4390

Development and Evaluation of an MR-visible Interventional Microcatheter1Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Interventional Devices, Interventional Devices

Intra-arterial chemotherapy following blood-brain barrier opening (BBBO) can be a highly effective therapeutic delivery mechanism when treating primary and metastatic disease in the brain. Osmotic blood-brain barrier disruption has long been performed under x-ray guidance but has yet to gain clinical traction partially due to outcome variability. MRI is advantageous for its superior soft tissue contrast and real-time perfusion territory validation. We propose a passive microcatheter to provide real-time feedback of catheter positioning during BBBO under MRI guidance. In a phantom, we quantitated susceptibility artifacts at 3T. The catheter showed promise as a new MRI-visible tool to enhance BBBO procedures.Introduction

Intraarterial chemotherapy (IAC) administration has been found to increase drug concentration delivery to tumors and the surrounding brain tissue with reduced systemic toxicity, in comparison to traditional intravenous infusion when treating primary and metastatic disease in the brain1. Efficacy of intraarterial agents is further enhanced via blood-brain barrier opening (BBBO), permitting delivery of ionized water-soluble agents and those of molecular weights larger than 180 Da2,3. Osmotic blood-brain barrier opening (OBBBO) was introduced over 4 decades ago, but has yet to gain clinical traction3. Such procedures are guided using x-ray digital subtraction angiography (DSA), giving rise to high procedural variability in treatment of disease that calls for utmost soft tissue contrast and multiparametric tissue characterization. As a result, current research has focused on dynamic contrast susceptibility (DSC) MRI for real-time validation of blood-brain barrier permeability, tumor margin delineation, and understanding of catheter perfusion territory4,5. Catheter position is directly related to perfusion territory, thus understanding tip position in real-time is paramount. Currently, there are no MR-visible microcatheters available on the market, and those currently in use, while MR-compatible, are MR-translucent. To better understand the positioning of a catheter during real-time MRI guidance and increase procedural efficacy, we propose a passive microcatheter and evaluate its susceptibility artifacts in vitro.Methods

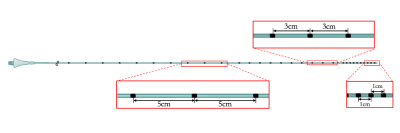

Catheter constructionAn MRI-compatible, 1.2 Fr flow-directed microcatheter (Magic, Balt, Montmorency, France) was used as the base device in this study, per prior studies4. Passive markers were made from an epoxy-based radiopaque ink (Creative Materials, Ayer, MA) doped with iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles (IONPs) of 20-40 nm diameter (Alfa Aesar, Tewksbury, MA). The ink was comprised of tungsten or tantalum at 80% or higher (by weight)6. IONPs were incorporated into the ink at 0.5 wt% (w/w) for markers in this study. Starting 1 cm from the distal tip, 10 circumferential markers were applied 1-cm apart in series, followed by 10 markers 3-cm apart and another 10 markers that were 5-cm apart down the catheter length (FIG.1). Markers were allowed to cure at 20ºC overnight.

In vitro susceptibility artifact quantitation

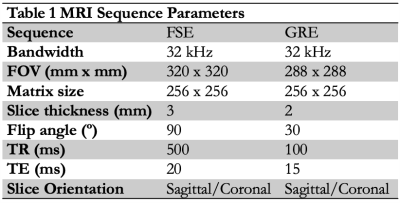

Local areas around the passive marker bands will appear as negative contrast under MRI, due to B0 field inhomogeneities resulting in dephasing of adjacent proton spins and a local signal void or susceptibility artifact7,8. Artifacts were measured per ASTM F2119-07 in a 10% (w/v) poly(vinyl) alcohol cryogel (PVA-C) vascular phantom with MR relaxation times similar to body tissues9. Catheters were inserted in the phantom and oriented parallel to B0 in a. The phantom was filled, and catheters flushed, with copper sulfate phantom (CuSO4, 1-2 g/L) to reduce T1 relaxation times and avoid background signal saturation. Images were acquired on a 3T MRI scanner (Discovery MR 750w, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). A gradient echo (GRE) and T2-weighted fast spin echo (FSE) were acquired (Table 1). For each image slice orientation, maximum artifact width was evaluated from all slices, using ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij).

Results

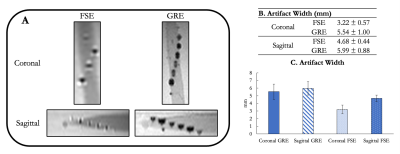

In vitro susceptibility artifact quantitationNegative contrast signal induced by the IONP-doped ink was demonstrated by the passive markers at 3.0T (FIG. 2A). Each marker was distinct, without overlapping. The distal-most 10 markers separated by 1-cm were able to be visualized, while all others remained out of the field of view. Largest susceptibility artifacts were observed on the GRE – with 5.54 mm and 5.99 mm in coronal and sagittal orientations, respectively (FIGS. 2b and 2C).

Discussion and Conclusions

Imaging under MRI demonstrated a microcatheter with negative contrast at 3T in vitro. A device with these characteristics could enable real-time intra-procedural validation of OBBBO procedures, increasing treatment efficacy and procedural efficiency. Current procedures check tip position of the microcatheter by infusion of Feraheme MRI contrast agent – with passive markers, tip position could be appreciated in real-time, potentially reducing procedure time. It has been noted in prior literature that even the most minute changes in catheter tip position can result in differential perfusion of brain territory, thus the ability to see the tip through OBBBO procedures under MRI guidance is paramount. The susceptibility artifacts evaluated in this study could enable navigation into small intracranial vessels, but further composition optimization and testing will be required. It is possible to further customize marker composition to ensure that susceptibility artifact does not impact territory identified on DSC MRI, but this would be best suited for in vivo studies in the future. Finally, while we do not anticipate MR safety to be an issue, it should be thoroughly quantitated through evaluation of the RF-induced heating and magnetically induced torque in the MRI environment, per ASTM F2182 and F2213-17, respectively.Acknowledgements

Dan Scdoris and Mike DeGuzman for their help with imaging studies. Eugene Ozhinsky and Kisoo Kim for their help with real-time navigation. This project was supported by National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health, through S. Hetts Grant Numbers R01 EB012031 and R21 EB020283. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policies of the NIH.References

1. Doolittle, N. D. et al. Safety and efficacy of a multicenter study using intraarterial chemotherapy in conjunction with osmotic opening of the blood-brain barrier for the treatment of patients with malignant brain tumors. Cancer 88, 637–647 (2000).

2. KrolI, R. A., Neuwelt, E. A. & Neuwelt, E. A. Outwitting the Blood-Brain Barrier for Therapeutic Purposes: Osmotic Opening and Other Means. Neurosurgery 42, 1083–1099 (1998).

3. Janowski, M., Walczak, P. & Pearl, M. S. Predicting and optimizing the territory of blood–brain barrier opening by superselective intra-arterial cerebral infusion under dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI guidance. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 36, 569–575 (2016).

4. Zawadzki, M. et al. Real-time MRI guidance for intra-arterial drug delivery in a patient with a brain tumor: technical note. BMJ Case Rep. 12, bcr-2018-014469 (2019).

5. Zawadzki, M. et al. Follow-up of intra-arterial delivery of bevacizumab for treatment of butterfly glioblastoma in patient with first-in-human, real-time MRI-guided intra-arterial neurointervention. J. Neurointerventional Surg. 13, 1037–1039 (2021).

6. Medical Coatings and Deposition Technologies. Medical Coatings and Deposition Technologies (2016). doi:10.1002/9781119308713.

7. Glowinski, A. et al. Device visualization for interventional MRI using local magnetic fields: Basic theory and its application to catheter visualization. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging (1998) doi:10.1109/42.736037.

8. Omary, R. A. et al. Real-time MR imaging-guided passive catheter tracking with use of gadolinium-filled catheters. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. (2000) doi:10.1016/S1051-0443(07)61343-8.

9. Surry, K. J. M., Austin, H. J. B., Fenster, A. & Peters, T. M. Poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogel phantoms for use in ultrasound and MR imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 49, 5529–5546 (2004).

10. Jiang, Y. Y. et al. In Vitro Quantification of the Radiopacity of Onyx during Embolization. Neurointervention (2017) doi:10.5469/neuroint.2017.12.1.3.

Figures