4455

The Brain-Heart-Placenta Connection: Multimodal Investigation of Neurodevelopment in Mice with Congenital Heart Disease1Department of Developmental Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsbrugh, PA, United States, 2Rangos Research Center Animal Imaging Core, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 3Department of Developmental Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 4Department of Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 5Department of Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 6Department of Pediatrics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 7Biomedical Imaging Research Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Heart, Fetus, Congenital Heart Disease

Neurodevelopmental deficits (NDD) are a prevalent debilitating factor in patients with congenital heart disease (CHD) even after successful surgical palliation, but the etiology for NDD is not understood. Our study in a transgenic mouse model carrying causative genetic mutations found that NDD associated with CHD is not merely the consequence of compromised fetal hemodynamics, but primarily driven by intrinsic genetic factors and modulated by the placenta. Our study suggests that placental functions might potentially be a possible intervention strategy to overcome intrinsic genetic disadvantages.Introduction

Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) affects 1% of all live births in the United States. Neurodevelopmental deficits (NDD) are a prevalent debilitating factor in patients with congenital heart disease (CHD) even after successful surgical palliation. Impairments can include deficits in cognitive and motor performance, executive functioning, language and social cognition. As complexity of CHD increases, so does NDD severity [1-3], such as the association of microcephaly (MCPH) with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), a complex CHD involving hypoplasia of left-sided heart structures [4]. Here we investigated NDD associated with CHD using a previously characterized mouse model of HLHS, Ohia, in which recessive mutations in two genes were shown to cause HLHS and other CHD[5]. As observed in HLHS patients, CHD and NDD in this mutant mouse line showed variable phenotypic severity and with incomplete penetrance.While hemodynamic perturbations are often thought to underlie NDD associated with CHD, we propose a paradigm shift, hypothesizing the NDD associated with CHD in Ohia mutant mice have a common genetic etiology. Moreover, as placental function is critical in mediating oxygen and nutrient delivery required for proper development of the fetus, we further hypothesize the variable phenotype severity and penetrance of CHD/NDD may be related to placental function deficits.

Methods

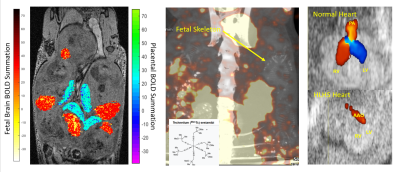

Animal Model: Ohia mutant mice heterozygous for recessive Pcdha9 and SAP130 mutations causing HLHS and other related CHD [5] were mated and the resulting embryos were analyzed with in utero imaging by ultrasound, MRI and SPECT, then harvested for genotyping and CHD phenotyping.Multimodal Imaging (Figure 1):

MRI: On days E14.5 and E16.5, volumetric and functional analysis of the fetal brain and placenta were measured by 4D time-and-motion-resolved fetal MRI. 4D-fMRI was acquired with FOV=4.5cm×3cm×2cm, isotropic voxel size 120μm×120μm×120μm, FA=10°, TE=4.5ms, TR=8.3ms, total scan time=40min. Using a hybrid, low rank, and sparse model, we are able to image with high spatiotemporal resolution in the same scan [6]. Individual brain and placenta BOLD signals and placenta oxy wavelet function were recorded in response to cyclic hypoxia challenges and correlation with genotypes and cardiac phenotypes was examined.

SPECT: Placental substrate delivery was evaluated by Tc99-sestimibi detected by SPECT.

Ultrasound: Cardiac structure/function were assessed by fetal ultrasound imaging.

Results

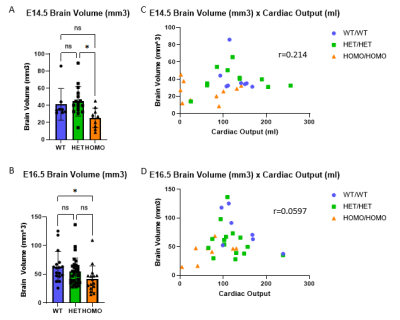

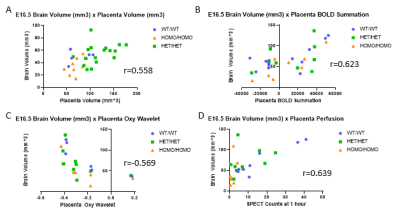

Multimodal imaging showed fetal brain volumes did not correlate with cardiac outputs (E14.5 r=0.214, E16.5 r=0.221), but instead were correlated with genotype, with small brain volumes associated with homozygous Sap130m/m Pchda9m/m mutant fetuses (Fig 2). Moreover, the multimodal imaging showed the fetal brain outcomes are highly correlated with placental volume, substrate delivery to the placenta, and placental capability to compensate for acute hypoxic challenges assessed by oxy wavelet function (Fig 3). Placental abnormality is also significantly correlated with reductions in head circumference and body weight.Conclusion

We showed in Ohia mutant mice, placental function plays a pivotal role in determining the penetrance and severity of cardiac and neurodevelopmental defects associated with the Sap130/Pcdha9 mutations. This was indicated with poor placental adaptation to hypoxia challenges, poor substrate delivery to the placenta and low placenta volume significantly correlating with mutant fetuses with smaller brains and poor cardiac output. These findings suggest possible strategy to improve clinical outcome in pregnancies with known genetic risks for CHD and NDD with prenatal intervention to support placental function for reducing disease severity or even possible disease prevention.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Brosig, C.L., et al., Neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 and 4 years in children with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis, 2018. 13(5): p. 700-705.

2. Naef, N., et al., Neurodevelopmental Profiles of Children with Congenital Heart Disease at School Age. J Pediatr, 2017. 188: p. 75-81.

3. Knirsch, W., et al., Structural cerebral abnormalities and neurodevelopmental status in single ventricle congenital heart disease before Fontan procedure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, 2017. 51(4): p. 740-746.

4. Marino, B.S., et al., Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Children With Congenital Heart Disease: Evaluation and Management. Circulation, 2012. 126(9): p. 1143-1172.

5. Liu X, Yagi H, Saeed S, et al. The complex genetics of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Nat Genet. 2017;49(7):1152-1159. doi:10.1038/ng.3870

6. Christodoulou, A.G., et al. Fetal Brain-Heart-Placental Interactions with Acute Hypoxia Challenge in Genetic Mouse Models of Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome with in utero 4D Dynamic MRI. in ISMRM International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2019. Montreal, QC, Canada.

Figures