4355

Amniotic Fluid Segmentation using Convolutional Neural Networks

Alejo Costanzo1,2, Birgit Ertl-Wagner3,4, and Dafna Sussman1,5,6

1Department of Electrical, Computer and Biomedical Engineering, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Institute for Biomedical Engineering, Science and Technology, Toronto Metropolitan University and St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Division of Neuroradiology, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4Department of Medical Imaging, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 5Institute for Biomedical Engineering, Science and Technology, Toronto Metropolitan University and St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

1Department of Electrical, Computer and Biomedical Engineering, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Institute for Biomedical Engineering, Science and Technology, Toronto Metropolitan University and St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3Division of Neuroradiology, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4Department of Medical Imaging, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 5Institute for Biomedical Engineering, Science and Technology, Toronto Metropolitan University and St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Segmentation, Convolutional Neural Network

Amniotic Fluid Volume (AFV) is an important fetal biomarker when diagnosing certain fetal abnormalities. We aim to implement a novel Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model for amniotic fluid (AF) segmentation which can facilitate clinical AFV evaluation. The model, called AFNet was trained and tested on a radiologist–validated AF dataset. AFNet improves upon ResUNet++ through the efficient feature mapping in the attention block, and transpose convolutions in the decoder. Experimental results show that our AFNet model achieved a 93.38% mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) on our dataset. We further demonstrate that AFNet outperforms state-of-the-art models while maintaining a low model size.Introduction

A key essential fluid needed for fetal development is amniotic fluid1–3. Non-invasive estimation techniques are commonly used for the challenging quantification of amniotic fluid volume4–7. The use of fetal MRIs provides high contrast and spatial resolution to visualize the entire AFV in one sequence acquisition; this provides another form of quantifying AFV other than using US estimation. Manual segmentation of AF on MRI sequences is quite cumbersome, time-consuming, and not feasible in the clinical routine assessment. A solution is to use machine learning techniques that are similar to the accuracy of an expert8–10. Deep learning is an established field within machine learning that uses algorithms such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) as a specialized tool in medical imaging tasks11–19. For MRI datasets based on the fetal brain, placenta, and body, previous studies20–22, have shown strong model performance. Literature on the application of deep learning models for the segmentation of amniotic fluid specifically for MRI is currently lacking. This study aims to create an expert-validated MR dataset with segmented amniotic fluid and implement an improved state-of-the-art network to segment AF.Methods

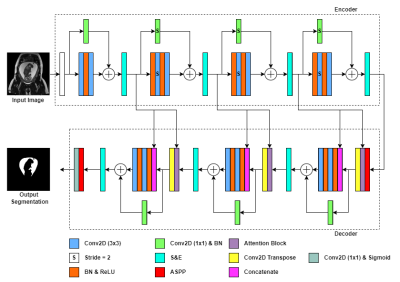

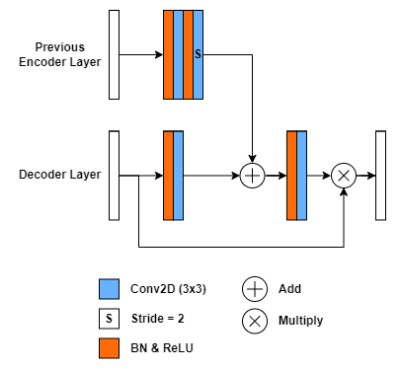

The dataset used for this study consists of 45 T2-weighted 3D fetal MRI sequences obtained using an SSFP sequence on a 1.5T or a 3.0T MR scanner. For each 3D patient MRI about 50-120 reformatted sagittal slices were obtained. The input to the model would hence consist of 2D slices to be automatically segmented and reconstructed to a 3D set for each patient. Our ground truth label was manually performed in-house with the aid of the segmentation software Amira-Avizo (Berlin, Germany), then verified by an expert radiologist. Figure 1, demonstrates the implemented model, AFNet, which is an improved version of the original ResUNet++13, by replacing the upsampling layers with transposed convolutional layers and refining the attention block. Attention mechanisms serve to improve the feature maps of certain areas in the network, by which we applied a modified feature map connection from previous layers (Figure 2). We changed the encoder attention path of the attention block from a max pooling layer to an atrous convolution block of stride 2. This facilitates the attention mechanism to produce more efficient and representative encoder feature maps. From the total dataset of 3484 images, we split 55/15/20 percent of it to train, validation, and test sets, respectively. Afterwards, the dataset was randomly shuffled. The training set was normalized and to improve image diversity, data augmentation was performed. For hyperparameter optimization, we applied the Adagrad optimizer which allowed for faster model optimization. The model was trained for a maximum of 200 epochs with early stopping callbacks and a batch size of 8. The dice loss function was chosen for its robustness in training networks to recognize similarities in the ground truth. The main metrics for semantic segmentation used for the validation of our models were the Dice Coefficient and the mean Intersection over Union23.Results

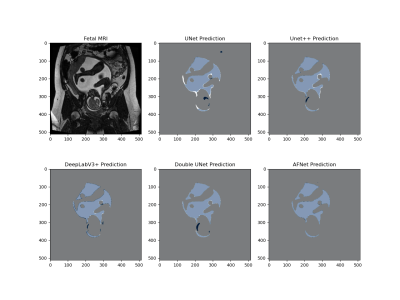

To validate the performance of the AFNet, we compared the mean IoU of our modified models with the original ResUNet++ with a paired student’s t-test. Figure 3 shows the results of our model modifications, where our attention module (AFNet noT) improved the original ResUNet++ by 1% on average (p = 0.043). In addition, the transposed convolution model with attention (AFNet) added about an extra 1% (p = 0.031) to performance. Figure 4 demonstrates the AFNet performance to state-of-the-art medical segmentation models. AFNet outperformed the U-Net, DeepLabV3+, and Double UNet in the mIoU metric by a significant margin (p < 0.05; Figure 4). The highest performing mIoU came from the UNet++ but showed no significant difference between our model (p = 0.26).Discussion

The models that underperformed gives us an insight into how attention blocks, ASPP blocks, atrous and transpose convolutions improve model generalizability. Instead, most models had a higher number of parameters, likely leading to an inability to generalize the test set. A common problem in DL networks is overfitting, which is the model fits its parameters too well to the training set. With a relatively small dataset and a large number of parameters, overfitting becomes common. To improve the generalizability of unseen data, efficient models with fewer parameters and mechanisms such as dropout can be used. Figure 5 illustrates the segmentation performance of each model on a single slice from the test set. Typical segmentation errors resulted from differentiating AF from cerebral spinal fluid, eyes, esophagus, bladder, and surrounding fat tissue.Conclusion

This study demonstrates an improved medical segmentation network for the automated segmentation of amniotic fluid using a fetal MRI dataset. The proposed AFNet shows that upsampling blocks in residual networks can be replaced with transpose convolutional blocks, and average pooling layers can be replaced with atrous convolutional blocks to improve performance. This algorithm is limited by the size of the dataset, the dataset’s modality only being T2-weighted MRIs, and the use of only this dataset. Future studies should refine and further develop AFNet and AF MRI datasets in order to improve their accuracy and efficiency.Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by NSERC-Discovery Grant RGPIN-2018-04155 (Sussman).Figures

Figure 1. AFNet architecture. Rectangles represent different blocks or functions in the network, while arrows represent the flow of data. A legend is shown below the network to color–code the differing model blocks. Unless otherwise indicated, the stride is 1 for convolutional layers. A fetal MRI input image of 512x512 is used to feed into the network and output a segmentation mask for amniotic fluid.

Figure 2. Proposed attention block architecture used in AFNet. A legend is shown below the network to color–code the differing model blocks. Unless otherwise indicated, the stride is 1 for convolutional layers.

Figure 3. Test results for baseline ResUNet++, AFNet noT, AFNet. The best results are shown in bold.

Figure 4. Averaged test results of our AFNet with comparable state-of-the-art models. The best results are shown in bold. (* statistically significant, p<0.05)

Figure 5. Pixel-wise comparison of segmentation masks. Coronal T2-weighted image of the gravid uterus. Prediction masks (dark blue) are overlaid with the ground truth mask (white). Light blue pixels signify a true positive overlap segmentation, dark blue pixels demonstrate a false positive segmentation, white pixels demonstrate a false negative segmentation, and grey pixels demonstrate a true negative segmentation.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/4355