4457

Framework for Characterizing in vivo Passive Myocardial Stiffness using in vivo MRI1Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Radiology, Veterans Administration Health Care System, Palo Alto, CA, United States, 3Mechanical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 4Bioengineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Myocardium, In Silico, computational modeling; inverse finite element modeling

As increased passive myocardial stiffness is implicated in the etiology of many cardiac diseases, its in vivo estimation can improve management of heart disease. MRI-driven computational constitutive modeling can be used to obtain subject-specific passive myocardial stiffness. We present a method for building an in silico model to estimate subject-specific passive myocardial stiffness by combining LV geometric data derived from cine bSSFP, regional kinematics extracted from tagged MRI, and myocardial microstructure measured using in vivo cDTI. This project aims to develop a clinically translatable in vivo passive myocardial stiffness evaluation framework by integrating cardiac MRI and computational modeling.

Introduction

Altered passive myocardial stiffness contributes to the pathophysiology of many cardiac diseases [1]. Consequently, a clinically viable method for its reliable identification could improve management of heart disease. Cardiac MRI and hemodynamic data can be combined to develop personalized inverse finite element models for estimating in vivo passive myocardial stiffness [2].The subject-specific MRI data needed to estimate passive myocardial stiffness are best acquired using cardiac surface geometry from cine bSSFP images, diastolic local kinematics estimated using cine DENSE or tagging, and cardiac microstructural organization measured with cardiac diffusion tensor imaging. However, few studies have combined in vivo cine bSSFP, tagged MRI, and cDTI for estimating subject-specific passive myocardial stiffness partly due to the lack of comprehensive, high fidelity datasets. Moreover, incorporating all this data into one patient-specific in silico model presents a challenge owing to the multiple data sources that may be acquired at different cardiac phases.

The aims of this work were to: (1) acquire, in a healthy volunteer, high fidelity in vivo MRI data needed for passive myocardial stiffness estimation; (2) use this data to develop an in silico model of the subject’s left ventricle (LV); and (3) use the local diastolic kinematics (motion) to calibrate the in silico model and estimate the material parameters through inverse finite element modeling.

Methods

Image AcquisitionImaging was performed on a 3T scanner (Siemens, Skra). A short axis stack of cine bSSFP images were acquired, (TE/TR=1.49/35.0ms; FA=35º; resolution=1×1×6mm3) after which three long axis images were acquired. Then a short axis stack of grid tagged images was acquired (TE/TR=3.01/31.50ms; FA=12º; resolution=1×1×6mm3, 10mm tag spacing), as well as three line tagged long axis slices. Motion compensated cardiac diffusion tensor images (cDTI; TE/TR=86/310ms; resolution=2×2×8mm3; 10 diffusion directions) were then acquired during end systole. The cDTI data was distortion corrected [3], then diffusion tensors were reconstructed.

Reference geometric model

The cardiac geometry used to construct the reference (stress free) finite element mechanics model was chosen at the beginning of atrial systole [4] as determined by the mitral valve motion from the long axis cine images. From this cardiac phase, the LV was segmented and then used to generate the reference geometric models that were used for in silico modeling.

Kinematics

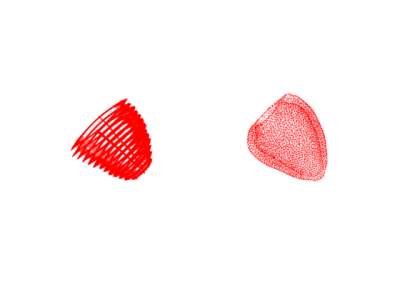

The grid tagged images were tracked with a neural-net based algorithm, which produced displacement curves for tag line intersections [5]. Points were tracked from a reference frame at the beginning of atrial systole, and displacements were used to generate deformation gradient tensors.

Microstructural organization

The LV myocardium was segmented from the short axis slices and the end-systolic mask was used to generate a geometric model. We obtained the primary diffusion eigenvectors in the cDTI image dataset and used them to help define the local material coordinate system for in silico modeling.

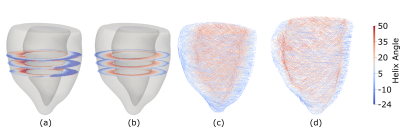

A fit of the transmural variation in cDTI helix angle across all slices was performed. From this fit, we obtained patient-specific endocardial and epicardial helix angles that were subsequently used to constrain the epicardial and endocardial boundaries of a smooth rule-based fiber field in the end-systolic geometric model [6].

The systolic fiber orientations were then reoriented to their diastasis configurations using the deformation gradient tensors between the two phases. Following this, a 3D description of the fiber orientation in diastasis was obtained and was subsequently incorporated into the in silico model.

LV Finite Element Model

The 3D geometric model of the LV in the reference configuration was used to generate a volumetric quadratic tetrahedral mesh of average edge size 3mm [7]. Myocardial incompressibility [8] was enforced in the simulation.

Diastolic filling was simulated by applying an endocardial pressure boundary condition to passively inflate the LV. In the absence of in vivo LV cavity pressure recordings, we simulated passive inflation using an end-diastolic pressure of 1.5 kPa from literature [9,10].

The experimentally derived LV nodal displacements were used to inversely estimate the material parameters of the Guccione transversely isotropic myocardial material law [11]. After an initial guess, we iteratively updated the model’s underlying constitutive parameters (FEBio,[12]) to minimize the mismatch between the experimentally measured nodal displacements (from tagged MRI) and the simulated pressure-induced nodal displacements.

Results

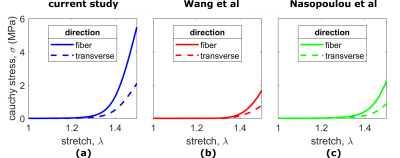

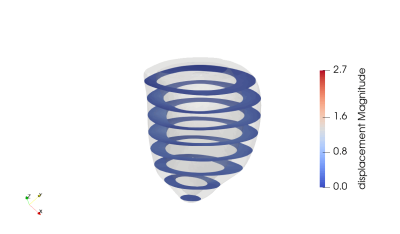

The averaged endocardial and epicardial helix angles were 42º and -16º in systole and 50º and -24º in diastasis after reorientation (Fig.2). The stress-strain relation of the optimized material law in biaxial extension is shown and compared with results of studies on the passive diastolic mechanical behavior of human myocardium from literature [13,14] (Fig.4). We also show the simulated LV inflation and depict the spatial variation in displacement magnitude (Fig.5).Conclusion

We used cine bSSFP (surface data), tagged MRI (kinematics), and cDTI (in vivo microstructure) to develop an in silico model for estimating subject-specific passive myocardial stiffness. We also presented preliminary results of our passive myocardial material parameter optimization that are consistent with prior work. Given the sensitivity of mechanical behavior to the spatial distribution of fiber orientation [15], we believe the results are affected by our measured helix angles which differ from expected values [16,17]. Future work will focus on extensive validation and model sensitivity analysis to understand the uncertainty in results.Acknowledgements

Project support: NIH R01 HL131823 to DBEReferences

1. Kass, D.A., Bronzwaer, J.G.F., Paulus, W.J., 2004. What mechanisms underlie diastolic dysfunction in heart failure? Circulation Research 94, 1533–1542.

2. Wang, V.Y., Nielsen, P.M.F., Nash, M.P., 2015. Image-Based Predictive Modeling of Heart Mechanics. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 17, 351–383.

3. Andersson, J.L.R., Skare, S., Ashburner, J., 2003. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage 20, 870–888.

4. Shmuylovich, L., Chung, C.S., Kovács, S.J., 2010. Point: Left ventricular volume during diastasis is the physiological in vivo equilibrium volume and is related to diastolic suction. J Appl Physiol (1985) 109, 606–608.

5. Loecher, M., Perotti, L.E., Ennis, D.B., 2021. Using synthetic data generation to train a cardiac motion tag tracking neural network. Medical Image Analysis 74, 102223.

6. Bayer, J.D., Blake, R.C., Plank, G., Trayanova, N.A., 2012. A Novel Rule-Based Algorithm for Assigning Myocardial Fiber Orientation to Computational Heart Models. Ann Biomed Eng 40, 2243–2254.

7. Geuzaine, C., Remacle, J.-F., 2009. Gmsh: A 3-D finite element mesh generator with built-in pre- and post-processing facilities. Int J Numer Methods Eng 79, 1309–1331.

8. Holzapfel, G.A., Ogden, R.W., 2009. Constitutive modelling of passive myocardium: a structurally based framework for material characterization. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 367, 3445–3475.

9. Nasopoulou, A., Shetty, A., Lee, J., Nordsletten, D., Rinaldi, C.A., Lamata, P., Niederer, S., 2017. Improved identifiability of myocardial material parameters by an energy-based cost function. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 16, 971–988.

10. Humphrey J.D., 2002. Cardiovascular solid mechanics. Springer, New York

11. Guccione, J.M., McCulloch, A.D., Waldman, L.K., 1991. Passive material properties of intact ventricular myocardium determined from a cylindrical model. J Biomech Eng 113, 42–55.

12. Maas, S.A., Ellis, B.J., Ateshian, G.A., Weiss, J.A., 2012. FEBio: Finite Elements for Biomechanics. J Biomech Eng 134, 11005.

13. Wang, Z.J., Wang, V.Y., Bradley, C.P., Nash, M.P., Young, A.A., Cao, J.J., 2018. Left Ventricular Diastolic Myocardial Stiffness and End-Diastolic Myofibre Stress in Human Heart Failure Using Personalised Biomechanical Analysis. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 11, 346–356.

14. Nasopoulou, A., Shetty, A., Lee, J., Nordsletten, D., Rinaldi, C.A., Lamata, P., Niederer, S., 2017. Improved identifiability of myocardial material parameters by an energy-based cost function. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 16, 971–988.

15. Rijcken, J., Bovendeerd, P.H.M., Schoofs, A.J.G., van Campen, D.H., Arts, T., 1999. Optimization of Cardiac Fiber Orientation for Homogeneous Fiber Strain During Ejection. Annals of Biomedical Engineering 27, 289–297.

16. Geerts, L., Bovendeerd, P., Nicolay, K., Arts, T., 2002. Characterization of the normal cardiac myofiber field in goat measured with MR-diffusion tensor imaging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283, H139-145.

17. Arts, T., Costa, K.D., Covell, J.W., McCulloch, A.D., 2001. Relating myocardial laminar architecture to shear strain and muscle fiber orientation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280, H2222-2229.

Figures

Figure 1: Animation of a mid-ventricular slice of the subject in vivo tagged MRI (left) and cine bSSFP (right). Both images were acquired with 1×1×6 mm3 spatial resolution and 25 phases were acquired throughout the cardiac cycle with 6 end-diastolic frames (during passive inflation)

Figure 2: (a) Helix angle maps from in vivo cDTI. (b) Rule-based fit (weighted by fractional anisotropy) to measured helix angle assuming a linear transmural variation in the helix angle. (c) Smooth rule-based systolic fiber field with epicardial and endocardial helix angles constrained to equal the angles determined from the in vivo helix angle maps. (d) Fiber field reconfigured from end-systole to a diastasis configuration using deformation gradient tensors obtained from tagged MRI.

Figure 3: Tag Tracked Kinematics animation. (a) Tracked points over the cardiac cycle obtained from neural-net based tagged MRI tracking algorithm (left). (b) Reference geometric tetrahedral model (obtained from cine bSSFP) nodal positions over the cardiac cycle interpolated from tracked points (right)

Figure 4: Mechanical Behavior in equibiaxial extension. Following a simulated equibiaxial test, the principal Cauchy stress vs stretch in the fiber and transverse (dashed lines) directions are shown for (a) the optimized cardiac material parameters obtained in this study (b) material parameters obtained in the study by Wang et al (c) material parameters from the study by Naspoulou et al.

Figure 5: Animation of computed LV deformation during simulated passive inflation. Short-axis slices show the spatial variation in displacement magnitude