4335

An open-source echo-planar imaging sequence for hyperpolarized 13C MRI1Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Hyperpolarized MR (Non-Gas), Hyperpolarized MR (Non-Gas)

HP 13C MR imaging in humans has largely been restricted to GE scanners. To facilitate a human HP 13C imaging program at our institution and expand the translational potential of HP 13C MRI in general, we have developed a 3D symmetric EPI sequence for imaging HP 13C agents on Siemens scanners. Sequence development was performed using Pulseq, a flexible open-source tool for prototyping platform-agnostic pulse sequences. Metabolites were selectively excited using spectral-spatial RF pulses. Optional acceleration was achieved using partial Fourier undersampling in the slice direction. The sequence was tested using a thermally polarized phantom and a HP [1-13C]pyruvate phantom.

Introduction

Hyperpolarized (HP) 13C agents typically have short lifetimes (~1 min) and generate multiple metabolites. Therefore, pulse sequences for imaging HP 13C agents must be fast and capable of resolving several different chemical shifts. Currently, a popular choice in the field is echo-planar imaging (EPI) with spectral-spatial RF excitation (1,2). The spectral-spatial RF pulse selectively excites a metabolite of interest, and then an image is quickly acquired using the EPI readout.Most of the pulse sequences capable of imaging HP 13C in humans have been implemented on GE scanners. HP 13C MRI on Siemens scanners has largely been restricted to alternative sequences, such as chemical shift imaging (3), echo-planar spectroscopic imaging (4), and balanced steady-state free precession (5). Moreover, the existing Siemens sequences have all been created with the IDEA platform, complicating the sharing of sequences between research groups.

To fill the current gap in the field, we have developed a symmetric EPI sequence for imaging HP [1-13C]pyruvate and its metabolites on Siemens MRI scanners. This sequence was created using Pulseq (6), an open-source package for prototyping platform-independent pulse sequences.

Methods

Sequence development

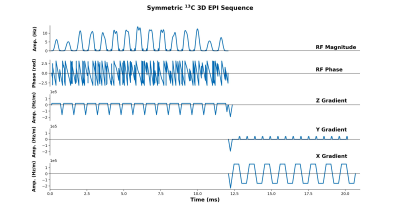

A 3D symmetric EPI sequence (Figure 1) was created using the Pulseq MATLAB package (https://github.com/pulseq/pulseq). The sequence begins with a spectral-spatial RF pulse designed to selectively excite a resonance of interest (e.g., pyruvate). This pulse was created using the “Spectral-Spatial RF Pulse Design for MRI and MRSI” MATLAB package (https://github.com/LarsonLab/Spectral-Spatial-RF-Pulse-Design). Next, a 3D EPI readout with phase encoding along the Z and Y axes was performed. Using this approach, a single 16 x 16 plane of k-space was acquired in approximately 21 ms. To decrease the time required for acquiring a full 3D image, we applied partial Fourier undersampling in the slice direction.

Phase Correction

To remove the N / 2 ghosting artifacts inherent to symmetric EPI, we acquired 13C reference scans (i.e., a scan without any phase encoding gradients). The constant and linear phase shifts between odd and even k-space lines was then computed from the reference scan and applied to the 13C EPI data (7). We also followed the approach developed by Gordon et al. (1) and experimented with using 1H reference scans to correct the 13C EPI data.

MR imaging

Experiments were performed using a 3T Siemens Prisma scanner with the Pulseq interpreter sequence. A custom-built 13C paddle surface coil (15cm x 30cm) and transmit-receive switch provided signal excitation and reception. A thermally polarized ethylene glycol phantom (1-gallon, natural abundance 13C) was used for initial testing. Dynamic imaging was also performed following the injection of ~10 mL of 150 mM HP [1-13C]pyruvate into a 1-gallon water phantom. Polarization of [1-13C]pyruvate was performed using a 5 T GE SPINlab hyperpolarizer.

Results

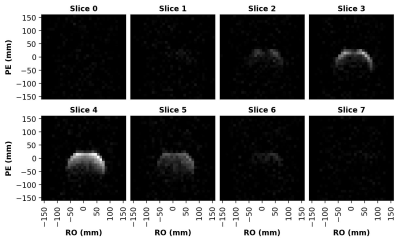

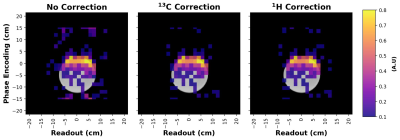

We first acquired a 3D image of a large thermally polarized ethylene glycol phantom (Figure 2) using the EPI sequence described in Figure 1. 13C signal was detectable in several 4 cm thick slices, although only the portion of the phantom nearest the surface coil was visible. Next, we compared phase correction using a 13C reference scan to correction using a 1H reference scan (Figure 3). As expected (1), the 1H reference scan was as effective as the 13C reference scan at removing the N / 2 ghosting artifacts.Finally, we tested the ability of our sequence to image a HP agent. Figure 4 shows several images taken at 5 s intervals following the injection of HP [1-13C]pyruvate into a water phantom. Pyruvate signal was detectable in phantom images for well over a minute after the injection began.

Discussion

We have successfully developed a 3D symmetric EPI sequence for imaging HP [1-13C]pyruvate on a Siemens 3T scanner. This is an important step in translating HP 13C MRI to human studies at our institution, and wider translation of HP 13C MRI in general. Currently, only one of the 15 sites that has translated HP 13C MRI into humans has used a Siemens MRI scanner (8). Therefore, prior to initiating human studies, we need a reliable and effective pulse sequence that works on the Siemens platform.We chose a metabolite-specific symmetric 3D EPI acquisition for several reasons. First, the use of spectral-spatial RF pulses to selectively image each 13C metabolite has proven to be very effective (1,2). One advantage of spectral-spatial pulses is that a different flip angle can be placed on each metabolite, with higher flip angles on metabolites on the injected substrate (9). Second, a symmetric EPI readout produces higher SNR images than slower readouts such as flyback EPI (1). Although symmetric readouts are prone to ghosting artifacts, we verified that these artifacts can be removed using a 1H reference scan (1). This is an improvement over using a 13C reference scan as no non-renewable HP magnetization is expended. Finally, a 3D readout with partial Fourier in the slice direction should significantly reduce acquisition times for human studies where large number of slices are required.

Conclusion

We have created an open-source sequence for HP 13C MR imaging on Siemens scanners. Additional experiments are needed to confirm the effectiveness of our sequence for imaging HP 13C agents in humans.Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge technical support from Xinzhou Li, Uday Krishnamurthy, and Bernd Stoeckel (Siemens Healthineers), as well as the assistance of James Quirk, Cihat Eldeniz, and Linda Hood (Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology).References

1. Gordon JW, Vigneron DB, Larson PEZ. Development of a symmetric echo planar imaging framework for clinical translation of rapid dynamic hyperpolarized 13C imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(2):826–32.

2. Geraghty BJ, Lau JYC, Chen AP, Cunningham CH. Dual-Echo EPI sequence for integrated distortion correction in 3D time-resolved hyperpolarized 13C MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79(2):643–53.

3. Eldirdiri A, Clemmensen A, Bowen S, Kjær A, Ardenkjær-Larsen JH. Simultaneous imaging of hyperpolarized [1,4-13C2]fumarate, [1-13C]pyruvate and 18F–FDG in a rat model of necrosis in a clinical PET/MR scanner. NMR Biomed. 2017;30(12):1–9.

4. Eldirdiri A, Posse S, Hanson LG, Hansen RB, Holst P, Schøier C, et al. Development of a Symmetric Echo-Planar Spectroscopy Imaging Framework for Hyperpolarized 13C Imaging in a Clinical PET/MR Scanner. Tomogr (Ann Arbor, Mich). 2018;4(3):110–22.

5. Müller CA, Hundshammer C, Braeuer M, Skinner JG, Berner S, Leupold J, et al. Dynamic 2D and 3D mapping of hyperpolarized pyruvate to lactate conversion in vivo with efficient multi-echo balanced steady-state free precession at 3 T. NMR Biomed. 2020;33(6):1–16.

6. Layton KJ, Kroboth S, Jia F, Littin S, Yu H, Leupold J, et al. Pulseq: A rapid and hardware-independent pulse sequence prototyping framework. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(4):1544–52.

7. Bernstein MA, King KF, Zhou XJ. Handbook of MRI Pulse Sequences [Internet]. Elsevier; 2004.

8. Rider OJ, Apps A, Miller JJJJ, Lau JYC, Lewis AJM, Peterzan MA, et al. Noninvasive in vivo assessment of cardiac metabolism in the healthy and diabetic human heart using hyperpolarized 13C MRI. Circ Res. 2020;725–36.

9. Blazey T, Reed GD, Garbow JR, von Morze C. Metabolite-Specific Echo-Planar Imaging of Hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyruvate at 4.7 T. Tomogr (Ann Arbor, Mich) [Internet]. 2021 Sep 15;7(3):466–76.

Figures

Figure 2: 3D 13C image of a thermally polarized cylindrical ethylene glycol phantom. Image acquisition consisted of a 32x32x8 grid with a partial Fourier fraction of 0.75 in the slice direction, a 32 cm3 FOV, and 8 averages. The intensity variation within an axial slice is largely due to the B1 profile of our custom-built 13C surface coil. Phase correction was performed using a 13C reference scan.

Figure 4: Dynamic imaging following the injection of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate into a water phantom (left circle). Acquisition parameters were as follows: 16x16x8 grid, axial slices, 0.75 partial Fourier in the slice direction, temporal resolution = 5 s, TR = 21 ms, Flip Angle = 10°, and FOV = 32x32x20 cm3. Intensity of the HP polarized image is shown in color over a high resolution 1H image in gray (top). Average time course over the top half of the water phantom (bottom). Injection began at ~10 seconds.