4657

Dynamic lung water imaging during exercise stress1National Heart, Lung , and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Lung, Exercise MRI

Dynamic quantification of lung water during exercise stress is of clinical interest for early diagnosis of heart failure. In this study, we demonstrate a method to derive quantitative time-resolved lung water density maps from a continuous 3D MRI acquisition during supine exercise stress by using a motion corrected sliding-window image reconstruction. An animal model of dynamic lung water accumulation was used to validate the method, and feasibility was demonstrated in healthy subjects imaged in transitions between rest and exercise, measuring a lung water density increase of 23±10% during peak exercise.Introduction

Shortness of breath during physical activity is an early symptom of heart failure which is caused by an accumulation of lung water. This lung water accumulation is the result of fluid leaking from the vasculature into the pulmonary extravascular space, driven by an abnormal exercise-induced increase in pulmonary blood pressure1. Dynamic quantification of lung water during exercise stress is therefore of interest to unmask latent heart failure. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has recently been proposed as a promising method to measure lung water, and has been demonstrated in images acquired at rest or shortly after, but not during, exercise2–6. In this study, we develop a method for dynamic lung water imaging during exercise stress. We apply it to healthy subjects performing supine exercise while being scanned, and validate it with a porcine model of mitral regurgitation.Methods

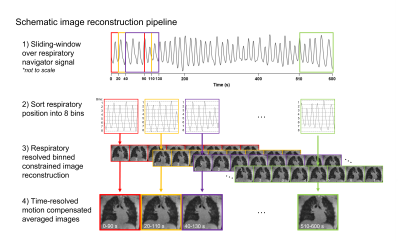

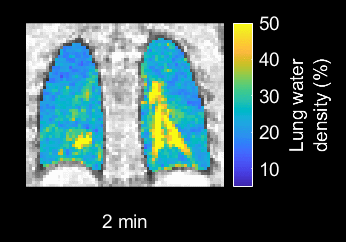

In this IRB- and IACUC-approved study, we continuously measured lung water using a 3D self-gated stack-of-spiral proton density weighted gradient echo sequence (TE/TR/θ = 0.56ms/9ms/1°, 831 in-plane golden angle spiral interleaves, 5.0 ms readout, 3.5x3.5x3.5 mm resolution, 450x450x252 mm FOV) at 0.55T MRI (prototype MAGNETOM Area, Siemens)7,8. To derive time-resolved images for dynamic assessments, we implemented a motion-corrected sliding-window compressed sensing image reconstruction with spatial and temporal total variation constraints. The sliding-window sampled 90s of data with a 20s temporal increment (Figure 1)7,9–11.Dynamic 3D pixel-wise lung water density (LWD) maps were derived using an automated image processing pipeline including a neural network for lung segmentation and a signal intensity-based coil shading correction4. LWD maps were computed as the ratio of the signal intensity in the lungs to the surrounding body tissue, assuming a 70% musculoskeletal water density4,5, and dynamic ΔLWD was calculated as the percentage change in global and regional LWD over time.

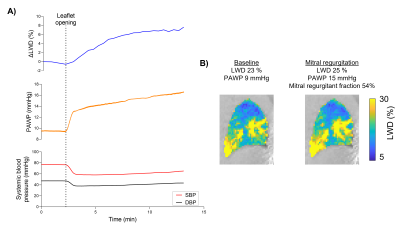

To validate the capability of detecting lung water dynamics, we used a controlled porcine model of severe mitral regurgitation which triggers an accumulation of lung water. Regurgitation was dynamically induced inside the MRI while imaging by applying tension on a suture placed across the anterior mitral leaflet, that was externalized through a femoral vascular sheath12,13. Lung water accumulation was imaged in 4 pigs (40±2kg) over 1h, and was corroborated by simultaneous recordings of pulmonary arterial wedge pressures (PAWP) and systemic systolic and diastolic femoral arterial blood pressures (SBP/DBP). Cardiac short-axis-stack cine and retrospectively ECG-gated aortic flow images were acquired for the purposes of measuring cardiac output and mitral regurgitation.

Exercise imaging was performed in 12 healthy subjects (27±5yrs, 3 women) using an MRI-compatible supine pedal ergometer (ErgoSpect) with 60-90W resistance. The imaging protocol in healthy subjects comprised of four 10-minute acquisitions:

- 10 minutes at rest

- Vigorous exercise test targeting maximum heart rate by age

- Moderate exercise with stride 60 steps/minute imaging the transition from rest to exercise

- Transition from moderate exercise to rest.

Results

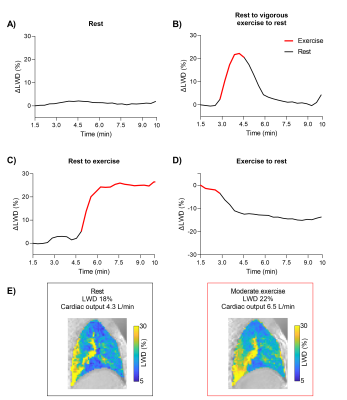

Dynamic LWD imaging during induction of mitral regurgitation and exercise stress was feasible in animals and humans, and dynamic changes were measured, as illustrated in the Figure 2 animation. The porcine experiments yielded a mitral regurgitant fraction of 53±21% and an increase in ΔLWD of 4.6±1.0%. PAWP increased by 75±44% (6.5±3 mmHg), and SBP/DBP decreased by -23±15/-20±15% (Figure 3). Cardiac output decreased from 3.9±0.8 to 2.7±0.6L/min, p=0.007, suggesting that measured ΔLWD was extravascular.Healthy subject exercise imaging measured a ΔLWD of 14±8% after 5 minutes of moderate exercise, and peaked at 23±10% during vigorous exercise (Figure 4). When transitioning from moderate exercise to rest, ΔLWD decreased by -9±8%. We hypothesize these changes in LWD is explained by an increased intravascular pulmonary fluid during exercise, as the cardiac output increased from 5.1±1.2 at rest to 8.7±1.4L/min at moderate exercise, p<0.0001. Lung water remained unchanged over 10 minutes at rest (ΔLWD 0.0±2.4%, p=0.99).

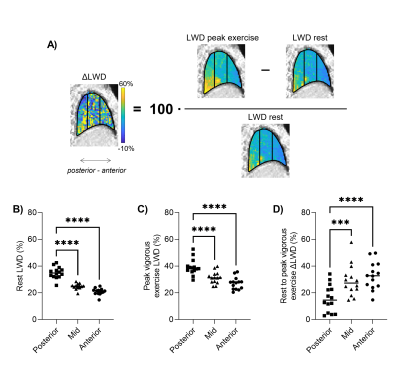

LWD was higher posteriorly compared the anterior parts of the lungs both at rest (35±4% vs 21±2%, p<0.0001) and peak vigorous exercise (39±6% vs 27±5%, p<0.0001), but a larger ΔLWD was measured anteriorly (33±10%) compared to posteriorly (16±10%), p<0.0001 (Figure 5). This reflects an increase in pulmonary perfusion during exercise.

Discussion

This study presents a method which was capable of depicting and quantifying LWD dynamics in a controlled animal model of mitral regurgitation, and in healthy subjects during supine exercise stress. The acquired 3D images have isotropic resolution, allowing re-slicing and visualization in any orientation, and regional LWD analysis. The method does not, however, distinguish between intravascular and extravascular fluid and the measured LWD increase in healthy subjects is attributed to an exercise-induced increase in intravascular pulmonary fluid. Patient studies are warranted to determine if this method can unmask latent heart failure, where an additional extravascular lung water accumulation is expected, in line with the pig model results where the LWD increased despite a decrease in cardiac output.Conclusion

In conclusion, dynamic changes in lung water density can be dynamically quantified using a continuous 3D MRI acquisition with a sliding-window and motion corrected image reconstruction.Acknowledgements

We thank Scott Baute, Christine Mancini, Andrea Jaimes, William H. Schenke, John Kakareka, Victoria Frasier, and Katherine Lucas for their assistance with this project. The authors would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Siemens Healthcare in the modification of the prototype MAGNETOM Aera MRI system for operation at 0.55T, and in the stack-of-spirals UTE sequence, under an existing cooperative research agreement (CRADA) between NHLBI and Siemens Healthcare.References

1. Devroey D., Van Casteren V. Signs for early diagnosis of heart failure in primary health care. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2011;7(1):591–6. Doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S24476.

2. Thompson RB., Chow K., Pagano JJ., et al. Quantification of lung water in heart failure using cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2019;21(1):58. Doi: 10.1186/s12968-019-0567-y.

3. Burrage MK., Hundertmark M., Valkovič L., et al. Energetic Basis for Exercise-Induced Pulmonary Congestion in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2021;144(21):1664–78. Doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.054858.

4. Seemann F., Javed A., Chae R., et al. Imaging gravity-induced lung water redistribution with automated inline processing at 0.55 T cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2022;24(1):35. Doi: 10.1186/s12968-022-00862-4.

5. Meadus WQ., Stobbe RW., Grenier JG., Beaulieu C., Thompson RB. Quantification of lung water density with UTE Yarnball MRI. Magn Reson Med 2021;86(3):1330–44. Doi: 10.1002/mrm.28800.

6. Rocha BML., Cunha GJL., Freitas P., et al. Measuring lung water adds prognostic value in heart failure patients undergoing cardiac magnetic resonance. Sci Rep 2021;11(1):20162. Doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99816-6.

7. Javed A., Ramasawmy R., O’Brien K., et al. Self-gated 3D stack-of-spirals UTE pulmonary imaging at 0.55T. Magn Reson Med 2022;87(4):1784–98. Doi: 10.1002/mrm.29079.

8. Campbell-Washburn AE., Ramasawmy R., Restivo MC., et al. Opportunities in interventional and diagnostic imaging by using high-performance low-field-strength MRI. Radiology 2019;293(2):384–93. Doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019190452.

9. Zhu X., Chan M., Lustig M., Johnson KM., Larson PEZ. Iterative motion-compensation reconstruction ultra-short TE (iMoCo UTE) for high-resolution free-breathing pulmonary MRI. Magn Reson Med 2020;83(4):1208–21. Doi: 10.1002/mrm.27998.

10. Zachiu C., Papadakis N., Ries M., Moonen C., Denis De Senneville B. An improved optical flow tracking technique for real-time MR-guided beam therapies in moving organs. Phys Med Biol 2015;60(23):9003–29. Doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/23/9003.

11. Zachiu C., Denis De Senneville B., Moonen C., Ries M. A framework for the correction of slow physiological drifts during MR-guided HIFU therapies: Proof of concept. Med Phys 2015;42(7):4137–48. Doi: 10.1118/1.4922403.

12. Babaliaros VC., Greenbaum AB., Khan JM., et al. Intentional Percutaneous Laceration of the Anterior Mitral Leaflet to Prevent Outflow Obstruction During Transcatheter Mitral Valve Replacement: First-in-Human Experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2017;10(8):798–809. Doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.01.035.

13. Piérard LA., Lancellotti P. The Role of Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation in the Pathogenesis of Acute Pulmonary Edema. N Engl J Med 2004;351(16):1627–34. Doi: 10.1056/nejmoa040532.

14. Ramasawmy R., Campbell-Washburn AE., Lederman RJ., Herzka D. Real-time and self-gated flow using a golden-angle spiral trajectory. Proc. Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB, Paris, France. 2018. p. 688.

Figures