4510

Enhanced 129Xe T1 relaxation in blood and in presence of SPIONs at low field strengths1Physics and Astronomy, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Hyperpolarized MR (Non-Gas), Relaxometry

We demonstrate enhanced T1 relaxation of hyperpolarized 129Xe spins in blood and in the presence of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) at low field strengths.Introduction

Most applications of hyperpolarized 129Xe gas at high field can be grouped in two main categories, depending on whether the gas phase or the dissolved phase is detected. In vivo gas-phase imaging applications generally include lung ventilation imaging and molecular lung imaging, where the gas is used in combination with iron oxide nanoparticles that yield enhanced sensitivity and molecular specificity to the detection1,2. In vivo dissolved-phase imaging applications at high field, enabled by the relatively long relaxation time of xenon in blood and the recent improvements in gas polarization efficiency, range from the detection of gas exchange in the lungs, to brain perfusion, kidney perfusion, and temperature imaging3-5.At low magnetic field strengths, hyperpolarized gases have been used only for lung ventilation studies, despite the wide difference in chemical shift between the dissolved phase and gas phase resonances, which could in principle enable both gas phase and dissolved-phase imaging6-8. Here, by performing a set of in vivo and in vitro measurements, we assess the feasibility of extending some of the hyperpolarized 129Xe gas applications from high field to low field. In particular, by performing relaxation studies at high and low field strengths, we assess the sensitivity of hyperpolarized gases to SPIONs that have been used at high field for molecular imaging in the lungs, and more recently have been shown to predominately affect the longitudinal relaxation of nearby spins at low field9-11. Then, to assess the feasibility of dissolved-phase 129Xe MRI at low field, we perform in vivo experiments at variable field strengths to determine the relaxation properties of xenon in blood.

Methods

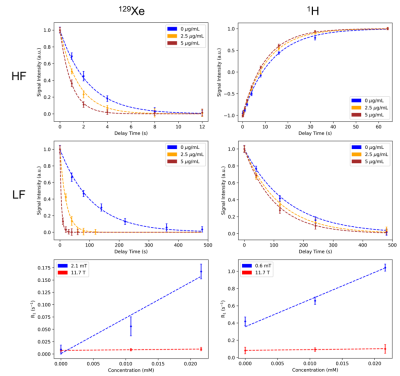

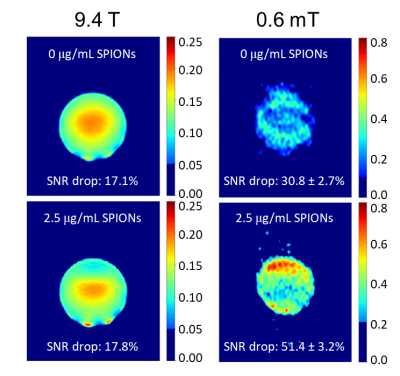

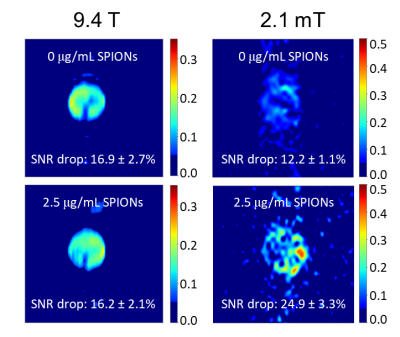

SPION-induced 1H and 129Xe relaxivities were measured on samples of deionized water containing SPIONs at different concentrations, using a Varian NMR spectrometer operating at 11.7T, as well as a home-made MRI system operating at 2.1mT12. 1H measurements at high field were performed by using an inversion recovery sequence, while a variable delay was placed between gas delivery and excitation to measure the relaxation of dissolved 129Xe13. For 1H measurements performed at 0.6mT, the sample was first placed in a 0.4T permanent magnet to polarize the 1H spins, and then rapidly transported to 2.1mT, where a variable delay was placed before excitation and detection to allow for T1 relaxation to occur. For 129Xe at 2.1mT, the protocol used at high field was followed exactly.Imaging of SPION samples was also performed by using the low field MRI system and a 9.4T Bruker Biospect MRI system. For imaging, a modified gradient echo sequence was used with additional delay times to allow for varied durations of longitudinal relaxation to occur. Basic image subtraction was used to calculate the contrast obtained as a result of the increased delay time.

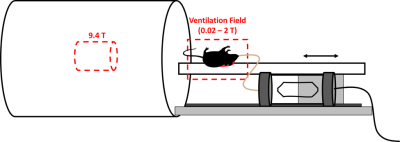

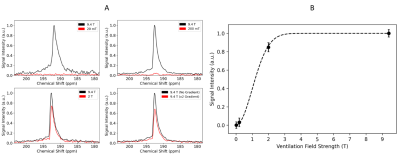

129Xe depolarization studies in blood were performed by using the same 9.4T MR system used to image the SPION samples. For these experiments, the mouse was placed on a rail system concentric with the bore of the magnet. A surface coil was placed on the back of the mouse such that a relatively large dissolved-phase signal could be detected from xenon dissolved in the interscapular brown fat of the animal (Fig. 1). Before each acquisition, the mouse was ventilated with hyperpolarized xenon gas for one minute, while sitting in the fringe field of the 9.4T magnet, at field strengths ranging from 0.02 - 2T, before the signal was detected at 9.4T. Control experiments were performed to account for 129Xe depolarization during the transport of the animal in and out of the magnet.

Results

At low field, both 1H and 129Xe spins experienced a much larger increase in their respective longitudinal relaxation rates as a result of their interactions with the unsaturated magnetization of SPIONs (Fig. 2). More specifically, the SPION relaxivity increased from 0.92 ± 0.06 to 31.5 ± 1.8 mM s-1 for 1H and from 0.13 ± 0.03 to 7.32 ± 0.71 mM s-1 for 129Xe. This enhanced T1 relaxivity led to increased MRI contrast consistent with the spectroscopic results. While at high field (left column of Fig. 3 and 4) SPIONs do not generate detectable contrast at the low concentration used here (top and bottom images appear almost identical), at low field (right column) significant T1 contrast is achieved.Total signal loss is reported for in vivo dissolved 129Xe when the animal was ventilated at fields lower than 200mT, suggesting depolarization of xenon in blood on a time scale of milliseconds (Fig. 5).

These results, together with additional results obtained at low field using mixtures of water and blood, suggest an increased depolarization effect of the paramagnetic deoxyhemoglobin molecules found in blood at low field compared to high field14,15.

Conclusions

As with 1H, dissolved 129Xe experiences accelerated longitudinal relaxation in the presence of SPIONs at low field strengths. As a result, SPIONs serve as effective T1 contrast agents in this regime for both 1H and dissolved 129Xe MRI and could be used for molecular imaging applications of combined hyperpolarized xenon gas and SPIONs in the lungs at low field. The enhanced depolarization of xenon in blood observed at low field effectively prevents the extension of dissolved-phase imaging and spectroscopy applications in this regime.Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the NIH grants R01DK108231, R01DK123206, and R21EB031319; and the NSFGraduate Research FellowshipDGE-1650116.References

1. Branca, R. T. et al. Molecular MRI for sensitive and specific detection of lung metastases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 3693–3697 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.1000386107

2. Vignaud, A. et al. Magnetic susceptibility matching at the air-tissue interface in rat lung by using a superparamagnetic intravascular contrast agent: Influence on transverse relaxation time of hyperpolarized helium-3. Magn. Reson. Med. 54, 28–33 (2005). 10.1002/mrm.20576

3. Branca, R. T. et al. Detection of brown adipose tissue and thermogenic activity in mice by hyperpolarized xenon MRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 18001–18006 (2014). 10.1073/pnas.1403697111

4. Myc, L. et al. Characterisation of gas exchange in COPD with dissolved-phase hyperpolarised xenon-129 MRI. Thorax 76, 178–181 (2021). 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-214924

5. Chacon-Caldera, J. et al. Dissolved hyperpolarized xenon-129 MRI in human kidneys. Magn. Reson. Med. 83, 262–270 (2020). 10.1002/mrm.27923

6. Venkatesh, A. K. et al. MRI of the lung gas-space at very low-field using hyperpolarized noble gases. Magn. Reson. Imaging 21, 773–776 (2003). 10.1016/S0730-725X(03)00178-4

7. Domingues-Viqueira, William; Juan Parra-Robles; Fox, M. A Variable Field Strength System for Hyperpolarized Noble Gas MR Imaging of Rodent Lungs. Concepts Magn. Reson. Part B Magn. Reson. Eng. 33B, 124–137 (2008). 10.1002/cmr.b.20111

8. Tsai, L. L., Mair, R. W., Rosen, M. S., Patz, S. & Walsworth, R. L. An open-access, very-low-field MRI system for posture-dependent 3He human lung imaging. J. Magn. Reson. 193, 274–285 (2008). 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.05.016

9. Yin, X. et al. Large T1 contrast enhancement using superparamagnetic nanoparticles in ultra-low field MRI. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–10 (2018). 10.1038/s41598-018-30264-5

10. Rodriguez, G. G. & Erro, E. M. Fast iron oxide-induced low-field magnetic resonance imaging. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 54, (2021). 10.1088/1361-6463/abbe4d

11. Waddington, D. E. J., Boele, T., Maschmeyer, R., Kuncic, Z. & Rosen, M. S. High-sensitivity in vivo contrast for ultra-low field magnetic resonance imaging using superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Sci. Adv. 6, (2020). 10.1126/sciadv.abb0998

12. Bryden, N., McHugh, C. T., Kelley, M. & Branca, R. T. Longitudinal nuclear spin relaxation of 129Xe in solution and in hollow fiber membranes at low and high magnetic field strengths.

13. Bryden, N., Antonacci, M., Kelley, M. & Branca, R. T. An open-source, low-cost NMR spectrometer operating in the mT field regime. J. Magn. Reson. 332, 107076 (2021). 10.1016/j.jmr.2021.107076

14. Wolber, J., Cherubini, A., Dzik-Jurasz, A. S. K., Leach, M. O. & Bifone, A. Spin-lattice relaxation of laser-polarized xenon in human blood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 3664–3669 (1999). 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3664

15. Norquay, G. et al. Relaxation and exchange dynamics of hyperpolarized 129Xe in human blood. Magn. Reson. Med. 74, 303–311 (2015). 10.1002/mrm.25417

Figures