4491

Investigating Multi-Dimensional Diffusion-Weighted MRI for High-Resolution Post-Mortem Brain Acquisitions at 9.4 T1Department of Neuropsychology, Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig, Germany, 2Translational Molecular Imaging, German Cancer Research Centre, Heidelberg, Germany, 3Department of Neurophysics, Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig, Germany, 4Paul Flechsig Institute - Center of Neuropathology and Brain Research, Medical Faculty, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany, 5Combinatorial Neuroimaging Core Facility, Leibniz Institute for Neurobiology, Magdeburg, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, ex vivo, human, brain

Diffusion-weighted MRI (dMRI) is a widely used tool to non-invasively study the microstructure of the human brain. However, conventionally employed diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) applications only provide limited information. In contrast, Multi-Dimensional Diffusion Imaging, MD-dMRI, aims to provide a framework for further discrimination between highly complex biological structures. In this context, post-mortem MD-dMRI data play an important role to validate in vivo imaging results. Because the fixation process modifies tissue properties, adapted and optimized acquisition methods are required. Here, we investigate the feasibility to acquire and analyse high-resolution MD-dMRI data from a post-mortem brain tissue sample.

Introduction

Diffusion-weighted MRI (dMRI) allows to non-invasively study the human brain’s microstructure. A common technique to study anisotropic diffusion, e.g., in white matter (WM), is Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) using pulsed dMRI sequences.1 However, due to averaging of microstructure in DTI, diffusion contrasts of complex tissue regions, such as isotropic dispersion of white matter fibres or diffusion of free water, remain indistinguishable.2 This limitation fundamentally restricts the interpretations and results of commonly employed biophysical models.3 In contrast to conventional pulsed dMRI measurements, multidimensional dMRI (MD-dMRI) acquisitions encode multiple diffusion directions simultaneously, generating further microstructural contrast. Combined with a diffusion tensor distribution (DTD) to model microstructural environments as an ensemble of diffusion tensors, biophysical parameters can be extracted by fitting a cumulant expansion approximation to the ensemble-averaged signal data.4 To validate the results and findings of such novel acquisition techniques and biophysical models, comparison with ground truth is crucial. At this point, the importance of post-mortem dMRI arises, as data acquisition, analysis and histological validation can be performed on the same sample.5 Additionally, post-mortem measurements allow high-resolution acquisitions thereby further enhancing anatomical insight. Nevertheless, due to altered diffusion properties of formalin-fixed tissue6, optimized gradient waveforms are required to correctly extract biophysical parameters. This work investigates the applicability of MD Q-Space-Trajectory Imaging (QTI) to post-mortem data acquisitions. To this end, we obtained high-resolution QTI MD-dMRI data from a post-mortem human brain sample at the highest possible quality and reconstructed microstructural parameters derived from the DTD model.Methods

Sample preparation: From a human post-mortem brain (female, 82y, post-mortem interval 24h), immersion fixed in 4%-paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), a tissue block containing the Heschl's gyrus from the left hemisphere was excised. The block was washed in PBS containing 1% sodium azide. For scanning, the sample was embedded in perflourethylether.Data acquisition: MD-dMRI7 data were acquired on a 9.4 T MRI system (Bruker BioSpec 94/20, Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany) with a gradient strength of 660 mT/m, a slew rate of 4570 T/m/s and a Bruker 1H 75/40 volume resonator/coil. A series of pre-scans and numerical simulations were performed to optimize the diffusion-weighting signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) (Fig. 1). High-resolution data were acquired using segmented diffusion-weighted 3D-EPI (Parameters, see Fig. 2). Gradient-direction calculations are based on electrostatic repulsion generalized to multishell acquisitions.8 Diffusion-weighting gradient waveforms were optimized using NOW.9 The dataset comprised 12 interleaved $$$b_{0}$$$-images for potential sample motion and signal drift correction. A noise-map volume was acquired using the same sequence without excitation pulses. The entire data acquisition took 57h.

Data preprocessing: Data noise was characterized from the acquired noise-maps10. Data was denoised11,12, Gibbs ringing corrected13, drift corrected14, and corrected for distortions15. A non-negligible dot-compartment with a diffusion coefficient close to zero16 is expected for post-mortem dMRI due to the presence of immobilized water in biological tissue caused by fixation. The observation of a signal significantly different from zero and plateauing at even high diffusion-weighting validated the motivation to correct for the dot-compartment.

Diffusion modelling: The biophysical DTD model approximates multiple tissue microenvironments in a voxel by a distribution of diffusion tensors4. A second-order cumulant expansion of the conventional signal equation approximates the diffusion-weighted signal $$$S$$$.

$$ S(\textbf{B}) \approx e^{- <\textbf{B}, \textbf{D}> + 0.5 <\textbf{B}^{\otimes 2}, \mathbb{C}>}$$

With the b-tensor $$$\textbf{B}$$$, the average diffusion tensor $$$\textbf{D}$$$ per voxel and the diffusion covariance matrix $$$\mathbb{C}$$$. Several scalars derived from $$$\mathbb{C}$$$ aim to distinguish between variations in sizes, shapes, and orientations of the microenvironments. Voxel-wise DTD fitting was performed on the data for planar b-values up to 56 ms/µm² and linear b-values up to 65 ms/µm².

Results

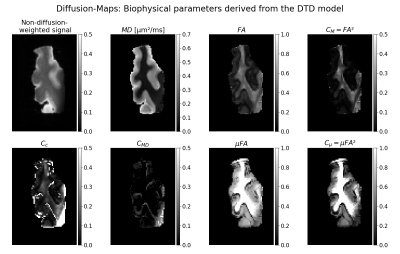

Figure 2 shows the high-resolution data and their DTI-fits to illustrate sample quality. Figure 3 shows diffusion-maps with scalars derived from the DTD framework. Interestingly the DTD model failed to adequately represent the measured MD-dMRI data of the post-mortem brain sample. It hence resulted in partially unphysical determined tissue properties, such as the microscopic fractional anisotropy (µFA), exceeding their normalized boundaries of [0, 1]. Moreover, there is little agreement between the synthesized signals from the DTD-fits and the actual measured signals (Fig. 4). In summary, these results indicate that the second-order cumulant DTD model could not reproduce the diffusion environment of our sample.Conclusion

This work investigated the applicability of the DTD framework to post-mortem MD-dMRI studies. While the acquisition of high-quality MD-dMRI data with high resolution and strong diffusion-weighting is feasible, the DTD model was not able to adequately represent the acquired post-mortem data. This could be due to the commonly used second-order cumulant approximation of the diffusion-weighted signal, which might be violated in fixed tissue due to increased non-Gaussian diffusion caused by immobilized water. Our measurements' high resolution may have also contributed to revealing tissue properties and geometries that are averaged out when using lower resolutions. Fixation processes optimized for diffusion imaging may help to circumvent this problem. Alternatively, an extension of the DTD model to a higher-order cumulant approximation might be helpful. This, however, would require the physical interpretation of higher-order diffusion terms. The impact of these steps will be part of future research, also with larger numbers of post-mortem samples.Acknowledgements

We want to thank the Brain Banking Centre Leipzig of the German Brain-Net, operated by the Paul Flechsig Institute - Center of Neuropathology and Brain Research, Medical Faculty, University of Leipzig, Department of Neuropathology, University Hospital Leipzig, for providing the post-mortem tissue for this study.

References

1. P. J. Basser, J. Mattiello, and D. LeBihan. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys J, vol. 66, no. 1, 1994, doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1.

2. M. Reisert, V. G. Kiselev and B. Dhital. A unique analytical solution of the white matter standard model using linear and planar encodings. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 81(6), 3819–3825. 2019. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27685

3. L. J. O’Donnell and C. F. Westin. An introduction to diffusion tensor image analysis. Neurosurgery Clinics of North America, vol. 22, no. 2. 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2010.12.004.

4. C. F. Westin et al. Q-space trajectory imaging for multidimensional diffusion MRI of the human brain. Neuroimage, vol. 135, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.02.039.

5. A. Yendiki, M. Aggarwal, M. Axer, A. F. D. Howard, A. M. van C. van Walsum, and S. N. Haber. Post mortem mapping of connectional anatomy for the validation of diffusion MRI. Neuroimage, vol. 256, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119146.

6. A. Roebroeck, K. L. Miller, and M. Aggarwal. Ex vivo diffusion MRI of the human brain: Technical challenges and recent advances. NMR in Biomedicine, vol. 32, no. 4. 2019. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3941.

7. Matthew Budde, OSF repository: Preclinical Neuro MRI/MCW Pulse Sequences, https://osf.io/t9vqn/

8. E. Caruyer, C. Lenglet, G. Sapiro, and R. Deriche. Design of multishell sampling schemes with uniform coverage in diffusion MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 69, no. 6, 2013, doi: 10.1002/mrm.24736.

9. F. Szczepankiewicz, C. F. Westin, and M. Nilsson. Gradient waveform design for tensor-valued encoding in diffusion MRI. J Neurosci Methods, vol. 348, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2020.109007.

10. S. St-Jean, A. de Luca, C. M. W. Tax, M. A. Viergever, and A. Leemans. Automated characterization of noise distributions in diffusion MRI data. Med Image Anal, vol. 65, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.media.2020.101758.

11. L. Cordero-Grande, D. Christiaens, J. Hutter, A. N. Price, and J. v. Hajnal. Complex diffusion-weighted image estimation via matrix recovery under general noise models. Neuroimage, vol. 200, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.039.

12. J. Veraart, E. Fieremans, and D. S. Novikov. Diffusion MRI noise mapping using random matrix theory. Magn Reson Med, vol. 76, no. 5, 2016, doi: 10.1002/mrm.26059.

13. T. Bautist, J. O’Muircheartaigh, J. Hajnal, and J. Tournier. Removal of gibbs ringing artefacts for 3d acquisitions using subvoxel shifts. In ISMRM (abstract #3535), 2021.

14. S. B. Vos, C. M. W. Tax, P. R. Luijten, S. Ourselin, A. Leemans, and M. Froeling. The importance of correcting for signal drift in diffusion MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 77, no. 1, pp. 285–299, Jan. 2017, doi: 10.1002/mrm.26124.

15. J. L. R. Andersson and S. N. Sotiropoulos. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage, vol. 125, pp. 1063–1078, Jan. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.019.

16. C. M. W. Tax, F. Szczepankiewicz, M. Nilsson, and D. K. Jones. The dot-compartment revealed? Diffusion MRI with ultra-strong gradients and spherical tensor encoding in the living human brain. Neuroimage, vol. 210, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116534.

Figures

b) Estimated SNR with TE. Increasing the diffusion gradient durations resulted in theoretical TE of 58 ms and an SNR-drop of 293 to 188 in white matter (WM) and 479 to 320 in gray matter (GM). The final SNR at final TE is shown at left. c) Stability assessment of µFA fit per SNR. A DTI-fit of the pre-scan data was used to build synthetic DTDs. The performance of the DTD-fit was tested on different synthetic tissue and with increasing SNR. The variance in parameter estimation is comparably low up to the target SNR.

In general, the whole sample shows high tissue quality without decomposition effects.

Fig. 3: Axial views of the diffusion-maps resulting from the voxel-wise fit of the diffusion tensor distribution model to the post-mortem MD-dMRI data. Each map represents a scalar derived from the average diffusion tensor or the covariance matrix. The fractional anisotropy as well as scalars derived from the covariance matrix ($$$C_{M}, C_{C}, C_{MD}, µFA, C_{mu}$$$) are normalized to [0,1]. Note that the contrast in some of the scalar maps is adjusted to see more details, mainly in parameter maps with comparably low estimated values.