4671

Using Dynamic Mode Decomposition for Functional Lung Imaging1Computer Assisted Clinical Medicine, Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany, 2Mannheim Institute for Intelligent Systems in Medicine, Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Lung, Data Processing

Fourier Decomposition and related techniques have demonstrated the viability of obtaining regional pulmonary functions. To this end, novel post-processing techniques have been previously proposed to obtain ventilation and perfusion related information from dynamic acquisitions. To improve upon these methods, here we propose the use of an advanced data processing framework based on dynamic mode decomposition (DMD) for functional lung MRI. Phantom and in vivo results indicate that DMD achieves similar performance compared to established techniques and improves robustness in cases with fewer number of measurements.Introduction

Fourier Decomposition (FD)1 and related methods have been demonstrated as viable options for acquiring information on regional pulmonary functions. These methods utilize Fourier transform to spectrally analyse registered dynamic acquisitions and to identify ventilation and perfusion related signal changes. However, the Fourier transform of incomplete time-series signals can lead to deviations in estimated amplitudes2.To improve robustness of respiratory and cardiac amplitude estimation, windowed FD approaches3 and matrix pencil decomposition (MP)4 were previously proposed; where the former suffers from lower scan efficiency and the latter relies on Hankel matrices and is not able to identify the system matrix5.

Here, we propose the use of dynamic mode decomposition6 (DMD) for the analysis of spatiotemporal features in the dynamic acquisitions. We present results from a synthetic phantom and in vivo results from a volunteer to demonstrate the performance of the DMD method.

Methods

Consider the measurement of a discrete-time linear dynamic system that is sampled at every $$$\Delta t$$$ in time, so that $$$x_k=x(k\Delta t)$$$ and $$$k=1,2,...,m$$$. It is possible to arrange the measurements into two matrices as:$$X=\begin{bmatrix}|&|&&|&|\\x_1&x_2&...&x_{m-2}&x_{m-1} \\|&|&&|&|\end{bmatrix},$$

$$X'=\begin{bmatrix}|&|&&|&|\\x_2&x_3&...&x_{m-1}&x_{m} \\|&|&&|&|\end{bmatrix}$$

For these measurements, an operator $$$A$$$ which approximates the relationship between the measurements can be written as7:

$$A\triangleq X'X^\dagger$$

where the $$$\cdot^\dagger$$$ is the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse. The dynamic mode decomposition is obtained by eigendecomposition of the system matrix $$$A$$$, where the eigenvalues represent the DMD modes.

DMD can be calculated efficiently by introducing an approximation of the system matrix, denoted by $$$\tilde A$$$, where the leading eigenvalues and eigenvectors are the same. In this case, a rank-reduced singular value decomposition (SVD) of $$$X = U \Sigma V^*$$$ is computed, and $$$\tilde A$$$ is defined as $$$\tilde A \triangleq U^*X'V\Sigma^{-1}$$$. Next, the eigendecomposition of $$$\tilde A W = W\Lambda$$$ is computed, and the eigendecomposition of $$$A$$$ is reconstructed using $$$W$$$ and $$$\Lambda$$$. Lastly, the DMD modes of $$$A$$$ are computed as $$$\Phi = X'V\Sigma^{-1}W$$$.

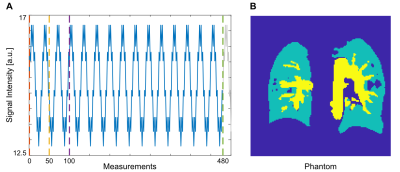

For evaluation of the proposed method, a synthetic phantom was generated with $$$m=480$$$ measurements for complete time series and included three tissue types: background, large vessels, and lung parenchyma. For parenchyma, both ventilation and perfusion related signal changes were simulated according to modified Lujan formulation6, whereas for large vessels perfusion related changes were simulated. The simulated signal and the phantom are illustrated in Figure 1.

Functional maps obtained with DMD were compared to maps obtained with FD and MP methods. To evaluate robustness across different number of measurements, maps were obtained for $$$m=50$$$, $$$m=100$$$ and $$$m=480$$$. To evaluate noise performance, maps were obtained from noisy measurements. To achieve this, separate bivariate Gaussian noise instances were added to simulated dynamic images. For quantitative analysis, SSIM measurements were utilized. Here, functional maps obtained via FD from noiseless complete time-series with $$$m=480$$$ were taken as reference.

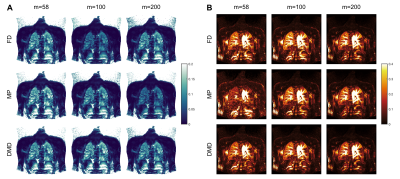

For in vivo demonstrations, bSSFP acquisitions from a volunteer were utilized6. To this end, two complete time-series with $$$m=58$$$ and $$$m=200$$$, and an incomplete series with $$$m=100$$$ were obtained from the acquisitions.

Results

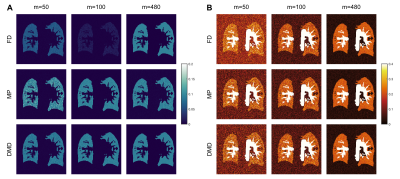

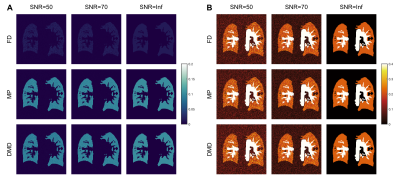

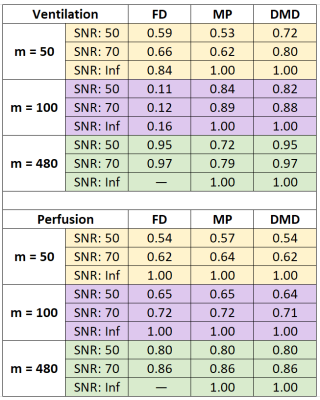

Figure 2 shows functional maps obtained from the synthetic phantom at SNR=50 across various $$$m$$$. While all methods estimate similar perfusion amplitudes, FD methods suffer in estimating ventilation amplitudes in cases of incomplete time-series. In comparison, we observe that both MP and DMD improve ventilation amplitude estimation, and additionally DMD is able to estimate maps more accurately even in cases with limited number of measurements. Figure 3 shows functional maps obtained at two different SNR levels as well as the noiseless case for $$$m =100$$$. Here, both MP and DMD successfully generate functional maps across different noise levels.SSIM results obtained from the synthetic phantom are reported in Table 1. We observe that perfusion maps obtained with all methods display similar performance across $$$m$$$ and noise levels. Meanwhile, DMD improves the ventilation map quality compared to both FD and MP for $$$m=50$$$.

Figure 4 displays functional maps obtained from a heathy volunteer for three different $$$m$$$. We observe that FD fails to estimate ventilation amplitude for $$$m=100$$$, whereas MP fails to estimate ventilation amplitude for $$$m=200$$$ and perfusion amplitude for $$$m=58$$$. Meanwhile, DMD is able to estimate correct amplitudes across different measurement series.

Discussion & Conclusion

Our phantom results indicate that DMD improves identification of ventilation and perfusion amplitudes compared to FD and MP, especially from fewer number of measurements. Similarly, our in vivo results indicate that DMD is able to estimate respective amplitudes more accurately compared to MP, and without the complete time-series requirement of FD.Furthermore, DMD enables the identification of the dynamic system matrix. As such, DMD allows a physical interpretation of measurements and influences in terms of spatial structures and their associated temporal responses5. Thus, in addition to the identification of dominant frequencies and amplitudes, DMD allows for state estimation or future-state predictions6. Moreover, DMD may be further improved with the incorporation of compressed sensing6 to exploit sparsity in MR acquisitions8.

In this work, we have demonstrated a novel data processing framework for obtaining functional maps from dynamic acquisitions. While further studies are warranted, our preliminary results indicate that DMD successfully estimates signal amplitudes under noise and displays improved robustness in cases where limited number of measurements are available.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant number: DFG 397806429).References

1. Bauman G, Puderbach M, Deimling M, et al. Non-contrast-enhanced perfusion and ventilation assessment of the human lung by means of Fourier decomposition in proton MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2009; 62(3):656-664.

2. Lin YY, Hodgkinson P, Ernst M, et al. A Novel Detection–Estimation Scheme for Noisy NMR Signals: Applications to Delayed Acquisition Data. J. Magn. Reson. 1997; 128(1):30-41.

3. Ilicak E, Ozdemir S, Schad LR, et al. Phase-cycled balanced SSFP imaging for non-contrast-enhanced functional lung imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2022; 88:1764-1774.

4. Bauman G, and Bieri O. Matrix pencil decomposition of time-resolved proton MRI for robust and improved assessment of pulmonary ventilation and perfusion. Magn. Reson. Med. 2017; 77:336-342.

5. Alassaf A, and Fan L. Randomized Dynamic Mode Decomposition for Oscillation Modal Analysis. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021; 36(2):1399-1408.

6. Kutz, JN, Brunton SL, Brunton BW, and Proctor JL. Dynamic Mode Decomposition. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 2016.

7. Tu JH, Rowley CW, Luchtenburg DM, et al. On dynamic mode decomposition: Theory and applications. J. Comput. Dyn. 2014; 1(2):391–421.

8. Ilicak E, Saritas EU, and Çukur T. Automated Parameter Selection for Accelerated MRI Reconstruction via Low-Rank Modeling of Local k-Space Neighborhoods. Z. Med. Phys. 2022.

Figures