4608

Toward an accurate MR measure of the axon radii by accounting for myelin-specific attenuation of the diffusion MRI signal in the brain

Stefania Oliviero1, Cosimo Del Gratta1, Andrada Costantina Traeba2, Tommaso Boccato3, Caterina Mainero2, and Nicola Toschi2,3

1Neuroscience, Imaging and Clinical Sciences, and Institute for Advanced Biomedical Technologies, University of Chieti-Pescara G. D'Annunzio, Chieti, Italy, 2A.A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 3Biomedicine and Prevention, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy

1Neuroscience, Imaging and Clinical Sciences, and Institute for Advanced Biomedical Technologies, University of Chieti-Pescara G. D'Annunzio, Chieti, Italy, 2A.A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 3Biomedicine and Prevention, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy

Synopsis

Keywords: Signal Modeling, White Matter, myelin, diffusion, in silico, MR

An accurate, noninvasive measure of axonal radii could play a crucial role in the understanding of healthy and diseased neural processes. Several diffusion-weighted MRI (dMRI) methods report on the axon radii distribution or mean axon radii. However, these measurements systematically overestimate histologically derived values. In this preliminary study, we address this limitation by formulating a model which explicitly includes the myelin contribution to the cerebral dMR signal. In detail, we introduce a myelinic compartment in both the AxCaliber and ActiveAx models and demonstrate a significant improvement of axonal radius estimation using synthetic data simulation.INTRODUCTION

Non-invasive measures of the axon radii distribution in the human brain could play a crucial role in basic, clinical, and potentially diagnostic research. Various pathologies and neurodevelopmental disorders involve size-selective neuronal changes or altered distribution of axon radii1-4. For example, in MS lesions, small-radius axons are preferentially susceptible to injury5-7. Diffusion-weighted MRI (dMRI) methods (e.g. AxCaliber8, and ActiveAx9) can extract microstructural features such as mean axon radius or the distribution of the axon radii within a voxel. However, the dMRI-derived axon radii distribution systematically overestimates the histologically derived values10-15. Discrepancies between histology and dMRI-derived axon radii have been ascribed to various confounding factors10,12,13,16-20 as well as the orientation dispersion21,22 and represent a crucial open problem in dMRI measurements. In this paper we propose additions to the AxCaliber and ActiveAx models, respectively, that explicitly include the myelin contribution to the dMR signal attenuation, and demonstrate in-silico that this improves the accuracy of the axonal radii estimation. Proof of concept on one human subject confirms that our model yields lower and more realistic estimations of axonal radii.METHODS

We synthesized five WM voxels from a numeric model of white matter WM23 including parallel myelinated and permeable axons while varying the percentage of axonal loss (0%, 15%, 30%, 70%, 90%), and, consequently, the axonal radii distribution and mean radius (the axonal loss simulation implements size-selective loss of the small-radius axons). We then performed a Monte Carlo simulation and calculated the dMR signals using an acquisition protocol developed and used for in-vivo AxCaliber dMRI acquisitions (gmax = 278 mT/m; three values for Δ combined with two b-values for a total of 273 acquisitions). We used the MDT tool24 to fit four different compartment models, i.e. AxCaliber, ActiveAx, AxCaliber_withMyelin, and ActiveAx_withMyelin. These models factor the total dMR brain signal (STOT) into compartmental contributions (I)$$ STOT=∑i wi·Si

Where wi is the fraction of the voxel volume occupied by compartment i and Si is the corresponding model of the dMRI signal. For the AxCaliber and ActiveAx models, the following compartments contribute to STOT:

- intra-axonal space characterized by a spatial distribution of parallel cylinders (the axons) with gamma-distributed radii (AxCaliber) or with the same radius (ActiveAx) and a non-Gaussian and anisotropic PDF of the water molecule displacements (Van Gelderen model25,26);

- extra-cellular space characterized by a so-called hindered diffusivity, with a Gaussian and anisotropic PDF of the water molecule displacements (tensor model27 in AxCaliber and zeppelin model27 in ActiveAx);

- cerebrospinal fluid - CSF (only in ActiveAx) with free and isotropic diffusion: in this case, the PDF of the water molecule displacements is Gaussian and isotropic with a diffusion coefficient D equal to that of free water, for each direction (ball model27).

$$ STOT=exp(-TE / T2o)·∑i wi·Si + exp(-TE / T2m)·wm·Sm

where TE is the eco time and the compartment m represents the myelin. The relaxation times T2o= 78 ms and T2m=15 ms were set according to Whittall et al.28. As proof of concept, we use our diffusion models to fit in-vivo on the dMR brain signal of one human subject, where the acquisition protocol is the same as the one used in the simulation.

RESULTS

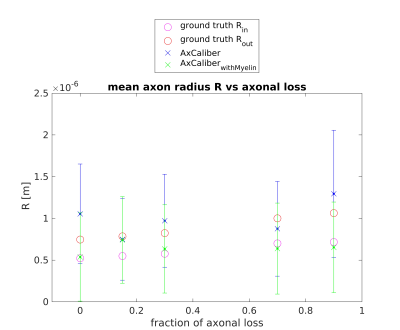

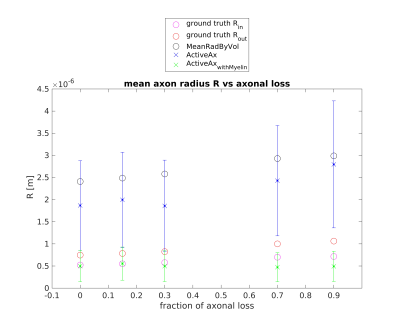

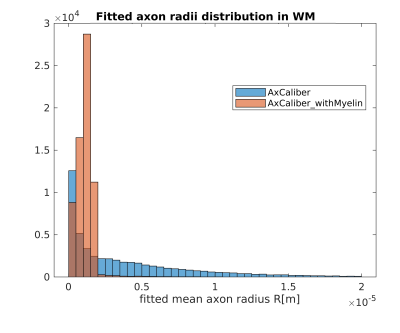

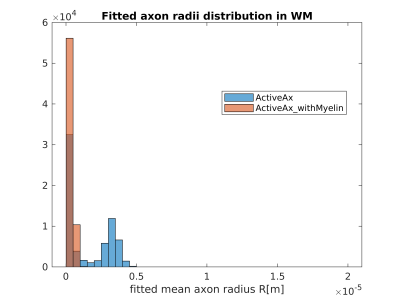

Figures 1 and 2 show the results obtained in simulation and, particularly, the comparison between the axonal radii estimated with and without taking into account the myelinic contribution to the dMR signal. The dMR-derived axonal radii systematically overestimate ground truth values in both models. This effect is strongly mitigated when including the myelinic compartment in the model. Figures 3 and 4 show the axon radii distributions estimated in-vivo (in the white matter WM of a volunteer). In accordance with the simulation results, dMR-derived axon radii estimated in-vivo are lower when taking into account the myelin contribution to the dMR signal. Finally, Figure 5 is a visual representation of the mean axonal radius obtained in-vivo using AxCaliber and ActiveAx with or without the myelin compartment.DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In the literature, the myelinic contribution to the dMR signal coming from the brain tissue is generally neglected, due to shorter myelinic T2 relaxation time, assuming that it is much smaller than the bulk signal coming from the intra- and extra-cellular spaces29,30. However, we found that adding a myelin compartment to the classical compartment models greatly improves their axon radius estimation. In agreement with some recent works23,31, our results suggest that myelin is not completely invisible to the dMR signal. Rather, taking into account its contribution could play a crucial role when very high accuracy is required in measuring the microstructural features of the brain tissue and, particularly, the axon radii.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Kjellstro¨m C, Conradi NG. Decreased axonal calibres without axonal loss in optic nerve following chronic alcohol feeding in adult rats: a morphometric study. Acta Neuropathologica. 1993; 85:117–121

- Wegiel J, Kaczmarski W, Flory M, Martinez-Cerdeno V, Wisniewski T, Nowicki K, Kuchna I, Wegiel J. Deficit of corpus callosum axons, reduced axon diameter and decreased area are markers of abnormal development of interhemispheric connections in autistic subjects. Acta Neuropathologica Communications. 2018; 6:143

- Zikopoulos B, Barbas H. Changes in prefrontal axons may disrupt the network in autism. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010; 30(44), 14595–14609

- Judson MC, Burette AC, Thaxton CL, Pribisko AL, Shen MD, Rumple AM, Philpot BD. Decreased Axon Caliber Underlies Loss of Fiber Tract Integrity, Disproportional Reductions in White Matter Volume, and Microcephaly in Angelman Syndrome Model Mice. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2017;37(31), 7347–7361

- Lassmann H. Axonal and neuronal pathology in multiple sclerosis: what have we learnt from animal models. Exp Neurol. 2010;225:2–8

- Ganter P, Prince C, Esiri MM. Spinal cord axonal loss in multiple sclerosis: a post-mortem study. Neuropathol Appl. 1999 Neurobiol 25:459–467

- Evangelou N, Konz D, Esiri MM, Smith S, Palace J, Matthews PM. Size-selective neuronal changes in the anterior optic pathways suggest a differential susceptibility to injury in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2001;124:1813–1820

- Assaf Y, Blumenfeld Katzir T, Yovel Y, Basser PJ. AxCaliber: a method for measuring axon diameter distribution from diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:1347–1354

- Alexander DC, Hubbard PL, Hall MG, Moore EA, Ptito M, Parker GJ, Dyrby TB. Orientationally invariant indices of axon diameter and density from diffusion MRI. NeuroImage. 2010; 52(4), 1374–1389

- Zhang H, Hubbard PL, Parker GJM, Alexander DC. Axon diameter mapping in the presence of orientation dispersion with diffusion MRI. NeuroImage. 2011; 56:1301–1315

- Burcaw LM, Fieremans E, Novikov DS. Mesoscopic structure of neuronal tracts from time-dependent diffusion. NeuroImage. 2015; 114, 18–37

- Horowitz A, Barazany D, Tavor I, Bernstein M, Yovel G, Assaf Y. In vivo correlation between axon diameter and conduction velocity in the human brain. Brain Structure and Function. 2015; 220(3), 1777–1788

- Innocenti GM, Caminiti R, Aboitiz F. Comments on the paper by Horowitz et al. (2014). Brain Structure and Function. 2015; 220(3), 1789–1790

- Lee HH, Fieremans E, Novikov DS. What dominates the time dependence of diffusion transverse to axons: Intra-or extraaxonal water? NeuroImage. 2018; 182, 500–510

- Lee HH, Jespersen SN, Fieremans E, Novikov DS. The impact of realistic axonal shape on axon diameter estimation using diffusion MRI. NeuroImage. 2020; 223, 117228

- Nilsson M, Lasicˇ S, Drobnjak I, Topgaard D, Westin CF. Resolution limit of cylinder diameter estimation by diffusion MRI: The impact of gradient waveform and orientation dispersion. NMR in Biomedicine. 2017; 30(7), e3711

- Fieremans E, Burcaw LM, Lee H-H, Lemberskiy G, Veraart J, Novikov DS. In vivo observation and biophysical interpretation of time-dependent diffusion in human white matter. NeuroImage. 2016;129:414–427

- Barazany D, Basser PJ, Assaf Y. In vivo measurement of axon diameter distribution in the corpus callosum of rat brain. Brain. 2009;132:1210–1220. Aboitiz F, Scheibel AB, Fisher RS, Zaidel E. Fiber composition of the human corpus callosum. Brain Research. 1992;598:143–153

- van Gelderen P, Des Pres D, van Zijl PCM, Moonen CTW. Evaluation of restricted diffusion in cylinders. Phosphocreatine in rabbit leg muscle. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1994; Series B 103:255–260

- Neuman CH. Spin Echo of spins diffusing in a bounded medium. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1974;60:4508–4511

- Drobnjak I, Zhang H, Ianus¸ A, Kaden E, Alexander DC. PGSE, OGSE, and sensitivity to axon diameter in diffusion MRI: insight from a simulation study. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016;75:688–700

- Nilsson M, La¨ tt J, Sta° hlberg F, Westen D, Hagsla¨ tt H. The importance of axonal undulation in diffusion MR measurements: a monte carlo simulation study. NMR in Biomedicine. 2012;25:795–805

- Oliviero S, Del Gratta C. Impact of the acquisition protocol on the sensitivity to demyelination and axonal loss of clinically feasible DWI techniques: a simulation study. MAGMA. 2021;34(4):523-543

- Harms RL, Fritz FJ, Tobisch A, Goebel R, Roebroeck A. Robust and fast nonlinear optimization of diffusion MRI microstructure models. Neuroimage. 2017; 15;155:82-96

- van Gelderen P, DesPres D, van Zijl PC, Moonen CT. Evaluation of restricted diffusion in cylinders. Phosphocreatine in rabbit leg muscle. J Magn Reson B. 1994;103(3):255-60

- Wang LZ, Caprihan A, Fukushima E. The narrow-pulse criterion for pulsed-gradient spin-echo diffusion measurements. JMagnResonSerA. 1995;117(2):209-219

- Panagiotaki E, Schneider T, Siow B, Hall MG, Lythgoe MF, Alexander DC. Compartment models of the diffusion MR signal in brain white matter: A taxonomy and comparison. NeuroImage. 2012;59(3), 2241-2254

- Whittall KP, MacKay AL, Graeb DA, Nugent RA, Li DK, Paty DW. In vivo measurement of T2 distributions and water contents in normal human brain. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37(1):34-43

- Stikov N, Campbell JSW, Stroh T, Lavelée M, Frey S, Novek J et al. In vivo histology of the myelin g-ratio with magnetic resonance imaging. NeuroImage. 2015;118:397–405

- Wu Y, Alexander AL, Fleming JO et al. Myelin water fraction in human cervical spinal cord in vivo. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:304–306

- Grussu F, Schneider T, Tur C, Yates RL et al. Neurite dispersion: a new marker of multiple sclerosis spinal cord pathology? Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017;4(9):663–679

Figures

Figure 1. dMR-derived mean axon radius obtained in five synthetic voxels of WM with different fractions of axonal loss (with respect to the healthy axon distribution) by using the AxCaliber model encompassing or not the myelin compartment. A Rician noise with SNR = 20 affects the synthetic dMR signals. Red and magenta circles represent the ground truth values of the axon radius with or without the myelin sheet (respectively Rout and Rin).

Figure 2. dMR-derived mean axon radius obtained in five synthetic voxels of WM with different fractions of axonal loss (with respect to the healthy axon distribution) by using the ActiveAx model encompassing or not the myelin compartment. A Rician noise with SNR = 20 affects the synthetic dMR signals. Red and magenta circles represent the ground truth values of the axon radius with or without the myelin sheet (respectively Rout and Rin). Black circles represent the mean axon radius by volume9.

Figure 3. Histograms of the dMR-derived axon radii distribution obtained in-vivo in the WM of a volunteer, by using the AxCaliber model with or without the myelinic compartment.

Figure 4. Histograms of the dMR-derived axon radii distribution obtained in-vivo in the WM of a volunteer, by using the ActiveAx model with or without the myelinic compartment.

Figure 5. Visual representation of the mean axonal radius maps obtained in-vivo in a human subject, using AxCaliber and ActiveAx with or without the myelin compartment.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4608