4436

Application of Metabolic Imaging of Hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyruvate to a Genetic Mouse Model of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis

Aditya Jhajharia1, Salaheldeen Elsaid1, Minjie Zhu1, Joshua Rogers1, Youngshim Choi2, Liqing Yu2, Sui Seng Tee1, and Dirk Mayer1

1Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

1Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Liver, Hyperpolarized MR (Non-Gas), NASH

This study applied metabolic imaging of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate to a genetic mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Histology of the NASH (livKO) mice showed different levels of liver injury that were categorized into mild, moderate, and severe. NASH mice with severe liver injury had significantly higher Lac-to-Pyr and Ala-to-Pyr ratios in liver ROIs than that in control animals . These results suggest that hyperpolarized MRSI can be a promising method to differentiate liver injury based on severity in NASH. We also discussed several sources for variability of the MR data and how to potentially address them.Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease in the developed world with prevalence proportions of 20-46% in the United States.1 NAFLD can progress into a more severe form, called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which can cause the risk of liver cirrhosis, liver cancer, and liver failure. At present, liver biopsy is the most reliable method for diagnosis of NASH, however, this invasive technique suffers from sampling errors that can cause complications.2 Therefore, a noninvasive method to differentiate NASH from steatosis is an unmet clinical need.Hyperpolarized magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (hpMRSI) offers a unique advantage by providing real-time metabolic information in vivo under both normal and pathological conditions. It enhances 13C magnetic resonance (MR) signal by a factor of up to 5 orders of magnitude using dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization (dDNP). It provides a real-time assessment of pyruvate (Pyr) to lactate (Lac) and Pyr to alanine (Ala) conversion, which are potential biomarkers of inflammation and liver tissue alanine transaminase (ALT) activity, respectively.3 In this project, we aim to explore if hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyr MRSI can detect metabolic differences in a genetically engineered mouse model of NASH.

Materials and Methods

Mice lacking comparative gene identification 58 (CGI-58) can develop NASH.4 Liver CGI-58 knockout (LivKO) (n=10) and CGI-58-floxed mice (Control) (n=4) were fed a standard chow diet to the age of 6 months. After the imaging session animals were euthanized and liver tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for histology evaluation.A GE SPINlab polarizer operating at 5 T and 1.2 K was used to hyperpolarize [1-13C]pyruvate. A dose of 10 uL/g bw of hyperpolarized Pyr (~80 mM) was injected through a tail vein catheter into mice for imaging. A clinical 3 T GE 750w MRI scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) was used for in vivo MRSI. A 1H/13C volume coil (i.d. 50 mm) was used for both radiofrequency (RF) excitation and signal reception. A fast 3D spiral chemical shift imaging (spCSI)5 sequence with field of view (FOV)= 40×40×48 mm3 (2.5×2.5×4 mm3 resolution, 18 echoes, 280-Hz spectral width) was started at the time of injection with the repetition time (TR) of 12 s. A multiband RF pulse6 was used for the signal excitation, which applied different flip angles for each metabolite (2° on Pyr and 8° on both Lac and Ala). A total of seven-time points were acquired over 84 s. The time-averaged maps for Pyr, Lac, and Ala were generated by the integration of metabolite peaks in the absorption mode. Lac-to-Pyr and Ala-to-Pyr ratios were calculated in regions of interest (ROIs) manually drawn. One-tailed student’s unpaired t-test was done for statistical analysis.

Results and Discussion

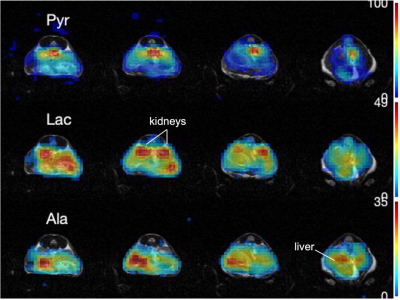

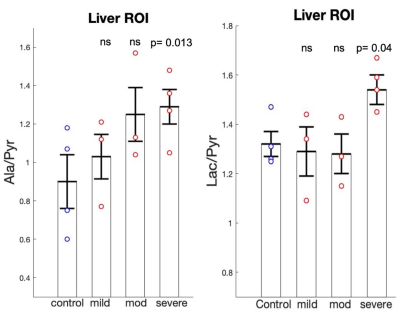

Figure 1 shows representative time averaged-metabolic maps of Pyr, Lac, and Ala in a NASH mouse. The histology evaluation of the control mice liver tissues showed normal histology with no or minimal background inflammation, and no necrosis or fibrosis. In contrast, NASH mice showed a wide range of inflammation, necrosis, and steatosis. Both micro-vesicular and macro-vesicular steatosis were observed compared to controls (Fig. 2). NASH mice were categorized into three stages (mild, moderate, and severe) according to the level of liver injury observed in histology. Mice having severe liver injury show significantly higher Pyr-to-Lac (p= 0.013) and Pyr-to-Ala (p= 0.04) conversion compared to controls (Fig. 3). The remaining mice with moderate and mild liver injury showed comparatively lower Lac-to-Pyr and Ala-to-Pyr ratios with respect to mice having severely damaged liver (Fig 3). However, neither ratio was significantly different from control mice.There are multiple sources that can introduce variability to the MR data in addition to measurement noise. We might be able to differentiate mild to moderate from control animals by regulating the potential sources of these variabilities. Our experiments were done with free-fed state. However, it has been shown that the label exchange between hyperpolarized 13C-Pyr and Ala in perfused mouse liver7 and rats in vivo8 is reduced in fasted versus non-fasted states. Therefore, controlling for the prandial state could reduce variability. The use of multiband pulse in hpMRSI is beneficial as it preserves Pyr magnetization by applying a small flip angle and products can benefit from larger flip angles to achieve higher SNR. However, B0 field inhomogeneity can lead to deviation from the nominal flip angle when a resonance is moved outside the respective passband. This would affect signal intensity and, hence, quantification. Under the large [1-13C]pyruvate bolus conditions, the formation of [1-13C]lactate is not only limited by lactate dehydrogenase activity and NADH availability but also the existing Lac pool size.9,10 Therefore, addition of unlabeled Lac in the dissolution buffer could be used to probe for such potential pool size limitations. Controlling for these sources of variability should improve metabolic quantification and could potentially aid in detecting metabolic differences in liver with less severe injury.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrate that MRSI of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate can detect the severe injury in the livKO mouse model of NASH and can be improved by monitoring various factors leading to variability. Therefore, the method shows potential as a noninvasive clinical tool to differentiate between NAFLD and NASH.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 DK106395, R21 CA213020, R21 CA202694, R21 NS096575.References

- 1. Lazo, M., Hernaez, R., Eberhardt, M.S., Bonekamp, S., Kamel, I., Guallar, E., Koteish, A., Brancati, F.L., and Clark, J.M., Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. American journal of epidemiology, 2013. 178(1): p. 38-45.

- Kleiner, D. and Brunt, E., Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Pathologic Patterns and Biopsy Evaluation in Clinical Research. Seminars in Liver Disease, 2012. 32(01): p. 003-013.

- Mackenzie, J.D., Yen, Y.-F., Mayer, D., Tropp, J.S., Hurd, R.E., and Spielman, D.M., Detection of Inflammatory Arthritis by Using Hyperpolarized 13C-Pyruvate with MR Imaging and Spectroscopy. Radiology, 2011. 259(2): p. 414-20.

- Guo, F., Ma, Y., Kadegowda, A.K.G., Betters, J.L., Xie, P., Liu, G., Liu, X., Miao, H., Ou, J., Su, X., Zheng, Z., Xue, B., Shi, H., and Yu, L., Deficiency of liver Comparative Gene Identification-58 causes steatohepatitis and fibrosis in mice. Journal of lipid research, 2013. 54(8): p. 2109-2120.

- Josan S, Spielman D, Yen YF, Hurd R, Pfefferbaum A, Mayer D. Fast volumetric imaging of ethanol metabolism in rat liver with hyperpolarized [1-(13) C]pyruvate. NMR Biomed. 2012; 25(8):993-9.

- Larson PE, Kerr AB, Chen AP, Lustig MS, Zierhut ML, Hu S, Cunningham CH, Pauly JM, Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB. Multiband excitation pulses for hyperpolarized 13C dynamic chemical-shift imaging. J Magn Reson. 2008 Sep;194(1):121-7.

- Merritt, M.E., Moreno, K.X., Harrison, C., Malloy, C., and Sherry, D., Probing In Vivo Liver Metabolism with Hyperpolarized Pyruvate. World Molecular Imaging Congress, Dublin, Ireland, 2012, P482., 2012.

- Hu, S., Chen, A.P., Zierhut, M.L., Bok, R., Yen, Y.F., Schroeder, M.A., Hurd, R.E., Nelson, S.J., Kurhanewicz, J., and Vigneron, D.B., In vivo carbon-13 dynamic MRS and MRSI of normal and fasted rat liver with hyperpolarized 13C-pyruvate. Mol Imaging Biol, 2009. 11(6): p. 399-407.

- Hurd, R. E., Spielman, D., Josan, S., Yen, Y. F., Pfefferbaum, A., & Mayer, D. (2013). Exchange-linked dissolution agents in dissolution-DNP (13)C metabolic imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 70(4), 936–942.

- Xu T, Mayer D, Gu M, Yen YF, Josan S, Tropp J, Pfefferbaum A, Hurd R, Spielman D. Quantification of in vivo metabolic kinetics of hyperpolarized pyruvate in rat kidneys using dynamic (13) C MRSI. NMR Biomed 2011;24:997–1005.

Figures

Dynamic 3D 13C spCSI time-averaged axial metabolic maps of Pyr, Lac, and Ala from 4 of 12 slices (in-plane resolution 2.5x2.5 mm2, slick thickness 4 mm) superimposed onto T2W 1H MRI.

Fig. 2: (a) A representative micrograph of the liver stained with H&E showing the central vein; arrows, and hepatic strands (arrowheads) of control mice. (b) LivKO mice show severe steatosis with ballooning (★) and multiple (micro-vesicular steatosis) (●). (c) the scoring of NASH among male mice compared to controls.

Average lactate-to-pyruvate (left), and alanine-to-pyruvate (right) ratios for control, NASH mice with mild, moderate, and severe injury (left to right) with standard errors and individual values (control, severe: N=4; mild, moderate: N=3). Lac/Pyr (p=0.014) and Ala/Pyr (0.04) ratios are significantly higher in NASH mice with severe injury compared to controls.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4436