4487

Assessing Sex Differences in the Brain’s White Matter Microstructure during Development using the Tensor Distribution Function1Imaging Genetics Center, Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging & Informatics Institute, University of Southern California, Marina del Rey, CA, United States, 2Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Signal Modeling, Microstructure

Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) can detect sex differences in developmental populations, as shown previously using the conventional diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) model. However, DTI cannot model complex brain fiber orientations, which the advanced tensor distribution function (TDF) model does. Here we compared the two models’ sensitivity in detecting sex differences, with the goal of improving our understanding of WM sex differences during development. We discovered WM microstructure sex effects, with the TDF model detecting more regions with significant differences and yielding larger effect sizes. Our results suggest that TDF is better able to detect developmental sex effects on WM.Introduction

Previous work investigating white matter (WM) microstructure in developmental populations has firmly established the existence of white matter sex differences when using diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI)1-3. These prior studies of WM sex effects in developmental populations have primarily used the conventional diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) model4,5, which is a single-tensor Gaussian model of the dominant tensor in a voxel. The strict Gaussianity of the DTI model is a critical limitation because the brain’s WM contains many complex fiber crossings in a single voxel, and DTI cannot fully characterize WM microstructure in the brain4-7.To address DTI’s inability to account for complex fiber orientations, multiple advanced dMRI models have been developed. One such model is the tensor distribution function (TDF), which is a probabilistic dMRI model composed of a continuous mixture of Gaussians8,9. This model assigns weights to a probabilistic ensemble of tensors for each voxel and uses the least-squares principle and gradient descent algorithms to find the optimal TDF for the voxel. The diffusion metric that is produced by TDF is fractional anisotropy (FATDF), which is comparable to DTI’s FA value (FADTI) but accurately accounts for complex fiber orientations in the brain. Previous work in Alzheimer’s disease10, normative aging in middle to late adulthood11, and cognitive impairment12 has found that FATDF was more sensitive than FADTI to WM differences, further reflecting the utility of TDF. Additionally, unlike many advanced dMRI models but similar to DTI, TDF can be applied to single-shell dMRI data. Thus, TDF can be used with archival dMRI scans, allowing for increased sample sizes when studying WM microstructure.

Prior work in older adults has shown significant sex differences in WM microstructure when using the TDF model11. However, no work to date has investigated sex differences in developmental populations using TDF. The current investigation therefore used the dMRI models DTI and TDF to assess sex differences in WM microstructure during development and determine which model is more sensitive to such sex effects. We hypothesized that TDF would capture such sex effects on WM microstructure differences more sensitively, as it can model more complex fiber orientations than DTI.

Methods

We analyzed dMRI scans from 115 typically developing subjects (49.5% female; age: 5-21 years). The scans were from the open-source Healthy Brain Network database13, which includes 4 different scan sites. Briefly, three of the sites used two shells (b=1000 and 2000 s/mm2) and one site used a single shell (b=1000 s/mm2), with each shell using 64 distinct directions; for consistency, only the b=1000 s/mm2 shell was used in this investigation2,3,11. The DTI metrics calculated were FADTI, and mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD); for the TDF model, FATDFwas calculated. We used the ENIGMA DTI protocol (http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/protocols/dti-protocols), which uses tract based spatial statistics (TBSS) to create WM skeletons14,15. The average of each diffusion metric was then calculated for 20 deep WM regions of interest (ROI) from the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) DTI atlas16. To correct for inter-scanner variability, the harmonization method ComBat was used. We included demeaned age and age2 as nuisance covariates in our linear fixed effects model. FDR was used to correct for multiple comparisons across ROIs.Results

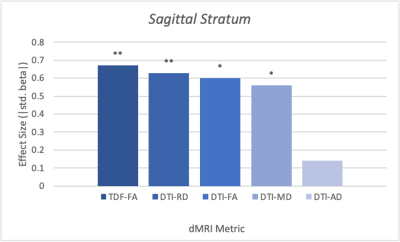

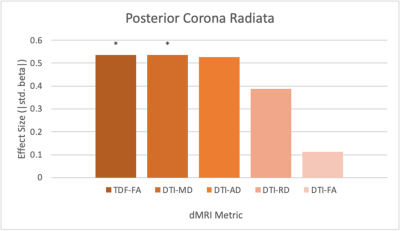

The diffusion metrics FADTI, FATDF, MD and RD displayed significant alterations of WM microstructure between the sexes. The sagittal stratum (SS) was significantly different between males and females across these metrics (FADTI: p=.03, β=0.60 FATDF: p=.006, β=0.67; MD: p=.02, β=0.60; RD: p=.005, β=0.63). The posterior corona radiata (PCR) also showed significant differences in FATDF and MD (FATDF: p=.03, β=0.54; MD: p=.02, β=0.54). FATDF also exhibited significant sex differences in a number of ROIs that did not significantly differ in any of the DTI metrics, including the external capsule (EC) (p=.03, β=0.46), fornix/stria terminalis (FXST) (p=.03, β=0.52), posterior thalamic radiation (PTR) (p=.03, β=0.47), splenium of corpus collosum (SCC) (p=.03, β=0.54), superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) (p=.03, β=0.45).For the ROIs that were significant for at least one metric in both models, FATDF showed an effect size that was either larger or similar in magnitude to the DTI metric with the largest effect size. TDF also showed significance in five additional ROIs that were not significant in the DTI model: the EC, FXST, PTR, SCC, and SLF.

Discussion

Both DTI and TDF detected significant sex differences in WM microstructure, but effect sizes for TDF were similar or greater than those for DTI. The TDF model captured regionally specific differences in WM that DTI did not. TDF may be more powerful than DTI for studying sex effects in developmental populations. Further investigation of sex differences in development using the TDF model will advance our understanding of WM microstructure in this population, which in turn may be useful for studying neuropsychiatric disorders that emerge during adolescence and exhibit significant sex differences in prevalence.Acknowledgements

NIMH Grant R01MH116147 to P.M.T.

NIMH Grant F32MH122057 to K.E.L.

References

1. Lawrence, K. E., Abaryan, Z., Laltoo, E., Hernandez, L. M., Gandal, M., McCracken, J. T., & Thompson, P. M. (2022). White matter microstructure shows sex differences in late childhood: Evidence from 6,797 children (p. 2021.08.19.456728). bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.19.456728

2. Kaczkurkin, A. N., Raznahan, A., & Satterthwaite, T. D. (2019). Sex differences in the developing brain: Insights from multimodal neuroimaging. Neuropsychopharmacology, 44(1), Article 1.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0111-z

3. Tamnes, C. K., Roalf, D. R., Goddings, A.-L., & Lebel, C. (2018). Diffusion MRI of white matter microstructure development in childhood and adolescence: Methods, challenges and progress. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 33, 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2017.12.002

4. Basser, P. J., Mattiello, J., & LeBihan, D. (1994a). MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophysical Journal, 66(1), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1

5. Basser, P. J., Mattiello, J., & Lebihan, D. (1994b). Estimation of the Effective Self-Diffusion Tensor from the NMR Spin Echo. Journal of Magnetic Resonance, Series B, 103(3), 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmrb.1994.1037

6. Alexander, A. L., Lee, J. E., Lazar, M., & Field, A. S. (2007). Diffusion Tensor Imaging of the Brain. Neurotherapeutics, 4(3), 316–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.011

7. Jones, D. K. (2008). Studying connections in the living human brain with diffusion MRI. Cortex, 44(8), 936–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2008.05.002

8. Leow, A. D., Zhu, S., Zhan, L., McMahon, K., de Zubicaray, G. I., Meredith, M., Wright, M. J., Toga, A. W., & Thompson, P. M. (2009). The tensor distribution function. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 61(1), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.21852

9. Zhan, L., Leow, A. D., Zhu, S., Barysheva, M., Toga, A. W., McMahon, K. L., de Zubicaray, G. I., Wright, M. J., & Thompson, P. M. (2009). A Novel Measure of Fractional Anisotropy Based on the Tensor Distribution Function. In G.-Z. Yang, D. Hawkes, D. Rueckert, A. Noble, & C. Taylor (Eds.), Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2009 (pp. 845–852). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-04268-3_104

10. Nir, T. M., Jahanshad, N., Villalon-Reina, J. E., Isaev, D., Zavaliangos-Petropulu, A., Zhan, L., Leow, A. D., Jack Jr., C. R., Weiner, M. W., Thompson, P. M., & Initiative (ADNI), for the A. D. N. (2017). Fractional anisotropy derived from the diffusion tensor distribution function boosts power to detect Alzheimer’s disease deficits. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 78(6), 2322–2333. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26623

11. Lawrence, K. E., Nabulsi, L., Santhalingam, V., Abaryan, Z., Villalon-Reina, J. E., Nir, T. M., Ba Gari, I., Zhu, A. H., Haddad, E., Muir, A. M., Laltoo, E., Jahanshad, N., & Thompson, P. M. (2021). Age and sex effects on advanced white matter microstructure measures in 15,628 older adults: A UK biobank study. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 15(6), 2813–2823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-021-00548-y

12. Zavaliangos-Petropulu, A., Nir, T. M., Thomopoulos, S. I., Reid, R. I., Bernstein, M. A., Borowski, B., Jack Jr., C. R., Weiner, M. W., Jahanshad, N., & Thompson, P. M. (2019). Diffusion MRI Indices and Their Relation to Cognitive Impairment in Brain Aging: The Updated Multi-protocol Approach in ADNI3. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, 13. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fninf.2019.00002

13. Alexander, L. M., Escalera, J., Ai, L., Andreotti, C., Febre, K., Mangone, A., Vega-Potler, N., Langer, N., Alexander, A., Kovacs, M., Litke, S., O’Hagan, B., Andersen, J., Bronstein, B., Bui, A., Bushey, M., Butler, H., Castagna, V., Camacho, N., … Milham, M. P. (2017). An open resource for transdiagnostic research in pediatric mental health and learning disorders. Scientific Data, 4(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.181

14. Jahanshad, N., Kochunov, P. V., Sprooten, E., Mandl, R. C., Nichols, T. E., Almasy, L., Blangero, J., Brouwer, R. M., Curran, J. E., de Zubicaray, G. I., Duggirala, R., Fox, P. T., Hong, L. E., Landman, B. A., Martin, N. G., McMahon, K. L., Medland, S. E., Mitchell, B. D., Olvera, R. L., … Glahn, D. C. (2013). Multi-site genetic analysis of diffusion images and voxelwise heritability analysis: A pilot project of the ENIGMA–DTI working group. NeuroImage, 81, 455–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.061

15. Smith, S. M., Jenkinson, M., Johansen-Berg, H., Rueckert, D., Nichols, T. E., Mackay, C. E., Watkins, K. E., Ciccarelli, O., Cader, M. Z., Matthews, P. M., & Behrens, T. E. J. (2006). Tract-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. NeuroImage, 31(4), 1487–1505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024

16. Mori, S., Oishi, K., Jiang, H., Jiang, L., Li, X., Akhter, K., Hua, K., Faria, A. V., Mahmood, A., Woods, R., Toga, A. W., Pike, G. B., Neto, P. R., Evans, A., Zhang, J., Huang, H., Miller, M. I., van Zijl, P., & Mazziotta, J. (2008). Stereotaxic white matter atlas based on diffusion tensor imaging in an ICBM template. NeuroImage, 40(2), 570–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.035