4332

Effects of Gadolinium on the Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of [15N3] Metronidazole1Radiology Department, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, MGH, Charlestown, MA, United States, 2Polarize ApS, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 3Department of Chemistry, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, United States, 4Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States, 5Department of Health Technology, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark, 6Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russian Federation

Synopsis

Keywords: Hyperpolarized MR (Non-Gas), Contrast Agent, Contrast Mechanism

In this work, we studied the dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) process of [15N3]metronidazole (MNZ), an FDA-approved antibiotic that achieved good polarization (~6%) with very short polarization build-up time constants (~12min). We used Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy to show that a sample of [15N3]MNZ + trityl AH111501 had narrower EPR linewidth and larger magnitude than AH111501 alone, indicating an efficient polarization transfer from the radical electrons to 15N and supporting our observations of fast DNP buildup. We also demonstrated that an addition of gadolinium-based compound to the [15N3]MNZ +AH111501 sample broadened the EPR spectrum and prolonged DNP buildup as observed.Iintroduction

The hyperpolarization of 15N-labeled compounds with Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (DNP) technique typically takes a long time (several hours)[1–3]. The formulation of DNP samples is of central importance to ensure the efficiency of the hyperpolarization process. The nature and concentration of the radical, the pH of the solution, and the concentration of the analyte are some of the parameters that need to be optimized[4–7]. For our dissolution-DNP(d-DNP) experiments, we use trityl AH111501, a radical that is used in the 13C-pyruvate DNP samples for hyperpolarized 13C-pyruvate metabolic imaging[7–11]. In DNP, both the microwave irradiation and the electron relaxation mechanisms are responsible for the polarization transfer from electrons to the analyte. In order to speed up the DNP process, gadolinium derivates are often added to the DNP samples to increase electron relaxation rate, which in turn speeds up the hyperpolarization process[4,5,12]. The radical and gadolinium concentrations have to be carefully chosen since the electron relaxation mechanism is also at the origin of the analyte’s paramagnetic relaxation[13], which can deplete the analyte’s hyperpolarization at a faster rate than it is created.Previously, we demonstrated the hyperpolarization of [15N3]metronidazole (MNZ), an FDA-approved antibiotic that has been shown to have minutes-long T1 relaxation times in liquid state and has been injected in rats to observe its long-lasting hyperpolarized signal in the brain[14]. The MNZ samples optimized for DNP have polarization build-up time constants of ~13 min reaching polarization levels of 6% without any addition of gadolinium. In this work, we investigated the effects of gadolinium on the hyperpolarization process of [15N3]MNZ by using Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy and by monitoring the DNP build-up of [15N3]MNZ.

Methods

All samples were hyperpolarized on a d-DNP polarizer (SpinAligner, Polarize, Denmark)[15] equipped with a broadband DNP probe and an RF circuit tuned to 15N. The 15N signal build-up was monitored periodically by a small RF flip-angle during the hyperpolarization process. The sample composition and DNP parameters were empirically optimized to best hyperpolarize [15N3]MNZ. Samples were prepared by dissolving 1.5 M [15N3]MNZ and 30mM tritylAH111501 in pure DMSO. A sample of 1.5 M [15N2]MNZ and 30 mM tritylAH11501 was also hyperpolarized to compare the DNP build-up with [15N3]MNZ. A commercial solution of 500 mM Dotarem(Guerbet LLC, New Jersey,USA), was added at 2-8mM concentrations.X-band continuous-wave EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker spectrometer equipped with a liquid nitrogen cryostat operating at 75-80 K, and with a microwave power of 0.2 mW.

Results

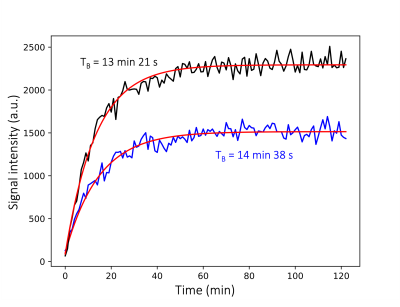

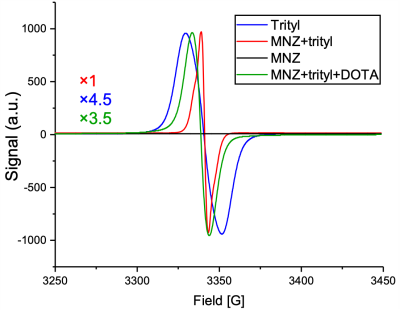

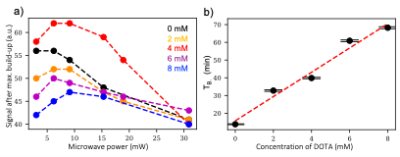

Without addition of gadolinium, [15N3]MNZ and [15N2]MNZ have short polarization build-up time constants of TB=13.35±0.32 min and T =14.63±0.40 min, respectively(Figure 1). The 15N HP signal values scale quantitatively S15N3/S15N2=3/2 reflecting the difference in the number of 15N-labeled sites (3vs.2).The EPR spectra of 4 different samples are displayed in Figure 2. Compared to the EPR spectrum of trityl along (blue), the trityl+[15N3]MNZ has a narrower EPR linewidth and higher magnitude (red), indicating an efficient polarization transfer from electrons to the 15N analyte[5]. The addition of Dotarem to trityl+[15N3]MNZ resulted in a broader EPR spectrum (i.e. wider linewidth) with lower magnitude (green), suggesting a reduced efficiency in the polarization transfer. This phenomenon supports the finding that the additions of Dotarem increase the build-up time constants(Figure 3b). The polarization levels do not seem to improve significantly at any Dotarem concentration either(Figure 3a).

Discussion

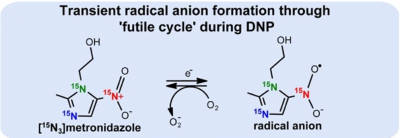

The results show that the addition of Dotarem clearly causes stepwise quenching of otherwise efficient polarization build-up. To rationalize this puzzling observation, we have two hypotheses.In the first hypothesis, trityl radical interacts with [15N3]MNZ establishing reversible [15N3]MNZ radical anion formation through a ‘futile cycle’[16] during DNP process(Figure 4). The trityl free electron is therefore effectively shared with [15N3]MNZ leading to radical anion formation in the nitro group. Since MNZ and trityl are planar aromatic molecules, the interaction between MNZ and trityl may be additionally enhanced through π-π stacking. Since this new radical anion is spatially substantially closer to the 15N centers, it acts as a more potent source of polarization. The addition of DOTA has possibly reduced the electron relaxation further and hence, diminishes the efficiency of polarization transfer from electrons to the analyte slowing down the polarization build-up.

Another explanation for the fast buildup of [15N3]MNZ DNP would be the formation of trityl dimers, as has been reported for other DNP samples containing trityl[3]. While hyperolarizing 15N-choline, the addition of tetramethylammonium(TMA) salts induced the formation of trityl dimers[3] that increased the electron relaxation processes due to the close proximity of the paramagnetic centers. Again, the addition of Dotarem increases the electron's relaxation and additionally, DOTA, the ligand present in Dotarem, can enhance the formation of trityl dimers, increasing electron relaxation further and slowing down the polarization build-up.

Conclusion

Contrary to what has been widely practiced, the addition of Dotarem does not act as a polarization booster for [15N3]MNZ, which is otherwise very efficient. We will continue testing the hypotheses and identify the mechanism of action that explains the effects of gadolinium in the DNP of [15N3]MNZ. We will also continue to investigate how to utilize MNZ properties in DNP to potentially boost DNP process and to understand what radical properties could increase the efficiency of [15N3]MNZ polarization build-up.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH funds S10OD021768, R21GM137227, R01EB029829. We thank Dr. Jonathan R. Birchall for pilot solubility testing of metronidazole in DMSO, and Dr. Kalina Ranguelova and Dr. James Kempf from Bruker Biospin Corp. for their contribution to the EPR studies.References

1] C. Cudalbu, A. Comment, F. Kurdzesau, R. B. van Heeswijk, K. Uffmann, S. Jannin, V. Denisov, D. Kirik, R. Gruetter, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2010, 12, 5818.

[2] C. Morze, J. A. Engelbach, G. D. Reed, A. P. Chen, J. D. Quirk, T. Blazey, R. Mahar, C. R. Malloy, J. R. Garbow, M. E. Merritt, Magn Reson Med 2021, 85, 1814–1820.

[3] I. Marin-Montesinos, J. C. Paniagua, M. Vilaseca, A. Urtizberea, F. Luis, M. Feliz, F. Lin, S. van Doorslaer, M. Pons, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2015, 17, 5785–5794.

[4] F. Jähnig, G. Kwiatkowski, A. Däpp, A. Hunkeler, B. H. Meier, S. Kozerke, M. Ernst, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2017, 19, 19196–19204.

[5] A. Capozzi, S. Patel, W. T. Wenckebach, M. Karlsson, M. H. Lerche, J. H. Ardenkjær-Larsen, J Phys Chem Lett 2019, 10, 3420–3425.

[6] D. Guarin, S. Marhabaie, A. Rosso, D. Abergel, G. Bodenhausen, K. L. Ivanov, D. Kurzbach, J Phys Chem Lett 2017, 8, 5531–5536.

[7] J. H. Ardenkjaer-Larsen, Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2016, 264, 3–12.

[8] S. J. Kohler, Y. Yen, J. Wolber, A. P. Chen, M. J. Albers, R. Bok, V. Zhang, J. Tropp, S. Nelson, D. B. Vigneron, J. Kurhanewicz, R. E. Hurd, Magn Reson Med 2007, 58, 65–69.

[9] A. Comment, Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2016, 264, 39–48.

[10] J. Kurhanewicz, D. B. Vigneron, J. H. Ardenkjaer-Larsen, J. A. Bankson, K. Brindle, C. H. Cunningham, F. A. Gallagher, K. R. Keshari, A. Kjaer, C. Laustsen, D. A. Mankoff, M. E. Merritt, S. J. Nelson, J. M. Pauly, P. Lee, S. Ronen, D. J. Tyler, S. S. Rajan, D. M. Spielman, L. Wald, X. Zhang, C. R. Malloy, R. Rizi, Neoplasia 2019, 21, 1–16.

[11] Z. J. Wang, M. A. Ohliger, P. E. Z. Larson, J. W. Gordon, R. A. Bok, J. Slater, J. E. Villanueva-Meyer, C. P. Hess, J. Kurhanewicz, D. B. Vigneron, Radiology 2019, 291, 273–284.

[12] M. Kaushik, T. Bahrenberg, T. v. Can, M. A. Caporini, R. Silvers, J. Heiliger, A. A. Smith, H. Schwalbe, R. G. Griffin, B. Corzilius, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2016, 18, 27205–27218.

[13] A. Abragam, M. Goldman, Reports on Progress in Physics 1978, 41, 395–467.

[14] D. O. Guarin Bedoya, E. E. Hardy, A. Smoilenko, S. Joshi, J. Stockman, J. H. Ardnkjaer-Larsen, M. S. Rosen, B. Goodson, T. Theis, E. Chekmenev, Y.-F. Yen, in 0th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicin, London, 2022, p. 0838.

[15] J. H. Ardenkjær‐Larsen, S. Bowen, J. R. Petersen, O. Rybalko, M. S. Vinding, M. Ullisch, N. Chr. Nielsen, Magn Reson Med 2019, 81, 2184–2194.

[16] A. Salahuddin, S. M. Agarwal, F. Avecilla, A. Azam, Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2012, 22, 5694–5699.

Figures