4382

Dephased bSSFP for the Delineation of Interventional Devices

Jonas Frederik Faust1,2, Peter Speier1, Axel Joachim Krafft1, Sunil Patil3, Mark E. Ladd2,4, and Florian Maier1

1Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 2Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany, 3Siemens Medical Solutions USA Inc., Malvern, PA, United States, 4German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany

1Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 2Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany, 3Siemens Medical Solutions USA Inc., Malvern, PA, United States, 4German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Interventional Devices, MR-Guided Interventions

Dephased MRI, e.g., used for the delineation of metallic interventional devices, is the reconstruction of images from a shifted k-space and can be achieved by introducing additional “White-Marker” magnetic field gradient moments into the acquisition scheme. A prototype 3D radial sequence was implemented to analyze and compare the artifact of a biopsy needle in a gel phantom for dephased GRE and dephased bSSFP contrast. We found dephased bSSFP to show improved artifact symmetry in comparison with dephased GRE. Undesired signal attributed to fat tissue interfaces in an ex-vivo phantom was successfully suppressed by introducing an altered bSSFP phase cycling.Introduction

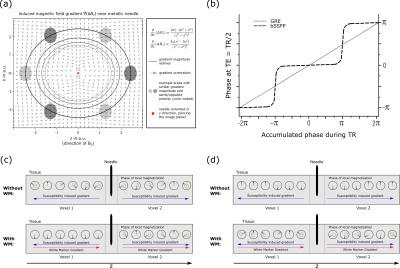

In interventional MRI, accurate and unambiguous localization of interventional devices is desirable.1,2 Metallic devices, such as biopsy needles, cause a characteristic artifact3 in MR images as they induce local magnetic field gradients4 (Fig. 1a) that will lead to a signal loss near the device due to dephasing of the local magnetization in Gradient Recalled Echo (GRE) imaging. While the negative contrast can be used for localization, low signal areas in MR images can also be caused by other effects which might hamper device identification. Therefore, susceptibility-based positive contrast methods for the delineation of interventional devices were developed.5-14 A popular approach is dephased MRI13. So-called White-Marker (WM)6 gradients partially counteract dephasing induced by the metallic device, generating a contrast characterized by signal-intense areas near the device and dark dephased background.WM gradients can be introduced into GRE sequences, but not into spin-echo sequences, as the 180° pulse would revert the introduced dephasing. A combination of Balanced Steady State Free Precession (bSSFP)15 imaging with WM has been used for the delineation of interventional devices16,17, and signal enhancement has been found to be higher with d-bSSFP (dephased bSSFP) than with d-GRE (dephased GRE)18. As the categorization of bSSFP as a spin or gradient echo sequence has been debated19, signal formation in d-bSSFP was investigated in this work. In bSSFP, magnetization refocuses at TE=TR/2 either with 0° or 180° phase depending on the off-resonance of the local proton resonance frequency (Fig. 1b).15 This leads to a discontinuous dephasing pattern near a metallic device that is independent of the polarity of the local gradient (Fig. 1d), unlike in d-GRE where the dephasing pattern is continuous (Fig. 1c). Consequently, a WM gradient in d-bSSFP can induce a rephasing effect independent of its polarity and therefore recover additional signal (Fig. 1a) which yields a higher artifact symmetry as would be seen with d-GRE.

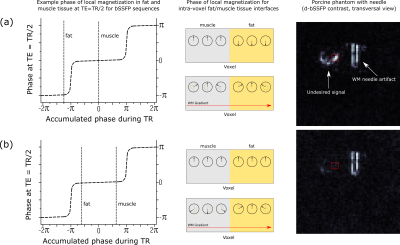

While the WM gradients can fully suppress signal in homogeneous tissue, signal intensities which are not attributed to a metallic perturber can arise in the WM image for heterogeneous tissue, e.g., due to partial volume effects.20 We hypothesize that part of these signal intensities can also be linked to a chemical shift-related effect at fat tissue interfaces. The difference in resonance frequency between fat and, e.g., muscle tissue can cause dephasing across the tissue interface, depending on TR, which can in turn be rephased by the WM gradient (Fig. 5). We expect this effect to generate undesired signal in d-GRE and d-bSSFP. In this work, we propose an adapted phase cycling scheme for d-bSSFP to suppress the undesired signal.

Methods

A prototype 3D radial21 sequence22,23 was implemented on a 1.5T system (MAGNETOM Sola, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Radial acquisition with varying frequency encoding direction was chosen to counteract spatial misregistration of the artifact due to the altered resonance frequency near metallic devices.12 RF-spoiled24,25 d-GRE (Fig 2b) and d-bSSFP (Fig 2c) were implemented and the generated WM contrast was studied for an MR-compatible biopsy needle (KIM16/14, ITP GmbH, Bochum, Germany) in a gel and an ex-vivo porcine phantom (Fig. 3) using a 20-channel head coil (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). To suppress undesired signal resulting from WM rephasing of magnetization across fat tissue interfaces, the standard phase cycling scheme for bSSFP sequences (180° phase advance per TR) is altered by changing the phase increment ϕ for each RF pulse:$$\phi = 180°-\frac{\text{CS}_{\text{fat,water}}\times\text{PRF}_{\text{water}}}{2}\times\text{TR}\times360°$$Here, CSfat,water describes the chemical shift between fat and water and PRFwater is the proton resonance frequency of water, to which the transmitter/receiver frequency is adjusted. The altered phase cycling scheme enforces the fat and water resonances to be placed symmetrically in the bSSFP band structure16 (Fig. 5) and therefore the magnetization to refocus with the same phase at the echo time (TE). Consequently, a WM gradient will now only have a dephasing effect across the fat tissue interface and suppress the signal.Results

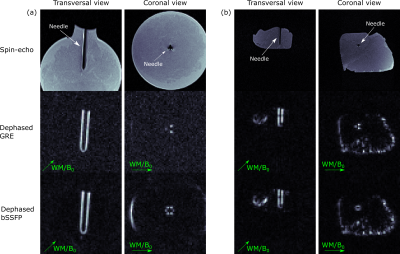

In Fig. 4, images of the investigated phantoms are shown which were acquired with the d-GRE and the d-bSSFP sequence. A more symmetric artifact pattern is seen for the d-bSSFP compared to the d-GRE sequence. Undesired signal which is attributed to fat tissue interfaces could be reduced for d-bSSFP using the adapted phase cycling scheme (Fig. 5). A signal reduction of 80% was measured in a Region-of-Interest (ROI) which encompasses the observed undesired artifact.Discussion

The improved artefact symmetry for d-bSSFP compared to d-GRE might allow for a more accurate localization of the needle as the device's location coincides with the artefact's center of mass. With the introduction of an altered RF phase cycling scheme, undesired signal attributed to fat tissue interfaces could be suppressed, potentially allowing for a more robust device identification. The proposed phase cycling allows for full flexibility in choosing TR, as magnetization in fat and adjacent tissue are always refocused with the same phase. Potential adverse effects of field inhomogeneities on the effectiveness of the introduced tissue interface signal suppression, e.g., due to imperfect shimming, must be considered in future investigations.Conclusion

Compared to d-GRE, d-bSSFP showed improved artifact symmetry and allowed for suppression of undesired signal attributed to fat tissue interfaces. This potentially enables more robust and more accurate device localization.Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Heinz-Werner Henke (Innovative Tomography Products GmbH, Bochum, Germany) for providing the MR-compatible needle.References

- Weiss CR, Nour SG and Lewin JS. MR-guided biopsy: A review of current techniques and applications. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008;27:311-325.

- Lederman RJ. Cardiovascular Interventional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Circulation 2005;112:3009–3017.

- DiMaio SP, Kacher DF, Ellis RE et al. Needle artifact localization in 3T MR images. Stud Health Technol Inform 2006;119:120-125.

-

Ladd ME, Erhart P, Debatin JF et al.

Biopsy needle susceptibility artifacts. Magn Reson Med 1996;36:646–651.

- Vonken E-JP, Schär M, Yu J, Bakker CJ and Stuber M. Direct in vitro comparison of six three-dimensional positive contrast methods for susceptibility marker imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013;38:344–357.

- Seppenwoolde JH, Viergever MA, Bakker CJ. Passive tracking exploiting local signal conservation: the white marker phenomenon. Magn Reson Med 2003;50(4):784–790.

- Dharmakumar R, Koktzoglou I and Li D. Generating positive contrast from off-resonant spins with steady-state free precession magnetic resonance imaging: theory and proof-of-principle experiments. Phys Med Biol 2006;51(17):4201–4215.

- Koktzoglou I, Li D and Dharmakumar R. Dephased FLAPS for improved visualization of susceptibility-shifted passive devices for real-time interventional MRI. Phys Med Biol 2007;52(13):277–286.

- Çukur T, Yamada M, Overall WR, Yang P and Nishimura DG. Positive contrast with alternating repetition time SSFP (PARTS): A fast imaging technique for SPIO-labeled cells. Magn Reson Med 2010;63:427–437.

- Stuber M, Gilson WD, Schär M, et al. Positive contrast visualization of iron oxide-labeled stem cells using inversion-recovery with ON-resonant water suppression (IRON). Magn Reson Med 2007;58:1072–1077.

- Dahnke H, Liu W, Herzka D, Frank JA and Schaeffter T. Susceptibility gradient mapping (SGM): a new postprocessing method for positive contrast generation applied to superparamagnetic iron oxide particle (SPIO)-labeled cells. Magn Reson Med 2008;60:595–603.

- Seevinck PR, de Leeuw H, Bos C and Bakker CJG. Highly localized positive contrast of small paramagnetic objects using 3D center-out radial sampling with off-resonance reception. Magn Reson Med 2011;65:146–156.

- Patil S, Bieri O and Scheffler K. Echo-dephased steady state free precession. Magn Reson Mater Phy 2009;22:277–285.

- Bakker CJ, Seppenwoolde JH and Vincken KL. Dephased MRI. Magn Reson Med 2006;55: 92-97.

- Bieri O. and Scheffler K. Fundamentals of balanced steady state free precession MRI. J. Magn Reson Imaging 2013;38:2–11.

- Weine J, Schneider R, Kägebein U et al. Interleaved White Marker Contrast with bSSFP Real-Time Imaging for Deep Learning based Needle Localization in MR-Guided Percutaneous Interventions. ISMRM 27th Annual Meeting & Exhibition 2019.

- Campbell-Washburn AE, Rogers T, Xue H et al. Dual echo positive contrast bSSFP for real-time visualization of passive devices during magnetic resonance guided cardiovascular catheterization. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2014;16:88.

- Reiß S, Krafft AJ, Düring K et al. To Spoil or To Balance? A Comparison of the White Marker Phenomenon in Gradient Echo Pulse Sequences. ISMRM 23rd Annual Meeting & Exhibition 2015.

- Scheffler K and Hennig J. Is TrueFISP a gradient-echo or a spin-echo sequence? Magn Reson Med 2003;49:395–397.

- Seppenwoolde JH, Vincken KL and Bakker CJ. White-marker imaging—Separating magnetic susceptibility effects from partial volume effects. Magn Reson Med 2007;58:605–609.

- Chan RW, Ramsay EA, Cunningham CH and Plewes DB. Temporal stability of adaptive 3D radial MRI using multidimensional golden means. Magn Reson Med 2009;61:354–363.

- Faust JF, Krafft AJ, Polak D et al. Fast 3D Passive Needle Localization for MR-Guided Interventions using Radial White Marker Acquisitions and CNN Postprocessing. In: Proceedings of the 30th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, London, United Kingdom, 2022. p 1196.

- Faust JF, Polak D, Ladd ME and Maier F. Improving Accuracy of White Marker Contrast-Based Rapid 3D Passive MR Biopsy Needle Localization by Utilizing a Total Variation-Regularized Image Reconstruction. In: Proceedings of the 14th Interventional MRI Symposium, Leipzig, Germany, 2022. p 97.

- Zur Y, Wood ML, Neuringer LJ. Spoiling of transverse magnetization in steady state sequences. Magn Reson Med 1991;21:251–263.

- Leupold J, Hennig J and Scheffler K. Moment and direction of the spoiler gradient for effective artifact suppression in RF-spoiled gradient echo imaging. Magn Reson Med 2008;60:119–127.

Figures

Figure 1: (a) A local magnetic field

gradient is introduced by a needle.4 Various areas are subjected to

the same gradient magnitude with same/opposite polarity. (b) Near the needle,

local magnetization will experience a continuous/discrete19 dephasing

at TE for GRE/bSSFP due to the induced gradient. For GRE (a), a WM gradient can

rephase magnetization if it has opposite polarity, for bSSFP (d) the WM

gradient can also (partially) rephase magnetization if it has the same polarity

as the local gradient.

Figure 2: (a) 3D radial acquisition.21-23 WM gradient moments6 (causing a 2π shift of acquired k-space

in z-direction) are added (red) to an RF-spoiled GRE (b) and a bSSFP (c)

sequence. For d-GRE, all gradients are rewound except a spoiler gradient played

out orthogonal to the WM gradient. For the d-bSSFP sequence, all gradient

moments are rewound and the RF phase is cycled with an increment of ϕ = 180° by default.

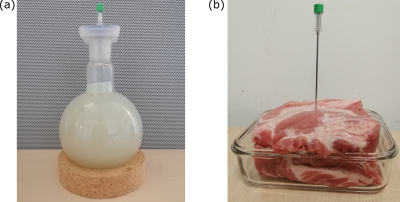

Figure 3: A gel phantom (a) and an

ex-vivo porcine phantom similar to (b), including a biopsy needle, were used to

investigate dephased MRI contrast. Scan parameters for gel phantom: TE=2.20ms;

TR=4.40ms; bandwidth=900Hz; FOV=(128mm)3; image matrix=(64px)3.

Scan parameters for ex-vivo phantom: TE=1.72ms; TR=3.44ms; bandwidth=900Hz;

FOV=(256mm)3; image matrix=(64px)3. Flip angle (d-GRE)=5°;

flip angle (d-bSSFP)=70°. Spin-echo reference scan: TR=233ms; TE=73ms; FOV=(256mm)3;

image matrix=(256px)3.

Figure 4: MR images of the

investigated gel phantom (a) and the ex-vivo porcine phantom (b). The first row

shows a spin-echo image as a reference, the second and third row show the d-GRE

and d-bSSFP (180° phase cycling) contrast. Green arrows indicate the WM

gradient direction (parallel to B0). The needle artifact as seen in the coronal slice shows an

additional symmetry for d-bSSFP compared to d-GRE as also areas with opposite

local gradient polarity are rephased by the WM gradient (compare Fig. 1a).

Figure 5: (a) At fat tissue interfaces, the magnetization can accumulate different phases due to chemical

shift. A WM gradient can partially refocus the magnetization at the interface, eliciting

undesired signal. (b) Introducing an additional phase advance between consecutive

TRs for the d-bSSFP sequence will cause magnetization to refocus with the same

phase at TE=TR/2, and the WM will have a dephasing effect across the tissue

interface, suppressing the undesired signal (by 80% for red ROI).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4382