4594

Impact of a High-Permittivity Helmet on Transmit Efficiency Across a Wide Range of Field Strengths and Relative Permittivities

Giuseppe Carluccio1,2 and Christopher Michael Collins1,2

1Radiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R), New York University, New York, NY, United States

1Radiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R), New York University, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Non-Array RF Coils, Antennas & Waveguides, Non-Array RF Coils, Antennas & Waveguides, High-Permittivity Materials

High-Permittivity Materials are used in MRI to manipulate the B1 field distribution for example to provide a stronger transmit efficiency. For a given coil, the transmit efficiency depends on the frequency. Here we examine the effects of a high-permittivity helmet on the transmit efficiency in exciting the brain with a birdcage coil over a range of frequencies. The optimal frequency providing the maximum transmit efficiency is not significantly impacted by the presence of the helmet, while the maximum efficiency can increase by about 100% compared to when no helmet is used.Introduction

In MRI, a radiofrequency magnetic field, $$$B_1$$$, is used to excite the nuclei in order to generate a detectable signal. The frequency of the $$$B_1$$$ field is directly proportional to the $$$B_0$$$ field of the system. While a stronger $$$B_0$$$ field is associated with higher Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR), the shorter wavelength of the higher-frequency $$$B_1$$$ field poses challenges such as the difficulty in creating a homogeneous excitation in a large volume of interest and higher power absorbed in the tissue for a given $$$B_1$$$ field strength, resulting in greater heating of tissues for a given pulse sequence. The ratio of the transmit field to the square root of the absorbed power is called transmit efficiency (TxEff), and it is a useful parameter in transmit coil evaluation.Use of High-Permittivity Materials (HPM) in MRI to manipulate the $$$B_1^+$$$ field distribution in order to provide a stronger Transmit Efficiency (TxEff), a higher Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR), or even to improve homogeneity in a given volume is becoming increasingly prevalent1,2 . While the most commonly used HPM are flexible pads placed against a portion of the head, there has been increasing interest in the use of helmet-like structures surrounding all or a large portion of the head in MRI at 3T through 10.5T3-5 . The head-sized birdcage coil is commonly used in MRI of the brain at all frequencies up to 7T. It was recently shown that for a specific patient and a specific birdcage coil it is possible to determine the frequency which provides the highest transmit efficiency in the patient’s brain6 . Here we examine the effects of a high-permittivity helmet on transmit efficiency in exciting the brain of a human model with a birdcage coil over a wide range of frequencies.Methods

We evaluated the TxEff through electromagnetic simulations. We used a head-size birdcage coil with 16 legs (28 cm length, 29 cm diameter).The head of the numerical model “Duke” of the Virtual Family7 was positioned at the center of the coil with an HPM helmet around the head (Figure 1). The coil was driven with ideal current sources, the simulations performed with the commercial software xFDTD (Remcom, State College, PA) with 5mm resolution and the RF fields post-processed with MATLAB (The Mathworks; Natick, MA).Simulations were performed at every 10MHz from 50 MHz to 350 MHz with appropriate tissue dielectric properties for each selected frequency, and for HPM helmets with relative permittivity from 50 to 225 with an increment of 25. TxEff was computed as the ratio of the average value of the circular component field in the brain over the square root of the total absorbed power in the entire model.Results and Discussion

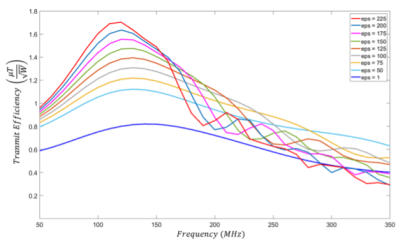

The TxEff as a function of frequency for different helmet permittivity values are plotted in Figure 2. The optimal frequency providing maximum TxEff is not significantly impacted by the presence of the HPM helmet: the optimal frequency is 140 MHz for the case with no helmet (εr=1), and 120 MHz for the highest permittivity considered ( εr= 225). However, it is quite evident from the plots that the use of the HPM helmet has a significant effect on the TxEff curves, especially on the value of maximum TxEff that can be achieved. The maximum TxEff increases by about 100% when εr=225 compared to when no helmet is used ( εr=1). While at low frequencies higher permittivities produce better TxEff, a rapid decline in TxEff with increasing frequency occurs sooner in higher permittivity helmets as well, such that above about 160MHz the helmet providing best TxEff has a progressively lower permittivity.Specifically, for frequencies higher than 160 MHz we could find that the permittivity values providing the highest TxEff can be approximated with the relationship $$$\epsilon_{r,opt}=\frac{4106MHz^2}{(f-20MHz)^2} $$$ , which is in strong agreement with the findings in a previous publication8 .Nonetheless, at every frequency use of an HPM helmet has the potential to increase transmit efficiency, even as the optimal permittivity of the helmet approaches the average permittivity of tissues at 300 MHz. It is also notable that the optimal permittivity found here for TxEff of the head-sized birdcage coil for whole brain is lower than permittivities used at 7T for other purposes, such as enhancing $$$B_1$$$ specifically in the temporal lobes1,2 or increasing receive SNR of a close-fitting array4 , but the defined goal here is also different than prior goals. As the head-sized birdcage coil is used currently at all major field strengths for human imaging, the potential to improve its efficiency can be seen as very important, but the effect on receive arrays is also a major consideration not addressed here.Acknowledgements

This work was performed under the rubric of the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R, www.cai2r.net) at the New York University School of Medicine, which is an NIBIB Biomedical Technology Resource Center (NIH P41 EB017183) with additional funding from NIH R01 EB021277.References

- Webb, Conc. Magn Reson A, 2011 Jul;38(4):148-84.

- O’Brien et al., J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014 Oct;40(4):804-12.

- Sica et al., Magn Reson Med. 2020 Mar;83(3):1123-34.

- Lakshmanan et al., Magn Reson Med. 2021 Aug;86(2):1167-1174

- Gandji et al., Magn Reson Med, 2021 86:3292–3303

- Carluccio and Collins, Proc. 2021 ICEAA, p. 365

- Christ et al., Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:N23- N38

- Collins et al., Proc. 2019 ISMRM, p. 1566

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4594