4596

EPG-based optimization of the SNR of the phase-cycled bSSFP in phase-based electrical conductivity mapping1ICube, Université de Strasbourg-CNRS, Strasbourg, France

Synopsis

Keywords: Signal Modeling, Simulations

Phase-based electrical conductivity mapping requires high SNR due to the instability of the reconstruction. Electrical conductivity can be measured by the phase-cycled bSSFP, a high-SNR sequence which is also weighted by other biophysical parameters but for which no complete analytical model exist. In this work, we use EPG-based simulations to investigate how the bSSFP signal varies with the flip angle, the phase step and the pulse duration in a diffusive, two-pools model of the brain white matter at 3 T. We show that our simulations agree with in-vivo acquisitions and establish guidelines to optimize the SNR of the phase-cycled bSSFP.Introduction

Electrical conductivity can be measured by the Laplacian of the B1 phase [1]. However, numerical approximations of the Laplacian operator are sensitive to noise, and thus required high SNR. The phase-cycled bSSFP is a high-SNR sequence which can be used for electrical conductivity mapping [2,3], although its magnitude is known to depend on other biophysical parameters, including diffusion [4] and exchange [5], and on the duration of the RF pulse [6]. These behaviors are each modeled analytically, but no global analytical model exist.In this work, we use EPG-based simulations to investigate how the bSSFP signal magnitude varies with the flip angle, the phase step and the pulse duration in a diffusive, two-pools model of the white matter of the human brain at 3 T. We compare our simulations to in-vivo data, and propose guidelines to optimize the SNR efficiency.

Methods

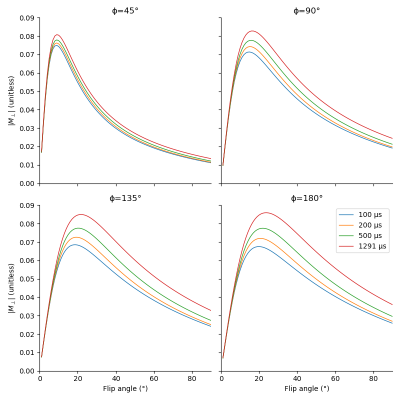

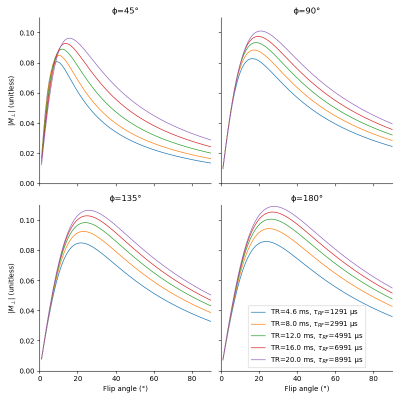

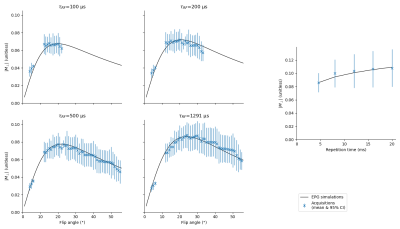

The simulated tissue parameters are based on previous studies [7,8]: T1,a=500 ms, T2,a=18 ms, T1,b=1000 ms, T2,b=13 µs, M0,a=0.8 (magnetization of pool a at equilibrium), ka=3.5 Hz (exchange rate from pool a to pool b), ADC=1700 µm²/ms. Our target resolution is 1.25 mm, with a per-pixel bandwidth of 790 Hz [3]. The maximum gradient amplitude, eventually constraining the maximal duration of the RF pulse, is set to 25 mT/m. EPG simulations are implemented in Sycomore [9], using a 1D discrete model, with pulses discretized at a 5 µs step.The effect of pulse duration is investigated at a fixed TR of 4.6 ms [3], with pulses of 100, 200, 500, and 1291 µs (the longest achievable under the TR, bandwidth, and gradient constraints) and phase steps of 45, 90, 135, and 180°. We then study the effect of the repetition time: a long TR yields a lower SNR, simultaneously allowing a longer pulse improving the SNR. We run simulations with repetition times of 4.6, 8.0, 12.0, 16.0, and 20.0 ms and pulses with maximal duration (respectively 1291, 2991, 4991, 6991, and 8991 µs).

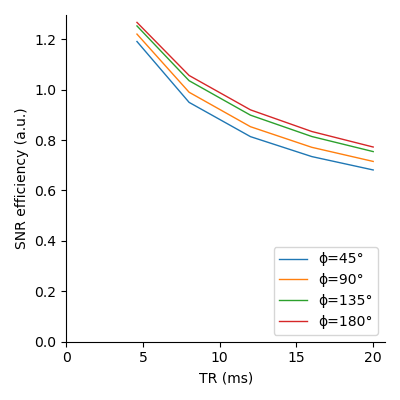

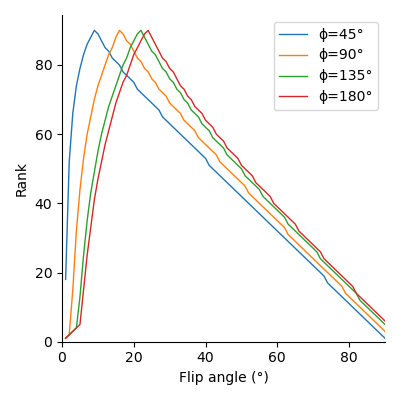

From those simulations, we compute the SNR efficiency, defined as $$$\text{SNR}/\sqrt{\text{TR}}$$$: with a limited acquisition time, a longer TR will reduce the number of trajectories acquired by a factor $$$\eta$$$, causing a related reduction in SNR by a factor $$$\sqrt{\eta}$$$ [10]. We then determine the optimal flip angle with respect to signal magnitude by ranking the magnitudes for each phase step, finding the lowest rank at each flip angle across phase steps, and selecting the flip angle for which the worst signal is maximized.

We validate our simulations on a healthy volunteer using a 3D bSSFP with non-selective pulses, a 12 channels head coil, a field of view of 240 mm, and a phase step of 180°; other sequence parameters are similar to the simulations. With TR=4.6 ms, we use pulse durations of 100, 200, 500, and 1291 µs with flip angles 5°, 15°, 20°, 30°, 40°, and 50°. With repetition times of 4.6, 8.0, 12.0, 16.0, and 20.0 ms, we use the flip angles giving the highest magnitude on simulations (respectively 24°, 25°, 26°, 27°, and 28°). The acquisition protocol also contains an 1 mm isotropic MPRAGE and an B1 map based on the XFL [11] with a 4x4x5 mm resolution. We segment the white matter using Freesurfer and normalize the magnitude of the images to the simulations at a flip angle of 20° for the data at TR=4.6 ms, and, for the data with variable TR, at TR=4.6 ms. We bin the voxels according to their real flip angle with a resolution of 1°, and compare the simulations to the binned data.

Results

Fig. 1 shows that longer pulses will enhance the signal for all phase steps. Moreover, the optimal flip angle depends on the phase step, and, to a lesser extent, on the pulse duration. We can see on fig. 2 that an increase in TR with a corresponding increase in pulse duration will result in an improved SNR for all phase steps. However, since the SNR efficiency is a strictly decreasing function of TR (fig. 3), for a fixed acquisition time, the best efficiency will be given by the lowest TR. The optimal flip angle at TR=4.6 ms (fig. 4) is 18°, where the respective magnitudes for phase steps of 45, 90, 135, and 180° are 0.065, 0.082, 0.083, 0.083, close to the respective maxima of 0.081, 0.083, 0.085, 0.086.The SAR limitations prevented some of the in-vivo acquisitions: flip angles ≥ 30° (respectively ≥ 40°) are missing for the 100 µs pulse (respectively the 200 µs pulse). Fig. 5 shows that simulations and acquisitions agree, validating our analysis.

Discussion and conclusion

Tissue and sequence parameters both affect the bSSFP: while diffusion and exchange reduce the signal magnitude, it can be enhanced by lower TR and increased pulse durations. Although this optimal flip angle differs across phase steps, we have proposed a method giving an optimal overall SNR. Our EPG simulations and analysis are validated by in-vivo acquisitions. Even though a lower TR will improve the SNR efficiency, the existence of a lower bound for this property remains to be investigated.The code and data used in this work are available at https://git.unistra.fr/lamy/pc-bssfp-snr.

Acknowledgements

References

1. Wen. Noninvasive quantitative mapping of conductivity and dielectric distributions using RF wave propagation effects in high-field MRI. In: Medical Imaging 2003: Physics of Medical Imaging. pp. 471–477. SPIE (2003).

2. Gavazzi el al. Transceive phase mapping using the PLANET method and its application for conductivity mapping in the brain. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 83, 590–607 (2020)

3. Iyyakkunnel et al. Configuration-based electrical properties tomography. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 85, 1855–1864 (2021)

4. McNab & Miller. Steady-state diffusion-weighted imaging. NMR in Biomedicine. 23, 781–793 (2010)

5. Bieri & Scheffler. On the origin of apparent low tissue signals in balanced SSFP. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 56, 1067–1074 (2006)

6. Bieri & Scheffler. SSFP signal with finite RF pulses. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 62, 1232–1241 (2009)

7. Pampel et al. Orientation dependence of magnetization transfer parameters in human white matter. NeuroImage. 114, 136–146 (2015)

8. Pierpaoli et al. Diffusion tensor MR imaging of the human brain. Radiology. 201, 637–648 (1996)

9. Lamy & Loureiro de Sousa. Sycomore: An MRI simulation toolkit. In: Proceedings of the 28th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2020)

10. Edelstein et al. The intrinsic signal-to-noise ratio in NMR imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 3, 604–618 (1986)

11. Amadon et al. Validation of a very fast B1-mapping sequence for parallel transmission on a human brain at 7T. In: Proceedings of the 20th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2012)