4627

Cramér-Rao Bound Optimized Linear Bases for Low-Rank Subspace Reconstruction

Andrew Mao1,2,3, Sebastian Flassbeck1,2, Cem Gultekin4, and Jakob Asslaender1,2

1Center for Biomedical Imaging, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 3Vilcek Institute of Graduate Biomedical Sciences, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 4Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York University, New York, NY, United States

1Center for Biomedical Imaging, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 3Vilcek Institute of Graduate Biomedical Sciences, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 4Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York University, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Sparse & Low-Rank Models, Magnetization transfer, MR Fingerprinting, Hybrid State, Cramer-Rao bound, Quantitative Imaging, Low-Rank Reconstruction

This works extends the traditional framework for estimating low-rank bases that maximize preserved signal energy to additionally preserve the Cramér-Rao bound of the biophysical parameters in quantitative imaging. To this end, we orthogonalize the signal's derivatives wrt. the model parameters and incorporate them into the basis estimation process. We demonstrate in silico an improvement in the Cramér-Rao bound of all biophysical parameters with negligible cost to signal energy preservation, which translates to improved image quality and SNR in vivo.Introduction

Low-rank subspace reconstruction, e.g., using the singular value decomposition (SVD) of a simulated dictionary of signals, is increasingly used to reconstruct time series of MR images.1,2,3 In quantitative MRI, and particularly in MR Fingerprinting,4 image reconstruction is only an intermediate step to obtaining quantitative parameter maps. By construction, the linear subspace obtained by the SVD maximizes the preserved signal energy, but may be suboptimal in terms of noise in the parameter maps, e.g., as measured by the Cramér-Rao lower bound (CRB).5 In this work, we optimize linear bases to preserve the CRB of the biophysical parameters in addition to the signal energy.Theory

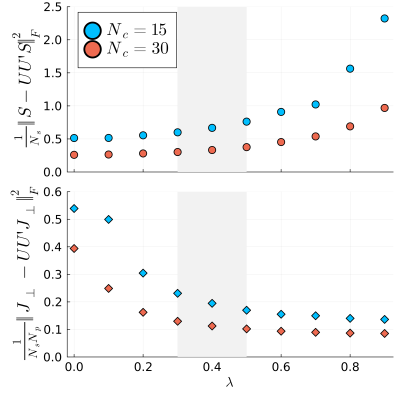

For Gaussian noise, the CRB can be calculated from the diagonal entries of the inverse Fisher Information Matrix $$$F^{-1}=(J'J)^{-1}$$$, where $$$J$$$ is the Jacobian matrix whose columns are the signal's derivatives with respect to the model parameters. Using the CRB's geometric interpretation,6 one can show that a parameter's CRB is also equal to the inverse squared norm of its orthogonalized derivative, i.e., the derivative minus the parallel components of the derivatives wrt. all other model parameters. To preserve the CRB, we optimize a linear basis $$$U$$$ that preserves the energy of the orthogonalized derivatives according to the objective: $$\underset{U}{\mathrm{arg\,min}}~(1-\lambda)\big\|S-UU'S\big\|^2_F+\lambda\big\|J_\perp-UU'J_\perp\big\|^2_F$$ where the compression matrix $$$U \in \mathbb{R}^{N_T\times N_c}$$$ has $$$N_T$$$ time points and $$$N_c$$$ coefficients, $$$S \in \mathbb{C}^{N_T\times N_s}$$$ is the dictionary with $$$N_s$$$ fingerprints, $$$J_{\perp} \in \mathbb{C}^{N_T\times N_sN_p}$$$ is the matrix of $$$N_p$$$ orthogonalized derivatives of interest, $$$'$$$ denotes the conjugate transpose and $$$_F$$$ denotes the Frobenius norm. $$$\lambda \in [0,1]$$$ controls the convex combination of the signal energy loss (first term) and CRB loss (second term) in the overall cost. Note that this equation reduces to the familiar sample PCA problem for $$$\lambda=0$$$, whose solution is given by the SVD of the dictionary $$$S$$$ (``traditional SVD").7 The two terms can be combined and solved by performing an SVD of the horizontally concatenated matrix $$$\tilde{S}\triangleq\begin{bmatrix}(1-\lambda)S&\lambda J_{\perp}\end{bmatrix}$$$ (``CRB-SVD").Methods

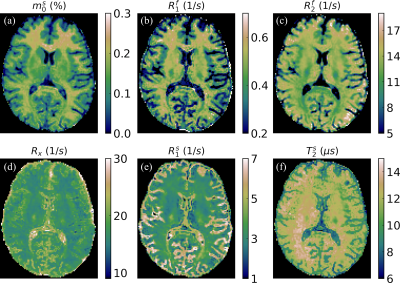

We demonstrate our approach with quantitative magnetization transfer (qMT) imaging. The two-pool model, shown in Fig1,8,9,10 includes 9 derivatives (a scaling factor $$$M_0$$$, the fractional semi-solid spin-pool size $$$m_0^s$$$, the free spin-pool relaxation rates $$$R_1^f,R_2^f$$$, the exchange rate $$$R_x$$$, the semi-solid spin-pool relaxation rates/times $$$R_1^s,T_2^s$$$, and the field inhomogeneities $$$B_0$$$ and $$$B_1^+$$$). We simulated a dictionary of $$$\approx600$$$k fingerprints using qMT parameter values typically found in brain tissue,10,11 where $$$2/3$$$ are used for basis estimation and $$$1/3$$$ for testing. Orthogonalized derivatives for 6 parameters of interest ($$$m_0^s,R_1^f,R_2^f,R_x,R_1^s,T_2^s$$$) were computed using QR factorization to form the matrix $$$\tilde{S}$$$. We computed the SVD for 10 evenly-spaced values $$$\lambda\in[0,1]$$$.We scanned a healthy subject on a 3T Biograph mMR (Siemens, Germany) scanner using a 12min CRB-optimized hybrid-state sequence12,13,14 at 1.6mm isotropic resolution with a 3D golden-angle radial koosh-ball trajectory.15 For various combinations of $$$\{\lambda,N_c\}$$$, we reconstructed subspace coefficient images with a fixed locally low-rank penalty strength using FISTA in Julia.16 Parameter maps are fitted with a neural network trained to approximate an unbiased estimator for each combination of $$$\{\lambda,N_c\}$$$ using the strategy described in Ref. [17].

Results and Discussion

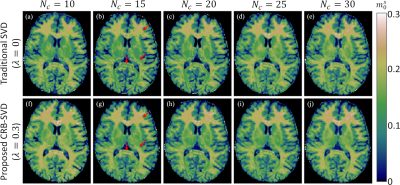

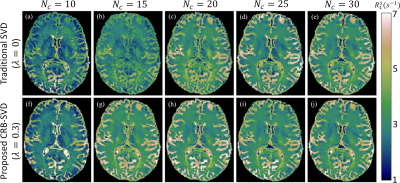

Fig2 plots the test data-set's mean signal energy and CRB losses as a function of $$$\lambda$$$ for $$$N_c=15$$$ and $$$N_c=30$$$. As expected, we observe improved CRB preservation and degraded signal energy preservation with increasing $$$\lambda$$$, but at $$$\lambda=0.3$$$ we observe a substantially improved CRB relative to the traditional SVD ($$$\lambda=0$$$) at almost no cost in the preserved energy. For $$$N_c=15$$$, the mean improvement in CRB at $$$\lambda=0.3$$$ was $$$\approx$$$80%. This CRB gain is generally more pronounced at small $$$N_c$$$, and at $$$N_c\gg15$$$ the two losses tend to converge over all $$$\lambda$$$.The $$$m_0^s$$$-maps depicted in Fig3 are largely consistent between all bases, but we do observe the anticipated SNR improvement with the CRB-SVD compared to the traditional SVD, most prominently for small $$$N_c$$$ (red arrows). The maps of the generally worse-conditioned $$$R_1^s$$$ parameter reveal even more pronounced image alterations at small $$$N_c$$$ when using the traditional SVD (Fig4). In contrast, the CRB-SVD is able to maintain more consistent image quality with small $$$N_c$$$. This pattern can also be observed for $$$R_x$$$ and $$$T_2^s$$$ (not shown). Consistent with Ref. [6], these results suggest that performing the SVD on the signals alone is suboptimal in preserving the CRB, which depends on preserving the orthogonal components of the derivatives. Our proposed method offers either improved SNR at the same $$$N_c$$$ with almost no cost, or the ability to reduce $$$N_c$$$ while retaining the same image quality---yielding substantial savings in reconstruction time and memory requirements, which can be limiting for non-Cartesian 4D+ applications. Fig5 shows all biophysical parameter maps of the 2-pool qMT model at $$$\{\lambda=0.3,N_c=15\}$$$.

One limitation of this work is the memory requirements for the SVD (700GB here), which scale linearly with the number of included orthogonalized derivatives. Our sample size was dictated by these practical limitations, though comparison to the traditional SVD with 5x the sample size yielded virtually no improvements. Future work will include more memory efficient algorithms for performing large-scale SVD, as well as application of the method to a more noise-dominated use case.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R21 EB027241, F30 AG077794, T32 GM136573, and performed under the rubric of the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R), an NIBIB National Center for Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIH P41 EB017183).References

- McGivney, D. F., Pierre, E., Ma, D., Jiang, Y., Saybasili, H., Gulani, V., & Griswold, M. A. (2014). SVD compression for magnetic resonance fingerprinting in the time domain. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 33(12), 2311–2322. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2014.2337321

- Tamir, J. I., Uecker, M., Chen, W., Lai, P., Alley, M. T., Vasanawala, S. S., & Lustig, M. (2017). T 2 shuffling: Sharp, multicontrast, volumetric fast spin‐echo imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 77(1), 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26102

- Assländer, J., Cloos, M. A., Knoll, F., Sodickson, D. K., Hennig, J., & Lattanzi, R. (2018). Low rank alternating direction method of multipliers reconstruction for MR fingerprinting. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 79(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26639

- Ma, D., Gulani, V., Seiberlich, N., Liu, K., Sunshine, J. L., Duerk, J. L., & Griswold, M. A. (2013). Magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Nature, 495(7440), 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11971

- Cramér H. Mathematical Methods of Statistics. Princeton University Press; 1946.

- Scharf, L. L., & McWhorter, L. T. (1993). Geometry of the Cramér-Rao bound. Signal Processing, 31(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1684(93)90088-R

- Vidal R, Ma Y, Sastry SS. Generalized Principal Component Analysis. Springer New York; 2016.

- Henkelman, R. M., Huang, X., Xiang, Q. ‐S, Stanisz, G. J., Swanson, S. D., & Bronskill, M. J. (1993). Quantitative interpretation of magnetization transfer. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 29(6), 759–766. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1910290607

- Helms, G., & Hagberg, G. E. (2009). In vivo quantification of the bound pool T1 in human white matter using the binary spin-bath model of progressive magnetization transfer saturation. Physics in Medicine and Biology, 54(23). https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/54/23/N01

- Assländer, J., Gultekin, C., Flassbeck, S., Glaser, S. J., & Sodickson, D. K. (2021). Generalized Bloch model: A theory for pulsed magnetization transfer. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, (July), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.29071

- Bojorquez, J. Z., Bricq, S., Acquitter, C., Brunotte, F., Walker, P. M., & Lalande, A. (2017). What are normal relaxation times of tissues at 3 T? Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 35, 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2016.08.021

- Assländer, J., Novikov, D. S., Lattanzi, R., Sodickson, D. K., & Cloos, M. A. (2019). Hybrid-state free precession in nuclear magnetic resonance. Communications Physics, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0174-0

- Assländer, J., Lattanzi, R., Sodickson, D. K., & Cloos, M. A. (2019). Optimized quantification of spin relaxation times in the hybrid state. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 82(4), 1385–1397. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.27819

- Flassbeck, S., & Assländer, J. (2022). Quantitative magnetization transfer: Estimation of the Semi-Solid Spin Pool’s T1. Proceedings of the 30th Annual Meeting of ISMRM.

- Chan, R. W., Ramsay, E. A., Cunningham, C. H., & Plewes, D. B. (2009). Temporal stability of adaptive 3D radial MRI using multidimensional golden means. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 61(2), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.21837

- Knopp, T., & Grosser, M. (2021). MRIReco.jl: An MRI Reconstruction Framework written in Julia. 1–24. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/2101.12624

- Zhang, X., Duchemin, Q., Liu*, K., Gultekin, C., Flassbeck, S., Fernandez‐Granda, C., & Assländer, J. (2022). Cramér–Rao bound‐informed training of neural networks for quantitative MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 88(1), 436–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.29206

Figures

Fig1. (a) As explained in Ref. [6], distinguishing one model parameter, e.g., m0s, from another parameter, e.g., R1f, depends on the components of its signal derivative that are orthogonal to the derivative w.r.t. R1f. (b) Depiction of the signal s, its derivative ds/dm0s, and the orthogonalized derivative (ds/dm0s)$$$\perp$$$, where the components parallel to all other signal derivatives were removed. In this work, we optimize bases that maximize the energy of both s and (ds/dm0s)$$$\perp$$$ to preserve the signal and CRB respectively.

Fig2. Signal energy (top) and orthogonalized derivative energy loss (bottom) averaged over the test dataset of simulated signal evolutions. Note that the latter is equal to 1/CRBtime-1/CRBcompressed. With increasing λ, the CRB is improved with some cost to the preserved energy. λ$$$\in$$$[0.3,0.5] (shaded grey area), however, yields nearly the maximal improvement in the CRB with negligible differences in preserved energy for both Nc values.

Fig3. Comparison of the semi-solid spin pool's fractional size m0s extracted from a traditional SVD basis (λ=0) (a-e) and proposed CRB-SVD basis (λ=0.3) (f-j) for different numbers of coefficients (Nc). Each panel is reconstructed separately and fitted with a neural network.17 The m0s maps appear fairly similar throughout except for Nc=10, which is close to the theoretical floor of 9, the number of model parameters. As expected, the SNR is improved with the CRB-SVD versus traditional SVD basis, especially for Nc=15 (red arrows).

Fig4. Comparison of the semi-solid spin pool's longitudinal relaxation rate R1s extracted from a traditional SVD basis (λ=0) (a-e) and proposed CRB-SVD basis (λ=0.3) (f-j) for different numbers of coefficients. With the traditional SVD basis, the increasing CRB of R1s for small Nc results in image degradation (a,b), but the image quality is more consistent for Nc≥15 with the CRB-SVD basis (g-j).

Fig5. Quantitative magnetization transfer maps in an axial slice (1.6mm isotropic) for the basis corresponding to {λ=0.3,Nc=15}. With the traditional SVD basis, similar image quality would require Nc≥20. This reduction in Nc reduces the memory requirements, which is crucial for reconstructions of higher resolution data, e.g., 1mm isotropic.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4627