4555

The MR-Bioreactor : Micro-MRI of thick living tissues to characterize 4-days old ex-ovo chick embryo morphology.1Université de Lyon, INSA Lyon, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Ecole Centrale de Lyon, CNRS, Ampère UMR5005, Villeurbanne, France, Lyon, France, 2MeLis, CNRS UMR 5284-INSERM U1314-Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1 Institut NeuroMyoGène, Lyon, France, Lyon, France

Synopsis

Keywords: New Devices, Animals

Thanks to their accessibility for experimental manipulations, their availability and their low cost, chick embryos have been used as animal models for developmental biology for long. In these applications, non-invasive 3D imaging of the embryos is needed to monitor the embryos development. Morphological characterization of ex-ovo chick embryo generally require tissue fixing which can alter MR characterizations. In this work, we use our MR-Bioreactor to perform a high resolution morphological characterization of a chick embryo maintained in living conditions.Introduction

Chick embryos have been used as animal models for developmental biology for long. This model holds several advantages. For example, the embryo is easily accessible for experimental manipulations including grafting and gene gain- and loss-of-function by electroporation1. Chick embryo were used to study different aspects of the development from axis specification to organogenesis and notably neurodevelopment, but this model is also used to study tumor progression2. In these applications, non-invasive 3D characterizations of the embryos are needed for development monitoring. While optical modalities can be used, they often require additionnal experimental manipulation depending on the optical technique used. Moreover the tradeoff between the necessary high resolution, an important depth of penetration and a large field of view often lead to multiple acquisitions depending on the embryo development stage. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) offers non-invasive, multiparametric and multiscale 3D characterizations with large field-of-view. While ideal for longitudinal probing of chick embryo development3,4 in ovo MRI suffers from several limitations. Image artifacts can arise from the air contained in eggs or from chick embryo movements which can be limited by a cooling of the egg or direct embryo anesthesia. In addition, throughout its development the embryo’s location within the egg is changing, which leads to a change in achievable SNR within the embryo. Furthermore, commercial volume coils, in which eggs can fit, which are not optimized i.e with poor filling factors are generally used for these characterizations. The combination of these two factors generally lead to chick embryo characterizations to either use ultra high-fields (<9.4T)5,6, long acquisition times (<3h)7, or contrast agent8 to reach resolutions below 100 microns which are needed especially for early stage development chick embryos. On the other hand for punctual probing, ex-ovo characterizations allow for more optimization in the MR setup. However, these characterizations usually require tissue fixing7 to avoid tissue degradation before or during the MR experiment which can be detrimental to morphological assessment of the chick embryo development9. To tackle this, we use an improved version of our MR-bioreactor10 to perform a morphological characterization of an ex-ovo chick embryo embedded in agarose and maintained in living conditions.Method

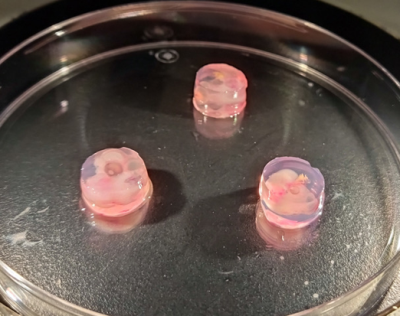

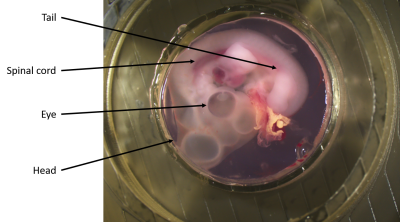

Fertilized eggs were incubated, for four days, at 38.5°C in a humidified incubator. On the day of the experiments, the egg shell was opened and the embryos were collected. The embryos were transferred into a 4°C F12 culture medium and the extraembryonic membranes were removed. Embryos were embedded in 1% agarose gel. The Agarose/F12 mixture was heated in a microwave to melt the agarose and let to equilibrate 40°C in a water bath before use. Then a small amount of Agarose/F12 mixture was used to cover the bottom of a 3D printed custom-made ring container. On top of this, an embryo is placed and the custom-made ring container is filled with the rest of Agarose/F12 mixture. The whole sample was then left to gel at room temperature (figure 1). The embedded embryo was put inside the MR-Bioreactor (figure 2) which was connected to a peristaltic pump. The pump was pumping F12 from a reservoir at a 1.75mL/min flow rate for 10min. The pump was then turned off during imaging to avoid flow artifacts. The tubes were not emptied and remained full of F12 to ensure tissue viability during the acquisition time. A 7T Bruker MRI Scanner using Paravision 5.1 was used for the acquisitions. A 72mm diameter birdcage was used for transmission while the 12mm loop surface coil of the MR-Bioreactor was used for reception (figure 3).Three sequences were used :

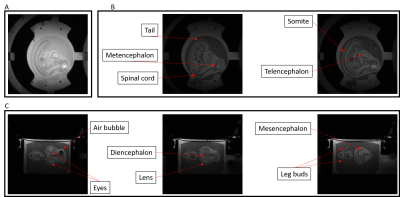

- Morphological :Coronal Turborare T2 (TE=17.5ms, TR=4883.1ms, FOV 20mm*20mm, 78microns*78microns*500microns, 16 averages, Acquisition time 31min 15s.)

- Morphological : Axial Turborare T2 (TE=17.5ms, TR=6185.26ms, FOV 20mm*20mm, 78microns*78microns*500microns, 16 averages, Acquisition time 39min 35s.)

- T2 Mapping : Coronal MSME T2 (∆TE= 11ms, 16 echos, TR=4816ms, FOV 20mm*20mm, 150microns*150 microns*500microns, Acquisition time 30min 49s.)

Prior to these acquisitions, a cell viability test was run to check if the MR-Bioreactor was able to maintain the sample in living conditions for 1h30 of F12 in continuous F12 flow outside of the MR Scanner. The spinal cord of an agarose embedded embryo was extracted and its cells were marked with Trypan blue. The results were then compared to a control embryo of which the spinal cord was extracted just before the test.

Results

Figure 4 illustrate the morphological characterization at 78mm² in plane resolution of a chick embryo. Various morphological features of a 4 days-old chick embryo development can be extracted from these acquisitions and compared with reference anatomical atlas.The test performed on dissociated neurons shows a cell viability of 97.93% after incubation in the MR-Biorector which is close from the viability measured on freshly collected embryo (99,01%).

Conclusion

In this work, we demonstrate the ability of our MR-Bioreactor to characterize at high-resolution important features that are stage-dependent in the development of chick embryo. The MR-Bioreactor was shown to have no impact on the cell viability. These results coupled with the compatibility of the MR-Bioreactor with optical techniques could pave the way for 3D Multimodal characterizations of animal models with thick living tissues.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Agence National de la Recherche (Estimate Project N° ANR-18-CE19-0009-01). Moreover, the role of CERMEP - Imagerie du vivant and especially Radu Bolbos is also acknowledged. Finally, the role of Stephane Martinez and his team from Atelier Mecanique Université Lyon 1 is aknowledged.References

(1) Sauka‐Spengler, T.; Barembaum, M. Chapter 12 Gain‐ and Loss‐of‐Function Approaches in the Chick Embryo. In Methods in Cell Biology; Elsevier, 2008; Vol. 87, pp 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-679X(08)00212-4.

(2) Herrmann, A.; Taylor, A.; Murray, P.; Poptani, H.; Sée, V. Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Characterization of a Chick Embryo Model of Cancer Cell Metastases. Mol Imaging 2018, 17, 153601211880958. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536012118809585.

(3) Duce, S.; Morrison, F.; Welten, M.; Baggott, G.; Tickle, C. Micro-Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of Live Quail Embryos during Embryonic Development. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2011, 29 (1), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2010.08.004.

(4) Zhou, Z.; Chen, Z.; Shan, J.; Ma, W.; Li, L.; Zu, J.; Xu, J. Monitoring Brain Development of Chick Embryos in Vivo Using 3.0 T MRI: Subdivision Volume Change and Preliminary Structural Quantification Using DTI. BMC Dev Biol 2015, 15 (1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12861-015-0077-6.

(5) Zuo, Z.; Syrovets, T.; Genze, F.; Abaei, A.; Ma, G.; Simmet, T.; Rasche, V. High-Resolution MRI Analysis of Breast Cancer Xenograft on the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane: IN OVO HIGH-RESOLUTION MRI OF BREAST CANCER XENOGRAFT. NMR Biomed. 2015, 28 (4), 440–447. https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.3270.

(6) Hogers, B.; van der Weerd, L.; Olofsen, H.; van der Graaf, L. M.; DeRuiter, M. C.; Groot, A. C. G.; Poelmann, R. E. Non-Invasive Tracking of Avian Development in Vivo by MRI. NMR Biomed. 2009, 22 (4), 365–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.1346.

(7) Li, X.; Liu, J.; Davey, M.; Duce, S.; Jaberi, N.; Liu, G.; Davidson, G.; Tenent, S.; Mahood, R.; Brown, P.; Cunningham, C.; Bain, A.; Beattie, K.; McDonald, L.; Schmidt, K.; Towers, M.; Tickle, C.; Chudek, S. Micro-Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Avian Embryos. Journal of Anatomy 2007, 211 (6), 798–809. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00825.x.

(8) Smith, B. R.; Effmann, E. L.; Allan Johnson, G. MR Microscopy of Chick Embryo Vasculature. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 1992, 2 (2), 237–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.1880020220.

(9) Shepherd, T. M.; Thelwall, P. E.; Stanisz, G. J.; Blackband, S. J. Aldehyde Fixative Solutions Alter the Water Relaxation and Diffusion Properties of Nervous Tissue: Aldehyde Fixation Alters Tissue MRI Properties. Magn. Reson. Med. 2009, 62 (1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.21977.

(10) Gnanago, J.-L.; Gerges, T.; Chastagnier, L.; Petiot, E.; Semet, V.; Lombard, P.; Marquette, C. A.; Cabrera, M.; Lambert, S. A. 3D MRI Characterization of 3D Printed Tumor Tissue Models Using a Plastronic MR-Bioreactor : Preliminary Results. Proceedings of the 30th International Society in Magnetic Resonance for Medecine Annual Meeting 2003 (2022) 2022, 3.

Figures