4523

Volumetric vocal tract segmentation using a deep transfer learning 3D U-Net model1Roy J Carver Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Iowa, iowa city, IA, United States, 2Janette Ogg Voice Research Center, Shenandoah University, Winchester, IA, United States, 3Department of Radiology, University of Iowa, iowa city, IA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Head & Neck/ENT

The investigation into the 3D airway area is the prerequisite step for quantitatively studying the anatomical structures and function of the upper airway. Segmentation of upper airway can be considered as one of the stepping stones for this investigation. In this work, we propose a transfer learning-based 3D U-Net model with a ResNet encoder for vocal tract segmentation with small datasets training. We demonstrate its utility on sustained volumetric vocal tract MR scans from the recently released French speaker database.Purpose

The human vocal tract is an exquisite instrument capable of producing fluent speech. Recently, accelerated volumetric vocal tract MRI schemes have demonstrated fast imaging of the entire vocal tract during sustained production of speech tokens (eg. sustained utterances of English and French phonemes in <10 seconds) [1]. Quantitatively assessing vocal tract posture modulation (e.g. via vocal tract area functions) has advanced our linguistic understanding of speaker-to-speaker variability and the underlying phonetics of language and song [2]. These approaches are labor and time intensive. Recently, deep learning-based U-Net models have been applied to segment the upper airway in static 3D upper-airway MRI volumes [3]. However, these require large amounts of annotated training samples (of the order of 206 volumes). There is thus a need for an efficient volumetric segmentation algorithm that can be trained with a small annotated dataset and yet produce accurate results. In this work, we propose a transfer learning-based 3D U-Net model with a ResNet encoder for vocal tract segmentation with small dataset training. We demonstrate its utility on sustained volumetric vocal tract MR scans from the recently released French speaker database [1].Methods

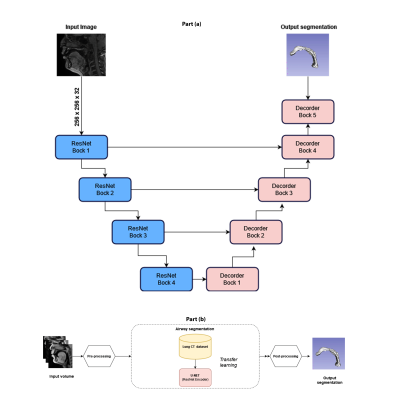

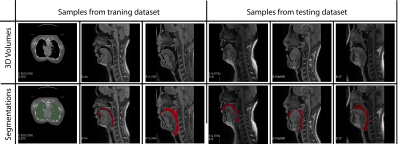

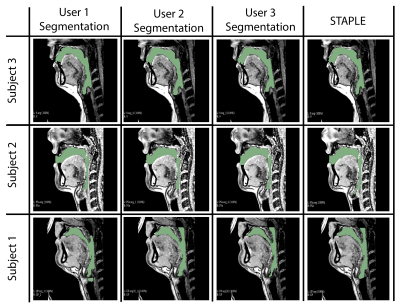

Our model learns the mapping between input static 3D MRI volume and the volumetric vocal tract segmentation. Figure 1 (a) shows the 3D U-Net architecture. The model employs a ResNet-18 [4] encoder and U-Net [5] decoder. The model is trained by minimizing the Dice similarity between the predicted segmentation and the corresponding ground truth segmentation in the training set. For transfer learning, the network was initially trained with an open-source AAPM 2017 Thoracic Auto-segmentation Challenge dataset [6]. This dataset contained multi-organ segmentation and we have only considered the lung segmentations. The rationale behind using lung segmentations as a transfer learning dataset is to apply auxiliary training for upper airway segmentation. We have considered 25 lung computed tomography (CT) volumes for pre-training the network. Subsequently, the first 5 layers were frozen and the rest of the layers were fine-tuned with the French speaker vocal tract MRI datasets. An illustration of the training pipeline is provided in Figure 1 (b). The proposed training pipeline allows low-level features to be learned from the CT dataset, while medium- and high-level features can be learned from the French speaker dataset [1] consisted of 10 speakers with over 750 postures. In this work, randomly selected 26 postures from all 10 speakers are used. The number of datasets in the training, testing, and validation sets respectively were 17, 1, and 8. Samples from the French speaker dataset are provided in Figure 2.Pre-processing was performed on both the CT and MRI datasets. Their initial pixel intensities were scaled to a range of -1 to 1. For the upper airway, the airway anatomy was cropped to the area of interest which starts from the lips and ends near the glottis region. The network architecture was developed using Keras and TensorFlow [7] on an NVIDIA A30 GPU. The training was conducted for 500 epochs which took approximately 1.5 hours. The output segmentation was post-processed using the Slicer software to remove any non-anatomical segmentations manually using the eraser tool on the pharyngeal or infra glottis region. The performance of the network was evaluated using the Dice coefficient. Instead of using a single manual segmentation as ground truth, we used the STAPLE [8] method to generate an optimum segmentation using manual segmentations from 3 different observers (2 graduate students with expertise in image processing, upper-airway anatomy, and 1 vocologist). This method allows us to create new reference segmentation with less interobserver variability. An example of three different manual segmentations and their corresponding STAPLE segmentation is given in Figure 3.

Results

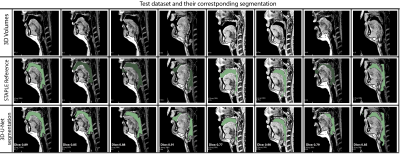

Figure 4 shows the Dice coefficient comparison for 8 test volumes from 3 different subjects. It can be observed that 75 percent of the segmentations have shown dice scores above 0.8. Once trained, the network took an average processing time of 10 seconds per volume and 4 minutes for post-processing using Slicer. To appreciate the quality of segmentation we have provided a GIF animation of the volumetric segmentations for 2 subjects in the test dataset along with corresponding reference segmentations (Figure 5). We note the quality of the 3D U-Net segmentations to be accurate near the roof of the tongue, the base of the velum, and around the epiglottis. However, it had some notably missed segmentations in thin airway openings behind the oropharynx (Figure 4 column 5) and openings between the lips (Figure 4 column 7). Further investigations in refining the network model to address these limitations are needed and will form the scope of our future workConclusion

We have demonstrated vocal tract segmentation from a 3D static upper airway MRI with small dataset training (17 volumes). The network is trained to learn the mapping between upper airway MRI volume and airway segmentation by leveraging information from open-source CT datasets. Once trained, the model can perform airway segmentation on the order of 4 minutes and 10 seconds including post-processing time on NVIDIA A30 GPU. We also demonstrate that transfer learning has the potential to be an efficient tool for small dataset training for upper airway segmentation.Acknowledgements

This work was conducted on an MRI instrument funded by 1S10OD025025-01References

[1] K. Isaieva, Y. Laprie, J. Leclère, I. K. Douros, J. Felblinger, and P.-A. Vuissoz, “Multimodal dataset of real-time 2D and static 3D MRI of healthy French speakers.,” Sci Data, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 258, 2021, doi: 10.1038/s41597-021-01041-3.

[2] K. Tom, I. R. Titze, E. A. Hoffman, and B. H. Story, “<title>Volumetric EBCT imaging of the vocal tract applied to male falsetto singing</title>,” in Medical Imaging 1996: Physiology and Function from Multidimensional Images, Apr. 1996, vol. 2709, pp. 132–142. doi: 10.1117/12.237856.

[3] V. L. Bommineni et al., “Automatic Segmentation and Quantification of Upper Airway Anatomic Risk Factors for Obstructive Sleep Apnea on Unprocessed Magnetic Resonance Images,” Acad Radiol, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2022.04.023.

[4] K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun, “Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition,” Dec. 2015, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1512.03385

[5] Ö. Çiçek, A. Abdulkadir, S. S. Lienkamp, T. Brox, and O. Ronneberger, “3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation,” Jun. 2016, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1606.06650

[6] J. Yang et al., “Autosegmentation for thoracic radiation treatment planning: A grand challenge at AAPM 2017,” Med Phys, vol. 45, no. 10, pp. 4568–4581, Oct. 2018, doi: 10.1002/mp.13141.

[7] M. Abadi et al., “TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Distributed Systems,” Mar. 2016, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1603.04467

[8] S. K. Warfield, K. H. Zou, and W. M. Wells, “Simultaneous Truth and Performance Level Estimation (STAPLE): An Algorithm for the Validation of Image Segmentation,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 23, no. 7, pp. 903–921, Jul. 2004, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2004.828354.

Figures