4644

Accelerating myelin water fraction imaging using compressed sensing and BMC-mcDESPOT1Laboratory of Clinical Investigations, National Institiute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Brain

We demonstrated the feasibility of compressed sensing (CS) to accelerate myelin water fraction (MWF) imaging using the BMC-mcDESPOT method. Our results showed that derived MWF maps using CS were similar to those derived without CS. Findings from this study indicate that whole brain, high resolution, MWF map can be derived within a few minutes.Introduction

Myelin water fraction (MWF) provides an MR imaging biomarker to investigate the myelination patterns in cerebral development and neurodegeneration (1-3). In previous work, we introduced the Bayesian Monte Carlo analysis of multicomponent-driven equilibrium single-component observation of and T1 and T2 (BMC-mcDESPOT ) method for whole-brain, high-resolution, MWF mapping within 20 min (4, 5). Despite this improvement in the temporal and spatial resolutions, as well as the wide applicability of BMC-mcDESPOT to study brain aging and dementia (1, 4-8), the acquisition time remains relatively long particularly for participants with a limited capability to remain still during the scan session. Therefore, any attempt to accelerate the scanning time would be beneficial for further integration of this technique in clinical investigations, especially those that involve acquisition of several other MR parameters or contrasts within the same scan session. Here, we investigated the feasibility of compressed sensing (CS) to accelerate the acquisition of the BMC-mcDESPOT images used to generate the corresponding MWF map. CS permits accelerating MRI acquisition by acquiring less data through under-sampling of the k-space while taking advantage of the sparsity of the MR images. This work was motivated by recent demonstrations of the applicability of CS to drastically reduce the acquisition time in quantitative MRI, including for MWF determination from multi-echo sequence (9).Methods

Data AcquisitionAll images presented here were acquired on a 3T Philips MRI system. In the Philips system, the CS has combined with the Sensitivity Encoding (SENSE) (10) method, used in parallel imaging, allowing a drastic reduction of the acquisition time (11, 12). To investigate the feasibility of CS-SENSE to accelerate MWF imaging, one participant has undergone our BMC-mcDESPOT protocol consisting of acquiring SPGR and bSSFP images at different flip angles. Details of this protocol can be found here (4-6). Three datasets were acquired without any CS acceleration leading to an acquisition time of ~21 min per dataset, while three other datasets were acquired with CS factor of 2 leading to an acquisition time of ~12 min per dataset. For all acquisitions, the SENSE factor was set to 2, as conventional.

Data Processing

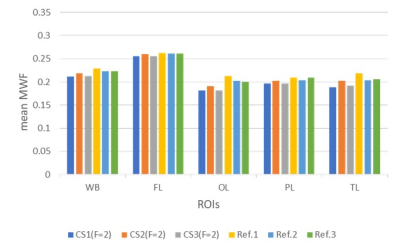

For each dataset, a whole-brain MWF map was generated using the BMC-mcDESPOT analysis (4, 5, 13), and then registered to the MNI space using FSL (14). Further, the mean MWF values were calculated in five white matter (WM) regions of interest (ROIs) defined from MNI, namely, the whole brain, frontal lobes, occipital lobes, parietal lobes, and temporal lobes.

Results and Discussion

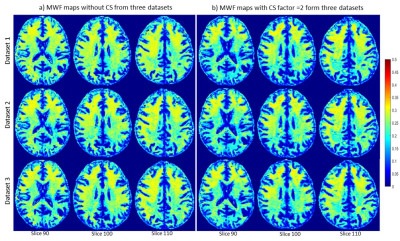

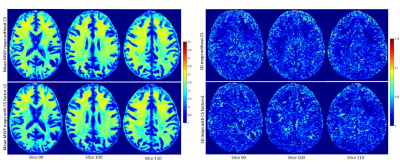

Figure 1 shows representative MWF maps calculated using the BMC-mcDESPOT analysis from imaging datasets acquired without CS (Fig. 1a) or with CS leading to an acceleration factor of 2 (Fig. 1b), each from three different datasets. Results are shown for three representative slices. Visual inspection indicates that derived maps using CS exhibit similar regional values as compared to the reference maps (i.e., without CS). This is markedly visible in the averaged MWF maps calculated over the three datasets (Fig. 2). Moreover, the standard deviation (SD) maps, calculated over the three datasets obtained with or without CS, exhibit low regional values, highlighting the great reproducibility of the BMC-mcDESPOT method including when CS with an acceleration factor of 2 is used. Further, our quantitative analysis of the mean MWF values calculated within the main WM brain structures agree with our visual observation indicating virtually identical values across all datasets acquired with or without CS (Fig. 3). These findings indicate that CS, especially the CS-SENSE technique, is reliable for myelin water imaging without losses in spatial resolution or signal-to-noise ratio, and open the way to explore the feasibility of this technique for further MWF mapping acceleration.Conclusions

A whole brain, high-resolution, MWF map can be derived using a combination of compressed sensing and BMC-mcDESPOT within 12 min.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.References

1. Bouhrara M, Reiter DA, Bergeron CM, Zukley LM, Ferrucci L, Resnick SM, et al. Evidence of demyelination in mild cognitive impairment and dementia using a direct and specific magnetic resonance imaging measure of myelin content. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2018;14(8):998-1004.

2. Dean III DC, Sojkova J, Hurley S, Kecskemeti S, Okonkwo O, Bendlin BB, et al. Alterations of myelin content in Parkinson’s disease: a cross-sectional neuroimaging study. PloS one. 2016;11(10):e0163774.

3. MacKay AL, Laule C. Magnetic resonance of myelin water: an in vivo marker for myelin. Brain plasticity. 2016;2(1):71-91.

4. Bouhrara M, Spencer RG. Improved determination of the myelin water fraction in human brain using magnetic resonance imaging through Bayesian analysis of mcDESPOT. Neuroimage. 2016;127:456-71.

5. Bouhrara M, Spencer RG. Rapid simultaneous high-resolution mapping of myelin water fraction and relaxation times in human brain using BMC-mcDESPOT. NeuroImage. 2017;147:800-11.

6. Bouhrara M, Rejimon AC, Cortina LE, Khattar N, Bergeron CM, Ferrucci L, et al. Adult brain aging investigated using BMC-mcDESPOT–based myelin water fraction imaging. Neurobiology of aging. 2020;85:131-9.

7. Dean DC, Hurley SA, Kecskemeti SR, O’Grady JP, Canda C, Davenport-Sis NJ, et al. Association of amyloid pathology with myelin alteration in preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA neurology. 2017;74(1):41-9.

8. Deoni SC. Correction of main and transmit magnetic field (B0 and B1) inhomogeneity effects in multicomponent‐driven equilibrium single‐pulse observation of T1 and T2. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2011;65(4):1021-35.

9. Chen HS, Majumdar A, Kozlowski P. Compressed sensing CPMG with group‐sparse reconstruction for myelin water imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2014;71(3):1166-71.

10. Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P. SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1999;42(5):952-62.

11. Geerts-Ossevoort L, de Weerdt E, Duijndam A, van IJperen G, Peeters H, Doneva M, et al. Speed done right. Every time. 2020.

12. Sartoretti T, Reischauer C, Sartoretti E, Binkert C, Najafi A, Sartoretti-Schefer S. Common artefacts encountered on images acquired with combined compressed sensing and SENSE. Insights into Imaging. 2018;9(6):1107-15.

13. Bouhrara M, Spencer RG. Incorporation of nonzero echo times in the SPGR and bSSFP signal models used in mcDESPOT. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2015;74(5):1227-35.

14. Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. Fsl. Neuroimage. 2012;62(2):782-90.

Figures