4617

Fast and robust parallel imaging algorithm for Spiral MRI with Fat-Water separation1Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Parallel Imaging, Parallel Imaging

Three different models to reconstruct fat and water spiral images with parallel acquisition are compared in terms of computational efficiency and reconstruction quality. The best reconstruction is obtained with a full model requiring the most computational time, while the model with the fastest computational time results in some degradation of image quality. A third, preferred model preserves most of the image quality of the first model, with nearly the same speedup as the latter model.Introduction

Spiral MRI offers high temporal efficiency and high SNR efficiency, especially when a long readout window is used1. However, this long acquisition window introduces blurring artifact in the presence of off-resonance and chemical shift 2,3. Previous work for removing this blur from Spiral images has been successfully applied to simultaneous separation of fat and water signals while maintaining SNR3.Parallel imaging algorithms such as SENSE are commonly used to shorten exam time. Utilization of SENSE on Spiral MRI has been investigated to improve temporal efficiency4. While the inclusion of fat/water separation and deblurring to the SENSE algorithm in Spiral imaging is feasible, the reconstruction time becomes longer due to the repetitive operations of blurring and deblurring in the conjugate gradient solver. The present work investigated two different approximations to the original full model for reconstructing SENSE with fat and water Spiral imaging, with the goal of discovering a robust approach to achieve accurate reconstruction with efficient computation.

Materials and Methods

Three models based on reference (3) were investigated and compared in terms of computational efficiency and data accuracy. The first model is the full model for Spiral imaging taking chemical shift, off-resonance, and multiple coils into account, for which the coil images $$$S_j$$$ are expressed by:$$\text{Model 1: }S_j(\overrightarrow{r}, TE) =\sum_{i=w,f}X_i(TE)\otimes\Phi(\overrightarrow{r},TE)\otimes(C_j(\overrightarrow{r})\rho (\overrightarrow{r})),$$

where $$$X_i$$$ represents the modulation of the average frequency including chemical shifts of the entire imaged slice, $$$\Phi$$$ the regionalized location dependent blurring kernel, $$$C_j$$$ the coil sensitivity of the j-th coil, and $$$\rho_i$$$ the fat and water component images. This model splits the blurring operations into a spatial invariant $$$X_i$$$ , which can be efficiently achieved via Fourier Transform, and a spatially varying $$$\Phi$$$, which requires computationally intensive convolution. One can expect that the sensitivity encoding can be performed after the blurring operation if the coil sensitivity map is spatially smooth. Models 2 and 3 relocate the blurring operators prior to the sensitivity encoding to reduce the number of blurring operations as follows:

$$\text{Model 2: }S_j(\overrightarrow{r}, TE) =\sum_{i=w,f}C_j(\overrightarrow{r}) (X_i(TE)\otimes\Phi(\overrightarrow{r},TE)\otimes\rho (\overrightarrow{r})), and $$

$$\text{Model 3: }S_j(\overrightarrow{r}, TE) =\sum_{i=w,f} X_i(TE)\otimes (C_j(\overrightarrow{r})(\Phi(\overrightarrow{r},TE)\otimes\rho (\overrightarrow{r}))). $$

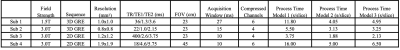

Model 2 simplifies the process by performing both mean frequency modulation and regionalized blurring before sensitivity encoding, while Model 3 only allows the regional blurring operation to be done before the coil encoding. A summary of the models is listed in Fig 1.

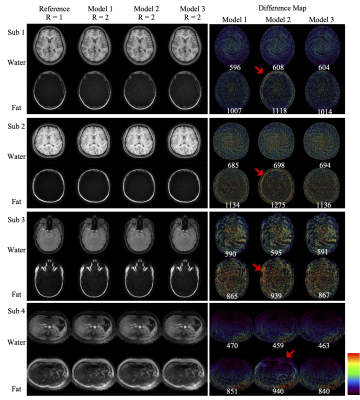

One volunteer was scanned on a 1.5T scanner (Philips Ambition X) and three volunteers on a 3.0T scanner (Philips Elition X). Coil compression based on singular value decomposition5 was applied to reduce computational complexities in the reconstruction and the number of virtual coils is listed along with other experimental settings in Table 1. Two-fold retrospective undersampling was performed to simulate parallel imaging acquisition on the fully sampled dataset, used as the reference to determine the artifact level of the reconstructed images. The reconstruction program was executed with Python based GPI platform6 on an Intel i-9 6 Core 2.9GHz system. The average reconstruction time per slice is included in Table 1.

Results

Table 1 shows that Model 1 took the longest to reconstruct the images and Model 2 the shortest, around two to three times faster than Model 1 among the demonstrated cases. Model 3 took only slightly longer than Model 2 (by 10% to 30%), as the majority of the computation involves the local spatially varying blurring operation. Fig 2. demonstrates all the cases and the difference map between each reconstruction and the reference. The reconstructed water images show little variation among different models which can also be noticed in the difference images and the corresponding root-mean-square error. However, consistently larger differences of the reconstructions using Model 2 are found in the fat channel regardless of the scanner’s hardware or contrast settings. On the other hand, Model 3’s fat images can achieve similar quality to Model 1. Therefore, Model 3 represents a strong option among these three in terms of computational efficiency and reconstruction accuracy.Discussion and Conclusion:

The present work compares three different models for a parallel imaging strategy to reconstruct fat and water images with spiral trajectories. The results suggest that coil-by-coil frequency modulation for the whole image, especially the fat channel, plays the most critical role in the reconstruction accuracy as the fat blurs to a much larger extent than the water. The residual, spatially varying blurring, which is more computationally intensive, is also more localized and less sensitive to the inaccuracy of the coil sensitivity, allowing the use of a simplified combined-coil operation to reduce computational complexity. Therefore, an attractive approach to reconstruct SENSE imaging with Spiral trajectories in the presence of fat and water is the Model 3 in the present work.Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Royal Philips.References

1. Ahn CB, Kim JH, Cho ZH. High-speed spiral-scan echo planar NMR imaging-I. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1986;5(1):2-7.

2. Delattre BM, Heidemann RM, Crowe LA, Vallee JP, Hyacinthe JN. Spiral demystified. Magn Reson Imaging. Jul 2010;28(6):862-81. doi:10.1016/j.mri.2010.03.036

3. Wang D, Zwart NR, Pipe JG. Joint water-fat separation and deblurring for spiral imaging. Magn Reson Med. Jun 2018;79(6):3218-3228.

4. Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Bornert P, Boesiger P. Advances in sensitivity encoding with arbitrary k-space trajectories. Magn Reson Med. Oct 2001;46(4):638-51.

5. Buehrer M, Pruessmann KP, Boesiger P, Kozerke S. Array compression for MRI with large coil arrays. Magn Reson Med. Jun 2007;57(6):1131-9.

6. Zwart NR, Pipe JG. Graphical programming interface: A development environment for MRI methods. Magn Reson Med. Nov 2015;74(5):1449-60.

Figures