4685

CMR Myocardial Strain Analysis in Discriminating Obstructive Sleep Apnea-Hypopnea Syndrome Induced Heart Failure and Dilated Cardiomyopathy1Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, China, 2Philips Healthcare, Beijing, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Heart, Cardiovascular, Cardiac magnetic resonance; Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome; Dilated cardiomyopathy

The obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) patients with heart failure and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) patients all show left ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction as the main phenomenon. Still, there are very few reports on identifying the two diseases. Herein cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) myocardial strain technology was used to evaluate the cardiac function and myocardial structure of the OSAHS and DCM patients. The results showed that the global peak circumferential and longitudinal strains and the left ventricular myocardial mass of the DCM group were lower than the OSAHS group. This research provides reference for the identification of these two diseases.Introduction

As reported, there are nearly a billion adults aged between 30 and 69 suffering from obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) worldwide. Many studies have revealed changes in the cardiac structure and function of the OSAHS patients[1,2], and severe OSAHS induces more significant cardiac structure and function changes[3,4]. However, distinguishing dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) from OSAHS-induced heart failure is difficult in imaging diagnosis. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), as a promising examination method, could provide reliable information on cardiovascular morphology, function, and perfusion, assessing myocardial activity. Therefore, it has become the "gold standard" for noninvasive assessment of cardiac function and structure[5].Materials and Methods

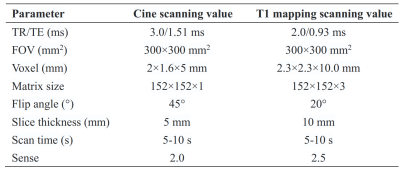

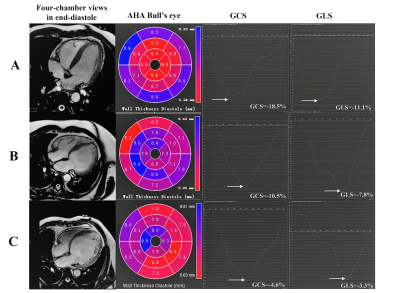

Cardiac MRI was performed with 3.0 T MRI systems (Ingenia Elition, Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) using a 32-channel phased-array abdomen coil. The protocol consisted of cine imaging and native and enhanced T1 mapping imaging for analysis. Standard cine images were obtained from end-expiratory breath hold steady-state free precession sequences (SSFP). The native T1 mapping was performed by a modified look-locker inversion recovery (MOLLI). Then, the enhanced T1 mapping images were obtained after 15 minutes of delayed enhancement.The acquisitions of SSFP cine were conducted in 2-chamber, 3-chamber, and 4-chamber long-axis planes, as well as a stack of contiguous short-axis slices, which encompassed the left ventricle from the atrioventricular ring to the apex. Cine images were obtained using a steady-state free precession (SSFP) sequence with a breath-hold and ECG trigger for cardiac morphologic and functional analyses. Native and enhanced T1 mapping was achieved at the basal, middle, and apical short axis of the left ventricular slice. The scanning parameters were showed in Table1. All the analyses were conducted by two investigators with more than 5 years of experience using the commercial software CVI 42 (Circle Cardiovascular Imaging, Calgary, Canada). Cardiac functional parameters were computed automatically. Feature-tracking was performed on standard long-axis cine (two, three, and four-chamber views) and short-axis cine to calculate the LV peak strain parameters, including global circumferential strain (GCS), global longitudinal strain (GLS), global radial strain (GRS). According to CVI software, the values of native and enhanced T1 and the extracellular volume fraction (ECV) were automatically measured by manually delineated mid-layer myocardium of left ventricular basal, middle and apical segments.

Results

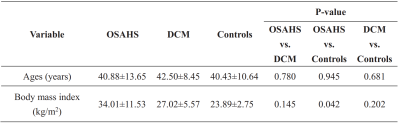

This study includes 16 patients (8 patients with severe OSAHS, 8 patients with DCM), and 7 healthy volunteers. Due to the bad image quality, the extracellular volume (ECV) fraction value of 1 patient in the OSAHS group was excluded.The baseline characteristics of the patients were provided in Table 2, showing no significant differences in age between the groups. Compared to the Controls group, the OSAHS group has a higher body mass index (BMI). There were no statistical differences in the BMI among the patients’ groups (the OSAHS and DCM groups).

Compared with the control group, the patients have significantly lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), smaller EDV, and also smaller ESV (P < 0.001), as shown in Table 3. There were no significant differences between the OSAHS and the DCM group in terms of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), end-diastolic volume (EDV), end-systolic volume (ESV), stroke volume (SV), and cardiac output (CO).

Importantly, the global peak circumferential, radial, and longitudinal strains and the left ventricular myocardial mass of the DCM group are all lower than that of the OSAHS group. Still, only the circumferential and longitudinal strains and the left ventricular myocardial mass show statistical significance (P < 0.05). In addtion, there is no statistical difference in ECV value between the OSAHS and the DCM groups (P>0.05).

Conclusions

In conclusion, myocardial mass and left ventricular circumferential and longitudinal myocardial strain could help differentiate severe OSAHS from DCM.Acknowledgements

The support from the Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University is sincerely acknowledged.References

1. Shamsuzzaman AS, Gersh BJ, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnea: implications for cardiac and vascular disease. Jama 2003, 290(14):1906-1914.

2. Li T, Ou Q, Zhou X, Wei X, Cai A, Li X, Ren G, Du Z, Hong Z, Cheng Y, Liu H. Left ventricular remodeling and systolic function changes in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a comprehensive contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance study. Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy 2022, 12(4):436.

3. Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O'Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiological Reviews 2010, 90(1):47-112.

4. Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, Lee ET, Newman AB, Javier Nieto F, O'Connor GT, Boland LL, Schwartz JE, Samet JM. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the sleep heart health study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2001, 163(1):19-25.

5. Peng P, Lekadir K, Gooya A, Shao L, Petersen SE, Frangi AF. A review of heart chamber segmentation for structural and functional analysis using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 2016, 29(2):155-195.

Figures