar JL. Evaluation of the feasibility of cardiac gating for SBRT of ventricular tachycardia based on real-time ECG signal acquisition. Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics. n/a(n/a):e13814.

- Ezekowitz JA, Becher H, Belenkie I, et al. The Alberta Heart Failure Etiology and Analysis Research Team (HEART) study. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2014;14(1):91.

- Xu L, Pagano JJ, Haykowksy MJ, et al. Layer-specific strain in patients with heart failure using cardiovascular magnetic resonance: not all layers are the same. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2020;22(1):81.

- Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, et al. Standardized Myocardial Segmentation and Nomenclature for Tomographic Imaging of the Heart: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105(4):539-542.

Figures

Figure 1: Mean

centroid displacements for the basal, mid-cavity, apical, and apical cap left

ventricle segments during the full cardiac cycle (blue) and during the optimal

treatment window (orange) for 5 healthy controls and 5 heart failure with

reduced ejection fraction patients. The optimal treatment window was defined as

the fifth of the cardiac cycle with the minimum target centroid motion.

Figure 2: Mean

treatment area for the basal, mid-cavity, apical, and apical cap left ventricle

segments during the full cardiac cycle (blue) and during the optimal treatment

window (orange) for 5 healthy controls and 5 heart failure with reduced

ejection fraction patients. The optimal treatment window was defined as the

fifth of the cardiac cycle with the minimum target centroid motion.

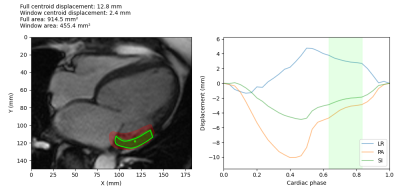

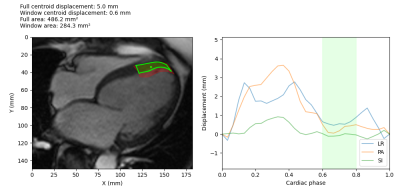

Figure 3: Example

treatment window determination for a HFrEF patient basal segment. The target

and centroid are shown on the left, overlaid on the CMR image. The treatment

area during the optimal window is shown in green, while the treatment area for

the full cardiac cycle is shown in red. The plot on the right shows the centroid

displacement in the left-right (LR), posterior-anterior (PA) and

superior-inferior (SI) directions, and the green shaded area shows the optimal

treatment window during the quiescent interval with the minimum motion.

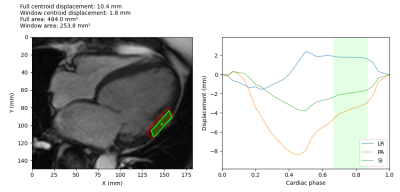

Figure 4: Example

treatment window determination for a HFrEF patient mid-cavity segment. The

target and centroid are shown on the left, overlaid on the CMR image. The

treatment area during the optimal window is shown in green, while the treatment

area for the full cardiac cycle is shown in red. The plot on the right shows

the centroid displacement in the left-right (LR), posterior-anterior (PA) and

superior-inferior (SI) directions, and the green shaded area shows the optimal

treatment window during the quiescent interval with the minimum motion.

Figure 5: Example

treatment window determination for a HFrEF patient apical segment. The target

and centroid are shown on the left, overlaid on the CMR image. The treatment

area during the optimal window is shown in green, while the treatment area for

the full cardiac cycle is shown in red. The plot on the right shows the

centroid displacement in the left-right (LR), posterior-anterior (PA) and

superior-inferior (SI) directions, and the green shaded area shows the optimal

treatment window during the quiescent interval with the minimum motion.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4688