4480

Investigating Diffusion Time Dependent Kurtosis Evolution in Repeated Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice1Department of Medical Biophysics, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada, 2Centre for Functional and Metabolic Mapping (CFMM), Robarts Research Institute, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada, 3Translational Neuroscience Group, Robarts Research Institute, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada, 4Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Microstructure, mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI); Concussion

Probing the diffusion time dependence of diffusional kurtosis within brain microstructure is being recognized as a valuable method to study various neurological pathologies, however, its use in the study of repeated mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) has not been explored. In this work, we investigated differences in the time-dependence of diffusional kurtosis in injured and sham mice using oscillating gradient spin echo (OGSE) diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI). The results of this work show promising differences in kurtosis within the hippocampus of injured and sham mice, illustrating the sensitivity of OGSE DKI in detecting long-lasting pathological microstructural changes following brain injury.Introduction

Diffusion MRI (dMRI) is a powerful tool for studying brain pathology on a spatial scale not visible to conventional MRI. Oscillating gradient spin echo (OGSE) dMRI allows us to probe at much shorter effective diffusion times than possible with traditional pulsed gradient spin echo (PGSE) dMRI. By varying the gradient oscillation frequency used during a single acquisition sequence, we can probe tissue microstructure at various spatial scales, exploiting the diffusion time dependency in the brain. Also, diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) extends from the traditional diffusion tensor model in a separate manner from OGSE by quantifying the non-gaussian behavior of water diffusion. Previous work has shown frequency dependent kurtosis changes in hypoxic ischemic insult1, however, whether OGSE kurtosis is sensitive to microstructural changes that occur following mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) has not been explored. The aim of this study is to determine if OGSE DKI is sensitive to long-term neurobiological changes that occur following repeated mTBI.Methods

Subjects: 8 mice (6 male and 2 females, age range of 5-6 months at baseline) carrying humanized versions of amyloid precursor and tau proteins were scanned 1-2 weeks prior to injury and again 6 months after injury. 4 of these mice (3 male and 1 female) underwent mTBI using a controlled cortical impactor on 3 consecutive days, with remaining mice serving as a control group.MRI Acquisition: dMRI and T2-weighted images were acquired on a 9.4 Tesla Bruker small animal scanner. The dMRI protocol included PGSE (i.e., 0 Hz) and OGSE with frequencies of 60 and 120 Hz, using b-values of 28 (6 averages), 1025 (10 directions) and 2450 (10 directions) s/mm2. The dMRI protocol was acquired in one integrated scan using single-shot echo-planar-imaging (EPI) with parameters: in-plane resolution 200x200 μm2, slice thickness 500 μm, TE/TR = 35.5/15000 ms, total scan time of 66 minutes. Anatomical images were acquired during each imaging session using a T2-weighted TurboRARE sequence with parameters: in-plane resolution 100x100 μm2, slice thickness 500 μm, TE/TR = 30/5500 ms, total scan time of 10 minutes.

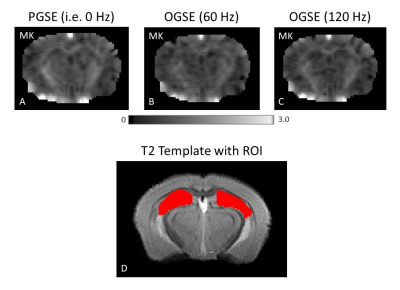

dMRI Data Analysis: Complex-valued averages were combined using in-house MATLAB code which included partial Fourier reconstruction, correction for frequency drift, and denoising2, similar to earlier work3. Kurtosis maps from each imaging session were generated using in-house MATLAB code. A multi-slice hippocampus region-of-interest (ROI) was drawn manually on a T2 template created with Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) software4, to which all kurtosis maps were registered to. Mean kurtosis (MK) was quantified at each frequency by applying the ROI to the corresponding kurtosis map. ΔMK for each mouse and timepoint was calculated by subtracting the MK within the ROI at 0 Hz by MK at 120 Hz.

Results

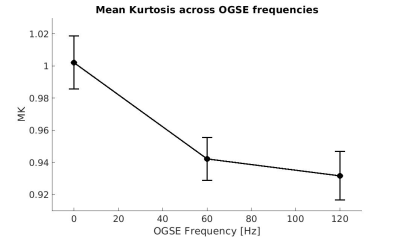

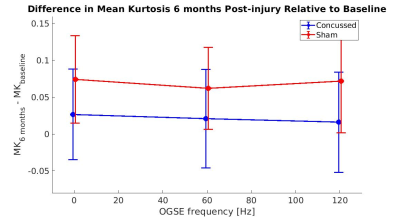

Figure 1 shows MK maps from one representative mouse brain along with the anatomical template. When averaging MK measurements within the hippocampus from all mice at both timepoints, we found a decrease in MK when using higher OGSE frequencies (f=0 Hz: mean (M)=1.02 +/- 0.02 SEM, f=60 Hz: M=0.94 +/- 0.01, f=120 Hz: M=0.93 +/- 0.02) (Figure 2). In the sham group, we see increased MK at 6 months relative to baseline at all frequencies (f=0 Hz: ΔMs=0.0741, f=60 Hz: ΔMs=0.0620, f=120 Hz: ΔMs=0.0719). In the concussion group, we also see increased MK at 6 months relative to baseline (f=0 Hz: ΔMc=0.0265, f=60 Hz: ΔMc=0.0208, f=120 Hz: ΔMc=0.0163), however, these increases were smaller relative to the sham group (Figure 3). Using ΔMK calculated for each mouse at both timepoints, we see a matching increase in MK in both groups at 6 months relative to baseline (Figure 4).Discussion

This preliminary study shows evidence for differences in OGSE kurtosis between concussed and sham groups. While low cohort sizes are currently a limitation, the study is ongoing to increase sample sizes. The trend of decreasing MK at higher OGSE frequencies has been found by many previous studies1,5,6. We show a trend of increased MK at 6 months in the sham group, while showing a smaller increase in MK in the concussed group. Previous PGSE DKI studies show a similar trend of decreased MK in concussion compared to sham groups in the months post-injury7-9. We suspect that increased kurtosis in the sham group is due to increased myelination and dendritic arborization known to occur in healthy development due to learning and memory consolidation in the hippocampus10,11. Notably, previous DKI studies have suggested that both myelination12 and dendritic arborizations13 result in increased kurtosis. Based on the trend of decreased kurtosis in the concussion group relative to control found here and in previous work7-9, we speculate that repeated mTBI may induce long-term impairment of myelination and arborization processes. However, because multiple neurobiological changes can impact the dMRI contrast, we cannot exclude other pathological mechanisms leading to the trend we observe. Regardless, we show here that diffusion time dependent DKI may be sensitive to long-term changes that occur due to repeated mTBI.Conclusion

In this research, the use of OGSE DKI was demonstrated for the study of long-term changes following repeated mTBI. Examining the diffusion time dependency of kurtosis measurements will give further insight into neurobiological changes that occur following mTBI, allowing for pathological sequelae to be further elucidated.Acknowledgements

This project is partially supported by US Department of Defense under congress-directed medical research program (CDMRP), Peer Reviewed Alzheimer’s Research Program (PRARP) by award# W81XWH-20-1-0323.References

1. Wu, D., Li, Q., Northington, F. J. & Zhang, J. Oscillating gradient diffusion kurtosis imaging of normal and injured mouse brains. NMR Biomed. 2018;31:e3917.

2. Veraart, J. et al. Denoising of diffusion MRI using random matrix theory. Neuroimage. 2016;142:394-406.

3. Rahman, N. et al. Test-retest reproducibility of in vivo oscillating gradient and microscopic anisotropy diffusion MRI in mice at 9.4 Tesla. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255711.

4. Avants, B. B. et al. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2033-44.

5. Lee, H.-H., Papaioannou, A., Novikov, D. S. & Fieremans, E. In vivo observation and biophysical interpretation of time-dependent diffusion in human cortical gray matter. Neuroimage. 2020;222:117054. 6. Aggarwal, M., Smith, M. D. & Calabresi, P. A. Diffusion‐time dependence of diffusional kurtosis in the mouse brain. Magn Reson Med. 2020;84:1564-1578.

7. Stenberg, J. et al. Diffusion Tensor and Kurtosis Imaging Findings the First Year Following Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma. 2022; doi:10.1089/neu.2022.0206.

8. Karlsen, R. H. et al. Diffusion kurtosis imaging in mild traumatic brain injury and postconcussional syndrome. J Neurosci Res 2019;97:568-581.

9. Wang M-L, Wei X-E, Yu M-M, Li W-B. Cognitive impairment in mild traumatic brain injury: a diffusion kurtosis imaging and volumetric study. Acta Radiologica. 2022;63(4):504-512.

10. Kato, D. & Wake, H. Myelin plasticity modulates neural circuitry required for learning and behavior. Neurosci Res. 2021;167:11-16.

11. Tronel, S. et al. Spatial learning sculpts the dendritic arbor of adult-born hippocampal neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:7963-7968.

12. Kelm, N. D. et al. Evaluation of diffusion kurtosis imaging in ex vivo hypomyelinated mouse brains. Neuroimage. 2016;124:612-626.

13. McKenna, F., Miles, L., Donaldson, J., Castellanos, F. X. & Lazar, M. Diffusion kurtosis imaging of gray matter in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Sci Rep. 2020;10:21465.

Figures