4551

Self-contained Small Animal Imaging Insert for Clinical MRI Systems1Ulm University Hospital, Ulm, Germany, 2Core Facility Small Animal Imaging (CF-SANI), University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: New Devices, Preclinical

For measuring small objects or animals in a clinical MRI system specialised vendor-specific coils can be applied to overcome SNR limitations. Instead, we suggest using resonant inductive coupled vendor unspecific receive coils, for enhancing the SNR in a small local ROI, of e.g. the systems inbuilt body coil by a factor of up to 34. For simple usage, autotuning capabilities were integrated to automatically compensate for different loads, thus enabling imaging of small objects or animals without any modification to the work-flow, preparation and scanning process on a clinical MRI system.

Introduction

Small animal imaging is frequently applied in preclinical research. To fulfil the high demands regarding spatial resolution for most studies dedicated high- or ultra-high field small animal systems are used, which cause high installation and operational costs as well as the need for specifically trained personnel. Further high field-strengths often do not allow direct transfer of preclinical results to the clinical situation due to different relaxation and relativity properties. However, in many cases, the field strength and gradient power of conventional clinical systems are sufficient for providing sufficient image fidelity at reasonable spatial resolution in case optimized RF chains are applied 1, which are not readily available by the vendors, rather expensive and often not optimized for efficient use in the context of small animal imaging.We suggest to use a simple passive resonant coil (solenoid, saddle coil), which is inductively coupled to the inbuilt QBC of the clinical system. The coil is part of a self-contained insert providing animal handling (fixation, anaesthesia, monitoring, heating). To compensate for different loads of the coil, an autotune capability has been integrated, thus yielding an easy-to-use and vendor independent small animal insert, which can be completely set-up outside of the scanner room and directly used with the available, well-established imaging sequences on the clinical MR system.

Method

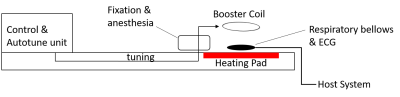

The SNR efficiency of RF coils is strongly depending on the filling factor $$$n_{f}=\frac{B_{1}^2}{Q\times P}$$$, with the Q-ratio of the coil (Q), the input power (P) and the resulting RF field (B1) 2. Thus $$$n_{f}$$$ can be maximised by placing the RF coil near to the sample and by increasing the Q-ratio of the resonator, which is normally done by using dedicated receive coils fitted to the ROI and connected to the MRI system. As reported earlier3, local resonant structures at the same frequency can be used for increasing the SNR of a common volume resonator in MR Imaging, and for e.g. adding a resonator array inside of a 7.4T Head Coil was shown to yield significant improvement in B1 uniformity and SNR in the cerebellum and brainstem4 as-well as increased the visible region of the coil.We have designed simple solenoid and saddle-coils, which are inductively coupled to the QBC. Since the B1 field of the QBC is sufficiently homogenous for the small ROI, the coils have only been used for signal reception and passively decoupled with crossed-diodes (BAV99) during spin excitation. As such, the amplification of the local signal only occurs during signal reception and the scanner can perform all required preparation steps, here especially power optimisation and SAR estimation, as usual, but under full consideration of the signal boost by the local coils. Autotuning of the local booster coils has been realized by integration of a varactor diode (SMV1234-079LF) and a microcontroller (STM32F413ZHT6) which enabled analysis and adjustment based on the S11 curve. Active heating of the animal was realized by adding a resistive heating pad, the design of which was optimized to minimise current-induced magnetic field distortions. Physiology signals (ECG, respiratory bellows) were directly interfaced to the scanner (Fig.1).

Results

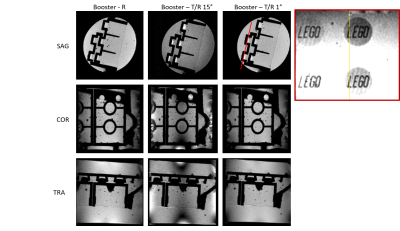

The autotune resulted in accurate tuning of the coil, independent on its load. In comparison to the QBC the tuned booster coils yielded a reproducible increase of SNR of up to a factor of 34 (Fig. 2). The gain in SNR could be used to acquire high-resolution isotropic 3D images as exemplary shown for a Lego brick (Fig.3) and an excised mouse brain (Fig.4) on an unmodified clinical scanner. Acquisition parameters are provided in tab.1.Conclusion

With the suggested self-contained small animal insert, high-resolution small animal imaging is feasible with a rather simple vendor-independent approach. Since the booster coil is not interfaced to the scanner hardware, operation for animals and samples should not rise any legal or ethical concerns.Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 858149. The authors thank the Ulm University Centre for Translational Imaging MoMAN for its support.References

1. Herrmann K-H, et al. Possibilities and limitations for high resolution small animal MRI on a clinical whole-body 3T scanner. Magma (New York, N.Y.) 2012;25:233-244

2. Gruber B, et al. RF coils: A practical guide for nonphysicists. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2018;48:590-604

3. Shan D, et al. Wireless power transfer system with enhanced efficiency by using frequency reconfigurable metamaterial. Sci Rep. 2022;12:331

4. Alipour A, et al. Improvement of magnetic resonance imaging using a wireless radiofrequency resonator array. Scientific

reports. 2021;11:23034

Figures

Figure 1: Schematic of the designed insert with autotuned booster coils, resistive heating, fixation and anesthesia for the mice and pass through of the patient monitoring to the host system.

Figure 2: SNR comparison: (a) only QBC: SNR=5.81, (b) with Booster: SNR=199.81, (c) changed load without retuning: SNR=122.68, (d) tuned for new load as in (c): SNR=198.96.

Figure 3: High isotropic spatial resolution of a Lego brick embedded in agarose. Red line indicates the location of the reformat of the 3D volume.

Figure 4: High-resolution (left) and medium resolution (right) image of an excised mouse brain.

Table 1: Scanning parameters.