4464

Impact of mitral valve repair on left atrial fibrosis in severe mitral valve regurgitation patients: a 3D LGE pilot follow-up study.1Cardiothoracic Surgery, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2Cardiology, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 3Cardiothoracic Surgery, LUMC, Leiden, Netherlands, 4Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Valves, Valves, Fibrosis

Timing of mitral valve repair (MVR) surgery in mitral valve regurgitation (MR) patients remains a subject of debate. Assessment of left atrial (LA) fibrosis might aid to improve clinical management of these patients. We assessed LA fibrosis extent using 3-dimensional late gadolinium enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging prior to and after MVR surgery in MR patients (n=6). Our data demonstrates a decrease of LA volume, while a concomitant increase in LA fibrosis was observed. Further study is required to determine the potential relation between LA fibrosis, pre- and post-operative changes and long-term clinical outcome.Introduction

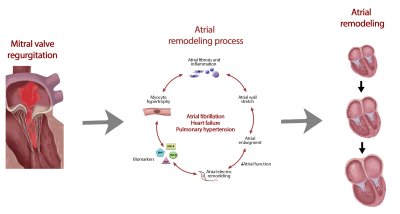

Patients with mitral valve regurgitation (MR) frequently suffer from left atrial (LA) dilatation, caused by volume overload1. The associated myocardial stretch, increased wall tension and involved neurohumoral modulators are considered to trigger a cascade of pathways, ultimately leading to the formation of atrial fibrosis as part of the remodeling process (Figure 1). Presence of atrial fibrosis is associated with an increased risk of adverse events including atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure2. However, the presence of atrial fibrosis in MR patients has not been studied systematically.Surgical mitral valve repair (MVR) remains the ultimate treatment for patients suffering from severe MR and often leads to reversed LA remodeling. Timing of surgery is crucial to avoid progression of LA remodeling, which is associated with worse outcome and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality3. To date, stratification and timing of surgical MVR are based on severity of MR, presence of symptoms and/or severity of left ventricular dilatation and/or dysfunction4. However, accurate timing of surgery in MR patients still remains a subject of debate5,6.

Recent guidelines, therefore, suggest to take LA remodeling (volume) in account for clinical stratification of these patients7. Although atrial fibrosis is a well-recognized marker of LA remodeling, this tissue characteristic, however, is currently not used for clinical decision making and patient stratification for MVR surgery8,9.

The last decade, high spatial resolution 3-dimensional (3D) late gadolinium enhanced (LGE) cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging has emerged as a noninvasive tool for the visualization and quantification of LA fibrosis in AF patients10. In this study, we aim to study the presence and amount of LA fibrosis in MR patients, and to determine the impact of MVR on atrial tissue characteristics, as provided by 3D LGE CMR imaging.

Methods

Patients with chronic severe degenerative MR and without documented AF, who meet the criteria for MVR surgery4, were included in this prospective single center pilot study. Subjects underwent CMR imaging two weeks prior to surgery to identify presence and amount of LA fibrosis. Three months after MVR surgery, all subjects underwent follow-up CMR imaging to assess postoperative LA reversed-remodeling changes including fibrosis.Scans were performed using a 1.5 Tesla CMR system with 32-channel coil coil (Sola scanner, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Acquisition parameters were as follows; repetition time 5.5 ms; echo time 3.0 ms; flip angle 25°; in-plane resolution 1.25 × 1.25 mm; slice thickness 2.5 mm10.

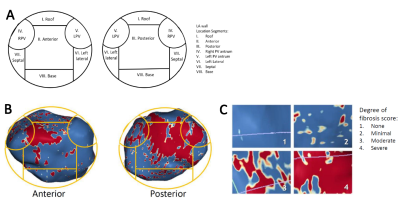

The 3D LGE images were analyzed using ADAS 3D software (Galgo Medical, Barcelona, Spain) to determine the amount of atrial fibrosis. An image intensity ratio of 1.2 was used as threshold to distinguish between healthy myocardium and fibrosis11. A 8-segment model was applied to quantify the regional distribution of LA fibrosis (Figure 2). For statistical analysis, non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank testing was performed.

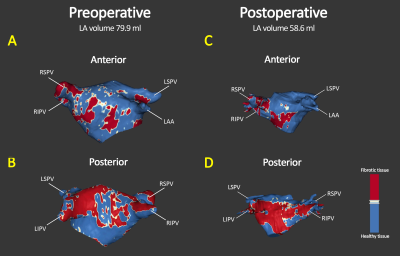

Figure 3 shows an example of segmental LA fibrosis analysis. The LA wall is segmented for accurate geometric localization of fibrosis and the severity of fibrosis is shown as quantified surface area (cm2 and % of total LA volume).

Results

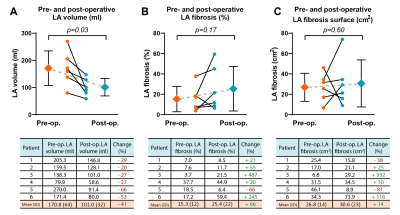

In total 6 patients eligible for MVR surgery were studied (mean age 70±5 years, 86% male). Preoperative LA volume was 171±64 ml, LA fibrosis surface area 27±14 cm2 and LA fibrosis percentage 15±12%. Postoperative assessment showed a significant reduction of LA volume (101±32 ml, p=0.03), and an increase in mean LA fibrosis surface area (31±23 cm2, p=0.6) and LA fibrosis percentage 25±22% (p=0.17) (Figure 4 and 5).Discussion

In this pilot study, a significant reduction in LA volume was found in MR patients following MVR surgery. This postoperative reversed LA remodeling is in line with previous studies12-14. LA fibrotic surface, however, increased at follow-up. Although not significant, this resulted in an average increase of +14% net LA fibrotic surface compared to the preoperative state (Figure 4C).A consistent decrease of LA volume and relative increase of LA fibrosis surface is observed, except for one patient (figure 4B). This particular patient showed extreme left atrial dilatation (LA volume 270 ml) which might have resulted in an overestimation of LA fibrosis at baseline due to extreme wall thinning caused by severely increased wall stress, and associated partial volume effects. When excluding this patient, results show a significant postoperative increase in LA fibrosis percentage (p=0.04).

Remarkable is furthermore that patient 1 showed a decrease in LA fibrosis surface and at the same time an increase in LA fibrosis percentage (Figure 4B and 4C). This is most probably due to a less proportionate decrease of the corresponding LA volume.

This pilot study showed a decrease of LA volume and increase of LA fibrosis in the majority of MR patients undergoing MVR surgery. A larger study is required to assess the relationship between the amount of LA fibrosis and clinical outcomes and whether LA fibrosis may contribute to improved selection and stratification of candidates eligible for MVR.

Conclusion

1. LA fibrosis can be found in patients suffering from severe degenerative MR.2. In case of reversed LA remodeling, the decrease in LA volume is larger than the decrease in percentage LA fibrosis, resulting in a net increase of LA fibrotic surface area.

3. Paradoxically, reversed remodeling may cause an increased amount of LA fibrotic tissue.

Acknowledgements

None.References

1. Cameli M, Lisi M, Righini FM, Massoni A, Natali BM, Focardi M, et al. Usefulness of atrial deformation analysis to predict left atrial fibrosis and endocardial thickness in patients undergoing mitral valve operations for severe mitral regurgitation secondary to mitral valve prolapse. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(4):595-601.

2. King JB, Azadani PN, Suksaranjit P, Bress AP, Witt DM, Han FT, et al. Left Atrial Fibrosis and Risk of Cerebrovascular and Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(11):1311-21.

3. Essayagh B, Antoine C, Benfari G, Messika-Zeitoun D, Michelena H, Le Tourneau T, et al. Prognostic Implications of Left Atrial Enlargement in Degenerative Mitral Regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(7):858-70.

4. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, De Bonis M, Hamm C, Holm PJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease (vol 38, pg 2739, 2017). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(21):1980-.

5. Ling LH, EnriquezSarano M, Seward JB, Orszulak TA, Schaff HV, Bailey KR, et al. Early surgery in patients with mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflets - A long-term outcome study. Circulation. 1997;96(6):1819-25.

6. Zilberszac R, Heinze G, Binder T, Laufer G, Gabriel H, Rosenhek R. Long-Term Outcome of Active Surveillance in Severe But Asymptomatic Primary Mitral Regurgitation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(9):1213-21.

7. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. EuroIntervention. 2022;17(14):e1126-e96.

8. Thomas L, Abhayaratna WP. Left Atrial Reverse Remodeling: Mechanisms, Evaluation, and Clinical Significance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(1):65-77.

9. Jalife J, Kaur K. Atrial remodeling, fibrosis, and atrial fibrillation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25(6):475-84.

10. Hopman L, Bhagirath P, Mulder MJ, Eggink IN, van Rossum AC, Allaart CP, et al. Quantification of left atrial fibrosis by 3D late gadolinium-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients with atrial fibrillation: impact of different analysis methods. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23(9):1182-90.

11. Bertelsen L, Alarcon F, Andreasen L, Benito E, Olesen MS, Vejlstrup N, et al. Verification of threshold for image intensity ratio analyses of late gadolinium enhancement magnetic resonance imaging of left atrial fibrosis in 1.5T scans. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;36(3):513-20.

12. Marsan NA, Maffessanti F, Tamborini G, Gripari P, Caiani E, Fusini L, et al. Left atrial reverse remodeling and functional improvement after mitral valve repair in degenerative mitral regurgitation: a real-time 3-dimensional echocardiography study. Am Heart J. 2011;161(2):314-21.

13. Machado LR, Meneghelo ZM, Le Bihan DC, Barretto RB, Carvalho AC, Moises VA. Preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction and left atrium reverse remodeling after mitral regurgitation surgery. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2014;12:45.

14. Antonini-Canterin F, Beladan CC, Popescu BA, Ginghina C,

Popescu AC, Piazza R, et al. Left atrial remodelling early after mitral valve

repair for degenerative mitral regurgitation. Heart. 2008;94(6):759-64.

Figures