4424

Retrospective Correction of Second-order Concomitant Fields in 3D Perfusion Imaging with a High-performance Gradient System1GE Global Research, Niskayuna, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Gradients, Arterial spin labelling, Concomitant Field Correction

Magnetic resonance imaging using 3D stack-of-spirals at 3T on a high-performance gradient system such as the MAGNUS can be subject to strong second-order concomitant magnetic fields (SOCG), which can lead to signal dropout and blurring artifacts that become more significant at locations that are farther from the gradient isocenter. SOCG cannot be corrected by pre-emphasis of gradient waveforms and/or radio frequency modulation alone, and hence requires higher-order hardware or software solution. We demonstrate a software-based correction of SOCG in 3D pseudo-continuous arterial spin labelling with a stack-of-spirals k-space trajectory by nulling the phase contributed by SOCG during reconstruction.Introduction

Fast spin echo (FSE) with 3D stack-of-spirals (SOS) k-space encoding is often used for the readout of a 3D pseudo-continuous arterial spin-labeling (3DpCASL) pulse sequence. High-performance gradient systems, such as the MAGNUS, that can simultaneously achieve a strong gradient amplitude (Gmax) of 200 mT/m and a maximum slew rate (SRmax) of 500 T/m/s on each axis from a standard 620A/1400 V gradient driver have been used for rapid and high-quality 3DpCASL acquisitions at 3 T1,2. However, the utilization of higher Gmax, at a main magnetic field strength of 3T, is accompanied by stronger second-order concomitant gradient (SOCG) fields that cannot be corrected by pre-emphasis of gradient waveforms and/or radio frequency modulation alone3,4. Such SOCG can lead to signal dropout as well as in-plane and through-plane blurring (that increase with off-center distance) in 3DpCASL acquisitions. Here we retrospectively correct SOCG-induced erroneous phase in 3DpCASL by slice-dependent k-space phase compensation based on calculated SOCG in spiral readout. Successful correction is demonstrated in proton density (PD) and perfusion-weighted (PW) images of a phantom and a volunteer respectively.Materials and Methods

The acquired 3DpCASL raw signal $$$(S)$$$ that is corrupted by phase due to SOCG ($$$\phi_{c_2}$$$) is given as$$

\tag{1}

{S(k_x,k_y,k_z)= \iiint\rho(x,y,z)e^{-i(k_xx+k_yy+k_zz)e^{-i\phi_{c_2}}}dxdydz}

$$

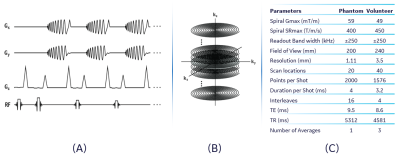

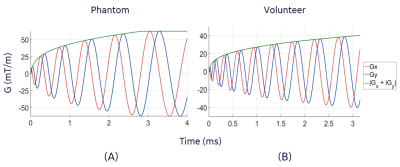

where $$$\rho(x,y,z)$$$ is the uncorrupted image, and we have ignored resonance relaxation effects. Considering that the k-space of our 3DpCASL was encoded using a 3D SOS with phase encoding in the $$$k_z$$$ direction (Figure 1), the dominant contribution to SOCG comes from the $$$x$$$ and $$$y$$$ gradients $$$(G_x$$$ and $$$G_y)$$$ during the readout interval. Hence $$$\phi_{c_2}$$$ is given by Bernstein et al as5:

$$

{\phi_{c_2}(z)=\frac{\gamma z^2 }{2B_0}\cdot \int_0^t\left(G_x^2(t')+G_y^2(t')\right)dt'}

\tag{2}

$$

To correct for $$$\phi_{c_2}$$$, we took an initial inverse z-transform of $$$S$$$ (by multiplying Equation (1) with $$$e^{-ik_zz'}$$$ and integrated over $$$k_z$$$) to obtain:

$$

{S'(k_x,k_y,z')=\iint\rho(x,y,z')e^{-(k_xx+k_yy)e^{-i\phi_{c_2}(z'^2)}}dxdy}

\tag{3}

$$

$$$S'$$$ was corrected by nulling $$$\phi_{c_2}$$$ on each slice (or $$$z'$$$) location before re-gridding to a cartesian coordinate system. A 2D inverse Fourier transform (in the $$$x$$$ and $$$y$$$ directions) of the re-gridded data was then used to obtain the corrected images, $$$\rho(x,y,z')$$$ at each slice location.

MRI Experiments: All 3DpCASL experiments were carried out on a MAGNUS gradient system with firmware patches for zeroth- and first-order eddy current and concomitant fields correction6,7. The Gmax, SRmax, and receiver bandwidth (rBW) of the spirals satisfied the azimuthal Nyquist criterion that is required to prevent k-space undersampling8. The labeling delay and post labeling delay for the acquisitions were set to 1450 ms and 1525 ms respectively. Acquired raw k-space data were processed for image reconstruction with and without SOCG correction. Image reconstruction was carried out in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) using the Orchestra software development kit (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisconsin, USA).

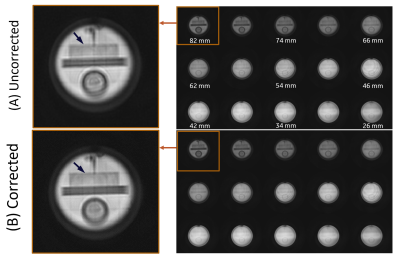

Phantom and Volunteer Acquisition: Phantom experiments were carried out using a 10 cm-diameter American College of Radiology MRI quality control phantom. The phantom was axially placed at 8 cm from the isocenter of the MAGNUS gradient and PD images were acquired using the 3DpCASL pulse sequence. Acquisition rBW and field of view (FOV) were 500 kHz and 20 mm respectively. The Gmax and SRmax of the spiral-out waveform design, and other details of the phantom experiment are shown in Figure 2C. A single volunteer (age 49, male) was imaged under IRB approved protocol after a written informed consent was received. PD and PW images were obtained using the 3DpCASL pulse sequence with rBW and FOV of 500 kHz and 24 mm respectively. Acquisition Gmax, SRmax and other details of the volunteer experiment are shown in Figure 2C. Cerebral blood flow (CBF) was calculated using the PW and PD images as previously described in the ASL consensus9.

Results and Discussions

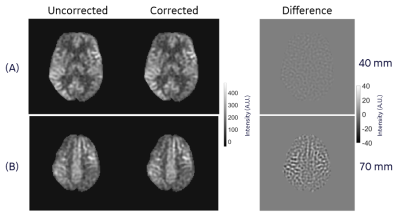

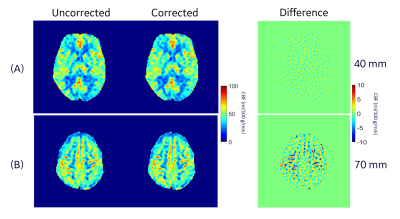

Results of our phantom acquisition showed that there is visible reduction of in-plane blurring (at slice location of 82 mm) in the corrected 3DpCASL images compared to the uncorrected reconstruction (Figure 4). Some gradient non-linearity artifacts are visible in the phantom images since we are close to the edge of spherical volume of the MAGNUS. In in vivo scans, there were differences of up to 10% (especially around the white and gray matter interfaces) at 70 mm from the gradient isocenter between the corrected and uncorrected 3DpCASL PW images (Figure 4) and CBF estimations (Figure 5). In this work, we demonstrated the effect of SOCG correction in 3DpCASL acquisitions with a spiral-out readout, as spiral k-space encoding has a low tolerance for such phase errors. The SOCG correction method described here is retrospective and does not require any additional pulse programming or compromise in imaging performance. The current method may also be combined with hardware correction methods to remove any residual SOCG phase after image acquisition. As a future work, this correction method can be extended for nulling the SOCG phase accrued in a full 3D spiral acquisition (without any Cartesian phase encoding) on a pixel-by-pixel basis. Since the computation time of such pixel-by-pixel correction may be excessive, a volumetric-patch-based correction may be considered for faster reconstruction.Conclusion

A retrospective SOCG correction method has been implemented for the correction of erroneous phase accruals due to SOCG in 3DpCASL acquisitions in the MAGNUS high performance gradient system.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by CDMRP W81XWH-16-2-0054. This presentation does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency. We also thank H. Doug Morris for the help rendered during our data gathering.References

1. Foo, T. K. F. et al. Highly efficient head-only magnetic field insert gradient coil for achieving simultaneous high gradient amplitude and slew rate at 3.0T (MAGNUS) for brain microstructure imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 83, 2356–2369 (2020).

2. Ajala, A. et al. 3D Pseudo-Continuous Arterial Spin Labeling Acquisition using a High-Performance Gradient System: A Scan Time and Image Quality Assessment. in ISMRM 2022 Annual Proceedings (2022).

3. Tao, S. et al. Gradient Pre-Emphasis to Counteract First-Order Concomitant Fields on Asymmetric MRI Gradient Systems. Magn Reson Med 77, 2250–2262 (2017).

4. Weavers, P. T. et al. B0 concomitant field compensation for MRI systems employing asymmetric transverse gradient coils. Magn Reson Med 79, 1538–1544 (2018).

5. Bernstein, M. A., King, K. F. & Zhou, X. J. Handbook of MRI Pulse Sequences. (Elsevier Academic Press, 2004).

6. Tao, S. et al. The Effect of Concomitant Fields in Fast Spin Echo Acquisition on Asymmetric MRI Gradient Systems. Magn Reson Med 79, 1354–1364 (2018).

7. TAO, S., TRZASKO, J. D., Shu, Y., WEAVERS, P. T. & BERNSTEIN, M. A. Systems and methods for concomitant field correction in magnetic resonance imaging with asymmetric gradients. (2016).

8. Kang, D. et al. The effect of spiral trajectory correction on pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling with high-performance gradients on a compact 3T scanner. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 84, 192–205 (2020).

9. Alsop, D. C. et al. Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: A consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the European consortium for ASL in dementia. Magn Reson Med 73, 102–116 (2015).

Figures