4312

Parameter inference using continuous change in degenerate biophysical diffusion models1Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, FMRIB, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, Microstructure, biophysical diffusion modelling

Biophysical modelling of diffusion MRI (dMRI) may elucidate key microstructural features. However, most models include many input parameters, making simultaneous estimations of all parameters ill-posed. To overcome this, the recently published Bayesian framework EstimatioN for CHange (BENCH) characterises changes (variation) in parameters across multiple measurements/samples, rather than inferring the actual parameters from a single measurement/sample. BENCH has been previously applied to understand group-wise changes (e.g., patients vs. controls) in biophysical parameters. Here, we adapted BENCH to interpret situations of continuous change and validate its behaviour using synthetic dMRI data from numerical simulations.Introduction

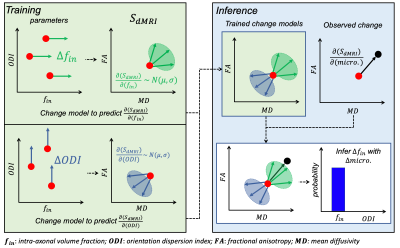

Biophysical models aim to translate dMRI signals to biologically-meaningful parameters. However, models that adequately describe the tissue microstructure require many input parameters. Consequently, parameter estimation via model inversion is degenerate, with different combinations of parameters explaining the same dMRI data equally well, making robust parameter estimation challenging. A common approach to overcome this is to constrain some parameters and estimate other parameters-of-interest; this can lead to biased parameter estimation1.The Bayesian EstimatioN of CHange (BENCH)2 framework circumvents model inversion by characterising the effect of parameter changes on measurements, instead of estimating the parameters themselves. Briefly (Figure 1), BENCH uses a generative model to train “change models” where, for a set of input parameters (param.), we calculate the diffusion signal (SdMRI) and the direction of change (∂SdMRI/∂param.) induced by a small change in each model parameter. The central concept is that these change models’ outputs can be compared with an observed variation in SdMRI in a dataset to infer the likelihood that a change in a model parameter explains the observed signal variation. Crucially, the degenerate model does not need to be inverted to infer parametric change.

Previously, BENCH was applied to infer parameter differences between two groups (patients vs. controls)2. Inferring continuous change opens up a broader range of applications e.g., relating to disability scores or microscopy-derived metrics; a continuous change framework confers the additional benefit of being able to consider multiple variables simultaneously.

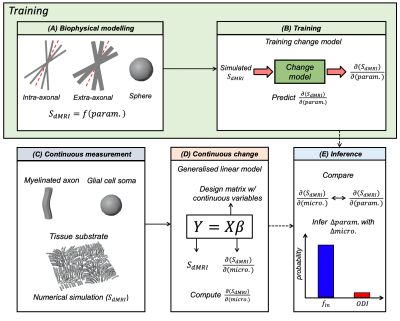

Here, we extend the BENCH framework to identify changes in continuous variables. We test this framework (Figure 2) on synthetic data from numerical simulations, demonstrating detection of subtle microstructural changes in highly degenerate models. Ultimately, we are interested in applying this to dMRI and microscopy metrics derived from the same tissue samples.

Methods

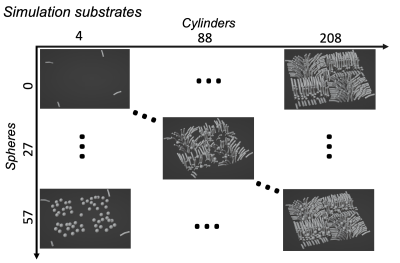

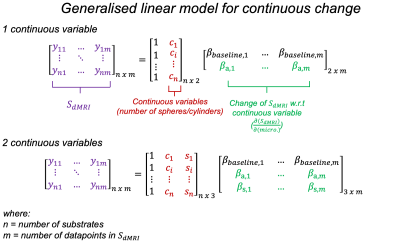

Here, we simulate dMRI signals in a synthetic substrate representing white matter tissue. It consists of a field of dispersed undulating cylinders ("axons") and spheres ("glia") (Figure 3). We use Monte Carlo simulations to estimate diffusion signals for multiple substrates3,4,5. The continuous variables are how many cylinders and spheres are present in each substrate. Rather than working with the raw signals, we use a reduced representation (Figure 1 shows FA, MD as examples. Here, we use spherical harmonics).These continuous variables and associated diffusion signals are fed into the change framework (Figure 2). The continuous variables (X) are fit to the measured signals (Y) using a GLM (Figure 4). The resulting effect sizes (β) describe how much variance (change) across the measurements is explained by each continuous variable. Importantly, this framework can capture multiple continuous variables (n) and diffusion measurements (m).

Estimated βs (one per continuous variable) describe the direction of continuous change in the measurement space (∂SdMRI/∂micro.). These vectors can be compared to the ∂SdMRI/∂param. vectors learned during training for each biophysical model parameter. Inference consists of calculating the probability that the observed change can be explained by a given biophysical model parameter, given the Gaussian distributions learned in change model training. Technical details are shown in a previous publication2.

We consider two biophysical models (Figure 2A) based on the standard model6. One contains spheres7 and one does not, leading to different levels of degeneracy (8 vs. 5 parameters). This enables us to test whether the framework assigns sensible model parameters to the continuous variables, despite the models being uninvertable.

Results and Discussion

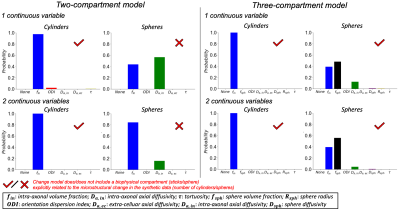

Figure 5 shows how a continuous change in either cylinders (axons), spheres (glial cell soma) or both, are attributed to parameter changes in both biophysical models (two- vs. three-compartment models).We first consider a change in one continuous variable (Figure 5 top row). Change in cylinders was correctly attributed to intra-axonal volume fraction (fin) in both two- and three-compartment models (~100%). The two-compartment model attributed changes in spheres with similar probability to fin and intra-axonal axial diffusivity (Da,in), reflecting reduced overall axial diffusivity due to restricted spheres. Given that the two-compartment model does not include spheres, this suggests that the change framework may provide distinct signatures of parameter change even for incomplete models. In the three-compartment model, a change in the sphere volume fraction (fsph) was found to be the most probable (~50%) explanation for the simulated change in spheres.

Next, we inferred change in either cylinders or spheres, whilst accounting for a confounding change in the other microstructure (2 continuous variables, Figure 5 bottom row). Predicted parameters are similar to the predictions above (change in 1 continuous variable) for both models, albeit with different prediction certainties. These suggest that BENCH robustly predicts one variable’s change even with another variable changing, provided the variables are not coupled.

Notably, changes in spheres are predicted with a lower certainty relative to changes in cylinders in the three-compartment model (45-55% vs. 100%). This may reflect smaller changes in the signal fraction associated with the spheres relative to cylinders.

These results demonstrate that this framework can detect subtle microstructural changes in highly degenerate models.

Conclusion

We present a framework to infer changes in continuous variables using degenerate biophysical models. In future work, we aim to apply this framework to relate real post-mortem dMRI to co-registered microscopy, and in-vivo dMRI to continuous clinical variables.Acknowledgements

AFDH and KLM contributed equally to this work. DZLK is supported by the Hrothgar Singaporean Clarendon Scholarship and the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences studentship. KLM, AFDH, MC, and SJ are supported by the Wellcome Trust (grants WT202788/Z/16/A, WT215573/Z/19/Z and WT221933/Z/20/Z). The Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging is supported by core funding from the Wellcome Trust (203139/Z/16/Z).References

1. Jelescu IO, Veraart J, Fieremans E, Novikov DS. Degeneracy in model parameter estimation for multi-compartmental diffusion in neuronal tissue. NMR in Biomedicine. 2016;29(1):33-47. doi:10.1002/nbm.3450

2. Rafipoor H, Zheng YQ, Griffanti L, Jbabdi S, Cottaar M. Identifying microstructural changes in diffusion MRI; How to circumvent parameter degeneracy. NeuroImage. 2022;260:119452. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119452

3. Cook PA, Bai Y, Nedjati-Gilani S, et al. Camino: Open-Source Diffusion-MRI Reconstruction and Processing. 14th Scientific Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006. p. 2759.

4. Hall MG, Alexander DC. Convergence and Parameter Choice for Monte-Carlo Simulations of Diffusion MRI. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2009;28(9):1354-1364. doi:10.1109/TMI.2009.2015756

5. Van Essen DC, Smith SM, Barch DM, et al. The WU-Minn Human Connectome Project: an overview. NeuroImage. 2013;80:62-79. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.041

6. Novikov DS, Fieremans E, Jespersen SN, Kiselev VG. Quantifying brain microstructure with diffusion MRI: Theory and parameter estimation. NMR in Biomedicine. 2019;32(4):e3998. doi:10.1002/nbm.3998

7. Stanisz GJ, Wright GA, Henkelman RM, Szafer A. An analytical model of restricted diffusion in bovine optic nerve. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1997;37(1):103-111. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910370115

8. Veraart J, Nunes D, Rudrapatna U, et al. Noninvasive quantification of axon radii using diffusion MRI. de Lange FP, Forstmann B, Forstmann B, Jbabdi S, Mulkern R, eds. eLife. 2020;9:e49855. doi:10.7554/eLife.49855

9. Kozlowski C, Weimer RM. An Automated Method to Quantify Microglia Morphology and Application to Monitor Activation State Longitudinally In Vivo. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31814. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031814

Figures