4521

Finite element simulation of breast hyperelasticity to develop a non-rigid registration model by deep learning1Research and Innovation Department, Olea Medical, La Ciotat, France

Synopsis

Keywords: Breast, Data Processing, Registration, Motion correction

This work is part of an ongoing study to correct accidental breast motion during dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging. Here, we explored a finite element method to generate “moving” images based on a “fixed” one. The proposed methodology can help in the constitution of realistic dataset with large variety of motion to support the development of a dedicated non-rigid registration model by deep learning.Introduction and Context

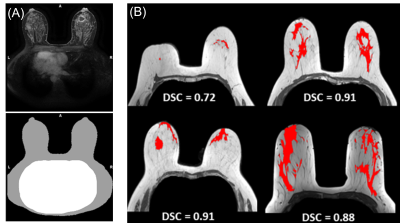

Image registration is an active field of research that focuses as much on fusion between different imaging modalities as on motion correction between sequences phases in MRI, and as well on patient follow-up. Registration process enables to merge spatially correlated anatomical information into a single coordinate system. In this way, local biomarkers can be estimated or/and compared among imaging techniques.This preliminary work is part of an ongoing study to correct accidental breast motion during dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging (DCE-MRI). The recovery of spatial coherence between DCE-MRI phases is crucial to estimate kinetics biomarkers. Indeed, the duration of breast MRI exam is about 20 to 30 minutes depending on the sequences used (e.g., T1w, T2w, DWI, DCE). The DCE sequence ends the exam with a duration of about 5 to 8 minutes depending on the number of phases, and on the temporal step between each phase. Such duration may induce postural discomfort and the breast volume in each DCE-MRI phase is prone to motion, as illustrated in Fig.1.

Recent medical image registration studies reported the benefits of deep learning strategies [1]–[3]. Deep learning registration methods offer lower computation time and sufficient accuracy. Indeed, traditional image registration methods [4], [5] are iterative-based procedures and can have incompatible computation time with clinical practice. This is particularly true for breast images when looking for non-rigid transformations on a large field of view.

The counterpart of supervised deep learning methods is the large amount of data required to achieve a robust model. In other words, numerous pairs of “fixed” and “moving” images must be available for the training. This abstract explores a finite element method (FEM) to generate several “moving” images based on a “fixed” one, based on a realistic elastic deformation of soft tissues to create a relevant dataset to train a non-rigid registration model.

Methods

Mechanical simulationThe simulation of the deformation field must be as realistic as possible to obtain a registration model suitable for clinical application. The development of a mechanical simulation was a straightforward choice. Female breasts contain different types of soft tissues and makes it a particularly deformable medium. Fat tissue, fibroglandular tissue and skin are considered to be quasi-incompressible isotropic hyperelastic material, as described in [6]. The Neo-Hookean hyperelastic modelisation [7] has been implemented with the FEniCS toolkit [8].

Calculation domains

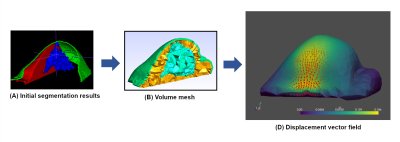

The different mechanical behavior of the breast components implies knowledge of their spatial extent in order to take this into account in modelling. Thus, three main components were extracted from the DCE-MRI phase: fatty tissues, fibroglandular tissues and the skin. Cooper's ligaments have been excluded because they are not visible on the T1w image, even though their role in maintaining fibroglandular tissues is indisputable. Fibroglandular tissue extent was obtained using a homemade deep learning segmentation model [9]. Overall Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) reached a median value of 0.917, providing an appropriated confidence to estimate the fibroglandular domain, as illustrated in Fig.2B. Breast domain was also obtained using a homemade deep learning model dedicated to breast and thorax segmentation (Fig.2A). The median DSCs obtained with this model are 0.973 for the breast, and 0.963 for the thorax, providing a high level of confidence. The fatty tissue domain was defined by subtracting the breast domain from the fibroglandular domain. The skin domain was obtained by an erosion process of the breast segmentation area. The skin thickness was taken to be 1.55 millimeters for the whole breast, as reported on average in [10].

Breast motions

Patients are installed in MR system in prone position with the breasts subjected to gravity. After numerous case reviews, we assume the sternum and rib cage remain motionless in contact with the examination table. Most of the observed motions (Fig.1) are related to the mobilization of the shoulder joint. This leads to stretching or loosening of the skin in the axilla and upper pectoral areas, causing an overall displacement of the breast tissue. Different skin surface conformations to apply the force are still being evaluated.

Results

According to the described method, the three breast components were obtained with deep learning models, as shown in Fig.3A. These three domains are then meshed with a tetrahedral geometry (Fig.3B).A loosening of the skin was modelled to illustrate a typical breast motion observable in DCE-MRI. A force was defined with an orientation starting from the axilla to the nipple. The force surface application was a rectangular tape-like shape placed in the axillary region and following the shape of the breast. The tangential component of the force was projected onto the defined skin surface. The finite element modelisation resulted in a local estimation of the motion vector (i.e., displacement field) inside the breast bulk (Fig.3C). The generation of the “moving” image was done by applying of the resulting displacement field on the “fixed” image.

Discussion and Conclusion

Presented results are still preliminary, and some points need to be addressed. Particularly, some anatomical parts are missing such as the pectoral muscle or the rib cage. However, the proposed methodology can help in the constitution of realistic dataset with large variety of motion to support the development of a dedicated non-rigid registration model by deep learning.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] S. Bharati, M. Rubaiyat, H. Mondal, P. Podder, and V. B. S. Prasath, “Deep Learning for Medical Image Registration: A Comprehensive Review,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2204:11341, 2022.

[2] G. Balakrishnan, A. Zhao, M. R. Sabuncu, J. Guttag, and A. v. Dalca, “VoxelMorph: A Learning Framework for Deformable Medical Image Registration,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 38, no. 8, pp. 1788–1800, 2019.

[3] Y. Fu, Y. Lei, T. Wang, W. J. Curran, T. Liu, and X. Yang, “Deep learning in medical image registration: a review,” Phys Med Biol, vol. 65, no. 20, p. 20TR01, Oct. 2020.

[4] F. P. M. Oliveira and J. M. R. S. Tavares, “Medical image registration: A review,” Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 73–93, 2014.

[5] K. Marstal, F. Berendsen, M. Staring, and S. Klein, “SimpleElastix: A User-Friendly, Multi-lingual Library for Medical Image Registration,” IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, pp. 574–582, Dec. 2016.

[6] G. Dufaye, A. Cherouat, J. M. Bachmann, and H. Borouchaki, “Advanced finite element modelling for the prediction of 3D breast deformation,” in European Journal of Computational Mechanics, vol. 22, no. 2–4, pp. 170–182, Aug. 2013

[7] P. A. L. S. Martins, R. M. Natal Jorge, and A. J. M. Ferreira, “A Comparative Study of Several Material Models for Prediction of Hyperelastic Properties: Application to Silicone-Rubber and Soft Tissues,” Strain, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 135–147, Aug. 2006.

[8] M. S. Alnaes et al., “The FEniCS Project Version 1.5,” Archive of Numerical Software, vol. 3, no. 100, pp. 9–23, 2015.

[9] F. Ouadahi, A. Bernard, L. Brun, and J. Rouyer, “Automatic fibroglandular tissue segmentation in breast MRI using a deep learning approach,” in in Proc. of International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2022.

[10] A. Sutradhar and M. J. Miller, “In vivo measurement of breast skin elasticity and breast skin thickness,” Skin Research and Technology, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. e191–e199, Feb. 2013.

Figures