4655

MRI of the diaphragm: characterizing motion and microstructural properties in ICU patients1Intensive Care, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, Netherlands, 2Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Rotterdam, Netherlands, 3Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 4Division of X-Ray imaging and CT, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany, 5Hopp Children's Cencer Center Heidelberg (KiTZ), Heidelberg, Germany, 6Clinical Cooperation Unit Pediatric Oncology, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), Heidelberg, Germany, 7National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT), Heidelberg, Germany, 8Department of Physiology, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Lung, Motion Correction, Diaphragm

Diaphragm weakness is common in intensive care patients and has a detrimental effect on clinical outcome. Weakness in these patients may be explained by disuse atrophy or injury resulting from systemic inflammation among other factors. MRI can be used to study the motion and tissue characteristics of the diaphragm. We present the design of an MRI protocol for quantifying motion and tissue characteristics of the diaphragm. 4D MRI, relaxometry and dynamic contrast enhanced MRI were successfully applied in healthy volunteers and COVID-19 patients. Our method may aid in finding treatments and prevention strategies for diaphragm weakness in critically ill patients.Introduction

At the Intensive Care unit (ICU), invasive mechanical ventilation is a lifesaving intervention for critically ill patients with severe respiratory failure, such as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, inadequate ventilator support during mechanical ventilation has been linked to the development of diaphragm weakness1-8, which is associated with increased mortality and risk of complications, difficulties weaning off the ventilator and prolonged ICU-stay4,9,10. Moreover, increased muscle fibrosis was found in biopsies of the diaphragm of mechanically ventilated patients and deceased COVID-19 patients11-13, suggesting additional diaphragm tissue injury. It is largely unknown whether and how these diaphragm injuries affect its motion.To better understand the effects of mechanical ventilation and critical illness on the diaphragm, we aimed at visualizing the 4D motion of the diaphragm of COVID-19 patients after a prolonged period of mechanical ventilation and quantifying its tissue characteristics using relaxometry and dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI. These insights can ultimately be used to find strategies for prevention and treatment of diaphragm weakness.

However, MR imaging of the diaphragm, with normal thickness of less than 2 mm, poses several challenges, including the needs for sufficient spatial resolution and respiratory motion compensation. Few studies report diaphragm motion14-17 using 2D cine MRI. However, it is difficult to capture the complicated 3D architecture of the diaphragm with 2D imaging. Moreover, advanced tissue characterization, such as obtained with DCE MRI, would be highly desired.

Here, we present the first MR protocol that enables 4D motion and tissue property characterisation of the diaphragm.

Methods

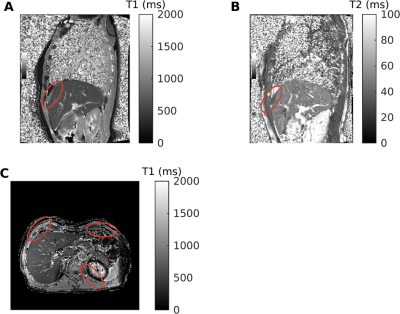

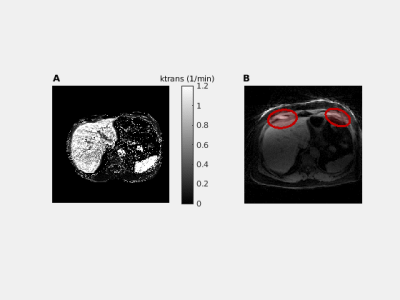

To date, five healthy controls (three women) and three recently (<7 days) ICU-discharged male patients admitted for COVID-19 pneumonia and invasively ventilated for at least 72 hours were imaged on a 1.5T MAGNETOM Sola system (Siemens Healthcare) (Table 1). Our proposed advanced sequences consisted of free-breathing 3D acquisitions. To verify our techniques, we also obtained gold-standard 2D conventional reference images with breath holds (~10s). The breath holds are challenging for the patients, limiting clinical use, but these 2D images can function as validation for our advanced techniques.For studying motion, we implemented a 4D joint motion-compensated high-dimensional total variation (4D joint MoCo-HDTV, advanced method) reconstruction of a golden-angle radial sparse parallel (GRASP) acquisition to generate dynamic images of 20 respiratory phases18. To validate the 4D joint MoCo-HDTV, a 2D conventional14 bSSFP real-time cine acquisition was used in three slices as reference. To assess functional tissue characteristics, we performed T1 mapping before contrast injection with a free-breathing 3D variable flip angle (VFA) GRASP-VIBE acquisition, which we validated with a breath-hold 2D Modified Look-Locker (MOLLI) sequence. A second MOLLI T1 map was obtained 10 minutes after contrast injection to compute extracellular volume fraction (ECV). During Gadolinium (1 mmol/kg @ 2 ml/s) contrast injection, continuous free-breathing compressed sensing GRASP-VIBE was obtained for 5 minutes and images were reconstructed following the Yarra framework (https://yarra-framework.org) at a temporal resolution of 3.3 s. The extended Toft’s model was used to compute pharmacokinetic parameters of the diaphragm19. Additionally, native 2D T2 mapping was performed with three T2 preparation times (0, 25 and 55 ms) and a bSFFP read-out. The protocol duration was approximately 40 minutes.

Results

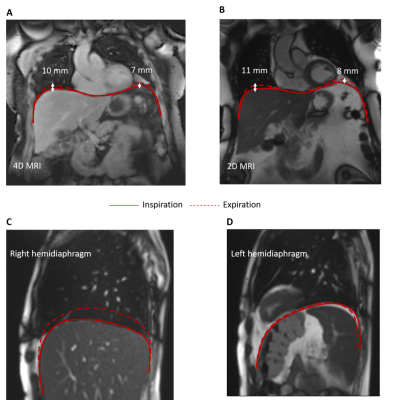

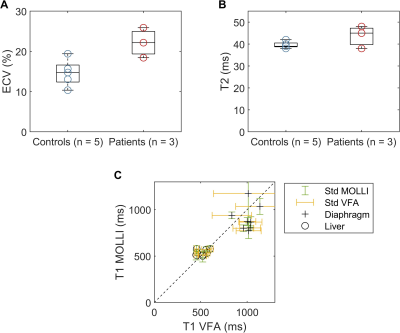

We successfully scanned the cine bSSFP and 4D joint MOCO-HDTV sequences. Diaphragmatic excursion measured with 2D+t and 4D imaging was similar (Figure 1A-B). Two out of three ICU patients showed a diminished motion of the diaphragm in one of the two hemidiaphragms (Figure 1C-D). The anterior diaphragm was well visible on the 2D T1 maps, VFA 3D T1 maps (Figure 2), T2 maps and on the contrast-enhanced acquisitions (Figure 3). T1 values of the liver and the diaphragm measured with the 3D VFA method (free-breathing) were in the same order of magnitude as measured with the MOLLI sequence (breath-hold), but the variation was larger when using the VFA method (Figure 4). Mean ECV (0.22 ± 0.03 vs. 0.15 ± 0.03) and T2 (44.0 ± 4.2 vs. 40.0 ± 1.4 ms) were higher in patients compared to controls (Figure 4).Discussion

We successfully assessed diaphragm motion in 4D fashion and compared results to a conventional 2D+t acquisition in one slice. To truly benefit from the 4D motion, 3D segmentation of the diaphragm should be used to fully study the complex motion of the diaphragm.To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to show that T1 mapping, T2 mapping, and DCE are feasible in the human diaphragm. Preliminary results suggest a trend towards increased ECV and T2 in the diaphragm of COVID-19 ICU patients, which is correlated with the amount of fibrosis (ECV) and oedema (T2) in tissues20. This fits the hypothesis of presence of fibrosis and/or inflammation due to COVID-19 infection and mechanical ventilation.

Taken together, this indicates that MRI can now be used to study diaphragm pathology.

Conclusion

We show that MRI of the diaphragm is feasible, even in critically ill patients recently liberated from mechanical ventilation. Imaging COVID-19 ICU patients can provide new insights in diaphragm weakness or injury and allow us to understand the pathophysiological mechanisms behind diaphragm weakness and the long-term consequences, while designing new treatment options.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a ZonMw Top grant.References

[1] S. K. Powers et al., "Mechanical ventilation results in progressive contractile dysfunction in the diaphragm," Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 92, no. 5, pp. 1851-1858, 2002/05/01 2002, doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00881.2001.

[2] S. Jaber et al., "Rapidly Progressive Diaphragmatic Weakness and Injury during Mechanical Ventilation in Humans," American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, vol. 183, no. 3, pp. 364-371, 2011, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0670OC.

[3] G. Hermans, A. Agten, D. Testelmans, M. Decramer, and G. Gayan-Ramirez, "Increased duration of mechanical ventilation is associated with decreased diaphragmatic force: a prospective observational study," (in eng), Critical care (London, England), vol. 14, no. 4, pp. R127-R127, 2010, doi: 10.1186/cc9094.

[4] G. S. Supinski and L. A. Callahan, "Diaphragm weakness in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients," Critical care (London, England), vol. 17, no. 3, pp. R120-R120, 2013, doi: 10.1186/cc12792.

[5] M. Dres et al., "Coexistence and Impact of Limb Muscle and Diaphragm Weakness at Time of Liberation from Mechanical Ventilation in Medical Intensive Care Unit Patients," American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, vol. 195, no. 1, pp. 57-66, 2016, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0367OC.

[6] P. E. Hooijman et al., "Diaphragm Muscle Fiber Weakness and Ubiquitin–Proteasome Activation in Critically Ill Patients," American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, vol. 191, no. 10, pp. 1126-1138, 2015/05/15 2015, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2214OC.

[7] E. C. Goligher et al., "Evolution of Diaphragm Thickness during Mechanical Ventilation. Impact of Inspiratory Effort," American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, vol. 192, no. 9, pp. 1080-1088, 2015/11/01 2015, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201503-0620OC.

[8] S. Levine et al., "Rapid Disuse Atrophy of Diaphragm Fibers in Mechanically Ventilated Humans," New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 358, no. 13, pp. 1327-1335, 2008/03/27 2008, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070447.

[9] E. C. Goligher et al., "Mechanical Ventilation–induced Diaphragm Atrophy Strongly Impacts Clinical Outcomes," American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, vol. 197, no. 2, pp. 204-213, 2017, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0536OC.

[10] A. Demoule et al., "Diaphragm Dysfunction on Admission to the Intensive Care Unit. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Prognostic Impact—A Prospective Study," American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, vol. 188, no. 2, pp. 213-219, 2013, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1668OC.

[11] Z. Shi et al., "Diaphragm Pathology in Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19 and Postmortem Findings From 3 Medical Centers," JAMA Internal Medicine, 2020, doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6278.

[12] Z. Shi et al., "COVID-19 is associated with distinct myopathic features in the diaphragm of critically ill patients," BMJ Open Respiratory Research, vol. 8, no. 1, p. e001052, 2021, doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2021-001052.

[13] Z. Shi et al., "Replacement Fibrosis in the Diaphragm of Mechanically Ventilated Critically Ill Patients," American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2022, doi: 10.1164/rccm.202208-1608LE.

[14] D. Jansen et al., "Positive end-expiratory pressure affects geometry and function of the human diaphragm," Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 131, no. 4, pp. 1328-1339, 2021/10/01 2021, doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00184.2021.

[15] K. Mogalle et al., "Quantification of Diaphragm Mechanics in Pompe Disease Using Dynamic 3D MRI," PloS one, vol. 11, pp. e0158912-e0158912, 2016, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158912.

[16] S. C. A. Wens et al., "Lung MRI and impairment of diaphragmatic function in Pompe disease," BMC Pulmonary Medicine, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 54, 2015/05/06 2015, doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0058-3.

[17] C. A. Bishop et al., "Semi-Automated Analysis of Diaphragmatic Motion with Dynamic Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Healthy Controls and Non-Ambulant Subjects with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy," (in eng), Frontiers in neurology, vol. 9, p. 9, 2018, doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00009.

[18] C. M. Rank et al., "4D respiratory motion-compensated image reconstruction of free-breathing radial MR data with very high undersampling," (in eng), Magn Reson Med, vol. 77, no. 3, pp. 1170-1183, Mar 2017, doi: 10.1002/mrm.26206.

[19] P. S. Tofts et al., "Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced t1-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: Standardized quantities and symbols," Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging,https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1522-2586(199909)10:3

[20] Margaret Cheng, H.-L., Stikov, N., Ghugre, N.R. and Wright, G.A. (2012), Practical medical applications of quantitative MR relaxometry. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 36: 805-824. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.23718

Figures