4338

Efficient 13C-hyperpolarization of lactate using parahydrogen and proton exchange.1Radiology and Neuroradiology, MOIN CC and SBMI, UKSH, Kiel, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Hybrid & Novel Systems Technology, Hyperpolarized MR (Non-Gas), Hyperpolarized Lactate, Parahydrogen, Proton Exchange

Hyperpolarization of biological molecules1,2,3 is a promising approach for metabolic MR imaging. Hyperpolarization methods based on parahydrogen and proton exchange4,5 promise almost universal polarization of many molecules, but current polarization yields are relatively low. Here, we present a new variant of Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization relayed via proton exchange (PHIP-X), which we demonstrate using the important biomolecule lactate. Polarization transfer between labile and covalent bound protons at different fields, combined with an RF pulse sequence, enables significantly enhanced 13C polarization of lactate. We believe that this approach may be used as a general strategy for the polarization of various biomolecules.

Introduction

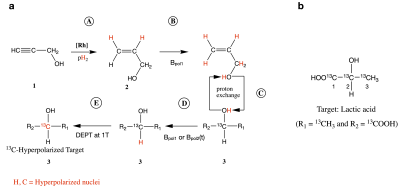

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of hyperpolarized contrast agents enables real time imaging of metabolism1 for diagnosis and monitoring of various diseases. Parahydrogen (pH2) based hyperpolarization methods are fast, less hardware and cost intensive than other methods1. Direct addition of pH2 to a molecule provides extremely strong signal enhancements under suitable conditions, but requires an unsaturated precursor (PHIP1). Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange (SABRE2) and PHIP using Side Arm Hydrogenation (PHIP-SAH3) overcame this shortcoming and strongly extended the range of polarizable molecules. More recently, SABRE-Relay4 and PHIP-X5 have increased the range of pH2-polarizable molecules further to basically all proton exchanging molecules. However, some challenges, mostly related to the hyperpolarization level, persist. For PHIP-X, first, pH2 is added to a precursor to generate a transfer agent whose spin structure is used to polarize a labile proton. This labile proton is exchanged with a labile proton of a target, from where the polarization is finally transferred to the target nucleus e.g. 13C. This scheme leaves much room for optimizations, e.g. polarization transfer among protons, chemical exchange rates, or 1H-13C transfer.Here, we introduce a new and general applicable variant (Fig. 1) for polarization transfer via proton exchange, where we use “spontaneous” polarization transfer among protons and an r.f. sequence for the 1H-13C transfer. Compared to previous results5, where no 13C-poolarization of lactate was observed, the new procedure significantly increased the 1-13C and 2-13C polarization of 13C3-lactate.

Method

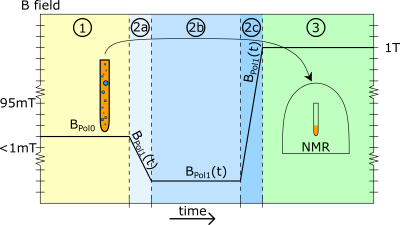

The transfer agent allyl alcohol (2 in Fig. 1) was hyperpolarized by injecting 98%-enriched pH2 at 30 bar into a solution of 175 mM of propargyl alcohol (1), 7 mM of [Rh(dppb)(COD)]BF4 ([Rh]) and 40 mM of 13C3-lactic acid in acetone-d6. Magnetic fields of Bpol1 = 0 - 95 mT (Fig. 1 and 2) were applied during hydrogenation. After 5 s, the hyperpolarized solution was transferred through a catheter and varing magnetic fields Bpol2(t) into an NMR at Bdetect = 1 T (spinsolve carbon 43, magritek). Proton exchange between the transfer agent and the target molecule was ongoing during the whole process, from hydrogenation to signal acquisition. In the NMR, a DEPT 135 sequence was used to transfer the polarization from a covalent bound proton to 2-13C and 3-13C of lacate (JCH = 145 Hz was used in the DEPT135 sequence). The polarization was quantified with respect to the signal at thermal equilibrium.Results

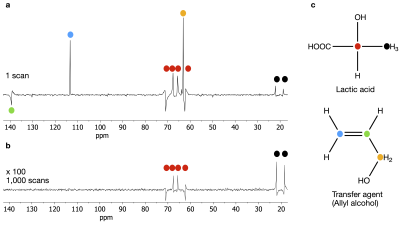

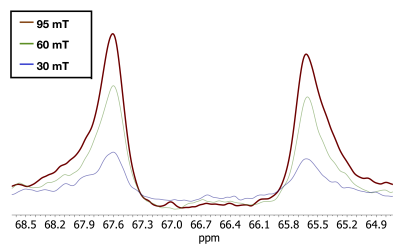

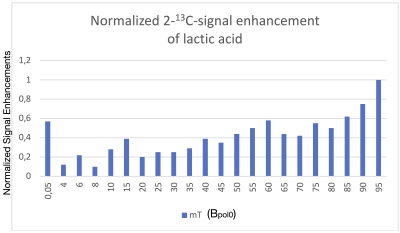

The implementation of the polarization scheme (Fig. 1) into our home-build polarizer provided about 100-fold signal amplifications for the 2-13C-nuclei (red dot in fig. 3) and 50-fold signal amplifications for the 3-13C-nuclei (black dot in fig. 3) of lactic acid in a 1T NMR. This is a significant advancement compared to previous procedures using PHIP-X5, where no 13C-polarization of lactate was observed. The 2-13C-nuclei showed stronger signal enhancements compared to the 3-13C-nuclei, probably because of its direct connection to the hydroxy group containing the labile proton. Note that carbon atoms without direct bonds to hydrogen atoms are not visible in a DEPT sequence. The achieved signal amplification showed a dependency (Fig. 4 and 5) on the field Bpol0 applied during hydrogenation with pH2. There is a general tendency of higher signal enhancements towards higher Bpol0-fields and there are local maxima at 15 mT and 60 mT.Disscusion

The new polarization variant (scheme in Fig. 1) significantly improved the PHIP-X hyperpolarization of lactate (Fig. 3). We believe that two factors were essential for this: a) using free evolution to transfer the polarization between labile and covalent bound protons (both in transfer and target molecule) and b) to polarize 13C using DEPT with a covalent bound proton. Still, much of the close-to-unity 1H polarization (~40%) of the transfer agent is lost during the process. The reason for this maybe that the polarization is distributed to too many protons, that the proton-proton transfer is not yet efficient enough (e.g. from pH2 protons to the labile proton in the transfer agent, and from labile to covalent 13C-bound protons in the target), or that the polarization is transferred to molecules other than the target (e.g. water as impurity, reaction side products or unconsumed precursor). In addition, the chemical exchange rates can be optimized as well by using a different solvent system.Hence, polarization transfer via proton exchange has potential to become an almost universal applicable method for hyperpolarization. However, this requires at least complex optimizations.

Conclusion

The presented approach allowed us to significantly improve the hyperpolarization of 13C nuclei of biomolecules. This is a promising development for PHIP-X, although other methods provide higher yields still (i.e. DNP). Once optimized, however, polarization transfer via proton exchange has potential to become an almost universal method for hyperpolarization, so that further investigations and optimizations are warranted.Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by the Emmy Noether Program “Metabolic and Molecular MR” (HO 4604/2-2), the research training circle “Materials for Brain” (GRK 2154/1-2019), DFG-RFBR grant (HO 4604/3-1, No 19-53-12013), Cluster of Excellence “Precision Medicine in Inflammation” (PMI 2167), German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the framework of the e:Med research and funding concept (01ZX1915C). Kiel University and the Medical Faculty are acknowledged for supporting the Molecular Imaging North Competence Center (MOIN CC, MOIN 4604/3). MOIN CC was founded by a grant from the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Zukunftsprogramm Wirtschaft of Schleswig-Holstein (Project no. 122-09-053). The Russian team thanks the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (Grant 19-53-12013) for financial support.References

[1] Jan-Bernd Hövener et. al.: Parahydrogen-Based Hyperpolarization for Biomedicine. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2018 Aug 27; 57(35): 11140–11162.

[2] Ralph W. Adams, Juan A. Aguilar, Kevin D. Atkinson, Michael J. Cowley, Paul I. P. Elliott, Simon B. Duckett, Gary G. R. Green, Iman G. Khazal, Joaquín López-Serrano, and David C. Williamson: Reversible Interactions with para-Hydrogen Enhance NMR Sensitivity by Polarization Transfer. Science, 323 5922 1708-1711 (2009) DOI: 10.1126/science.1168877

[3] Reineri, F., Cavallari, E., Carrera, C. et al.: Hydrogenative-PHIP polarized metabolites for biological studies. Magn Reson Mater Phy 34, 25–47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-020-00904-x

[4] Wissam Iali, Peter J. Rayner and Simon B. Duckett: Using parahydrogen to hyperpolarize amines, amides, carboxylic acids, alcohols, phosphates, and carbonates. Sci. Adv. 2018; 4: eaao6250.

[5] Kolja Them, Frowin Ellermann, Andrey N. Pravdivtsev, Oleg G. Salnikov, Ivan V. Skovpin, Igor V. Koptyug, Rainer Herges, and Jan-Bernd Hövener: Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization Relayed via Proton Exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 34, 13694–13700.

Figures

Scheme of the proposed method (a): pH2 is add (A) to a propargyl alcohol (1) in order to generate the hyperpolarized transfer agent (2). Due to the magnetic field Bpol0, net polarization (red) is transferred to labile protons of 1, which participate in proton exchange with labile protons of 2 (C). Bpol0 as well as Bpol1(t) enable a polarization of a proton directly connected to the 13C target nuclei (D). A DEPT sequence (E) then polarizes 13C-nuclei of target molecules (here lactic acid, b).

Scheme for the magnetic fields acting on the sample. In the first 5 seconds during hydrogenation a static field BPol0 is applied. Next, the solution is shuttled into the high field of an NMR spectrometer. During this shuttling the magnetic field BPol1(t) first decreases to the earth field, which acts for about 1 second, and then increases until the high field (1T) of the spectrometer is reached. Finally, a DEPT sequence is started immediately after arrival of the sample.

13C PHIP-X NMR spectrum (a) after injection of pH2 into a solution of 40 mM of 13C3-lactic acid (c), 7 mM of [Rh] and 173 mM of 1 in 900 µl acetone-d6. The colored dots indicate carbon atoms and connect them with signals of the spectrum. The 2-13C- and 3-13C-nuclei showed significant enhancements compared to the thermal spectrum (b). Note that a carbon atom without a direct bond to a hydrogen atom is not visible in a DEPT sequence.

Magnified view of the 2-13C resonance of 13C3-lactic acid polarized by PHIP-X at Bpol1 = 30, 60 and 90 mT. Note that the signal increased with increasing Bpol0, a trend that was observed for many, but not all, fields (Fig. 5).

Normalized 2-13C NMR signal enhancement of 13C3-lactic acid polarized by PHIP-X as function of Bpol0. While the polarization increased with increasing Bpol0 in general, several local minimal and maxima were observed. Simulations indicated that the signal decreases strongly for Bpol0 > 100 mT (not shown). Each bar represents an average of two experiments.