4304

Evidence of axon beading and loss of extracellular fluid following perfusion and fixation of the marmoset brain1Western University, London, ON, Canada, 2Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Microstructure, Microstructure

Previous work showed that advanced diffusion metrics (OGSE and μFA) are sensitive to microstructural changes between in vivo and ex vivo marmoset brain tissues. Here, we utilized Monte Carlo simulations to investigate potential microstructure changes that could be occurring during tissue perfusion and fixation. A comparison between simulations and experiments showed that beading and decreased extracellular space are in agreement with the experimental trends observed. Changing microstructural properties during these processes has implications for studies that compare ex vivo tissue samples with in vivo findings.Introduction

Although routinely used in clinics due to its sensitivity to severe cerebral vascular alterations, traditional diffusion MRI lacks the specificity and sensitivity to determine microstructural changes in the brain tissue. The use of oscillating gradients spin echo (OGSE) to control the diffusion time and spherical encoding to determine the microscopic anisotropy of the tissues can help to define the specific changes in the tissue under pathology.For instance, OGSE metrics have been shown to be sensitive to axonal caliper1 and abnormalities in the brain, such as tumors2 and ischemic stroke3. Microscopic fractional anisotropy (μFA) is insensitive to fiber orientation dispersion, contrasting the traditional MRI counterpart metric (FA), and has been shown to provide extra information in normal-appearing white matter (WM) lesions in multiple sclerosis4, can be used to detect different types of tumor5, and progression in Parkinson’s disease6.

In this work, we simulated hypothesized changes in the WM from in vivo to ex vivo and their effects on the OGSE and μFA metrics using the Monte Carlo method. Additionally, we compared these changes with experimental data from in vivo and ex vivo marmoset brains presented in the ISMRM 20227 and inferred potential changes in the tissue.

Methods

We acquired diffusion MRI in vivo and ex vivo in two adult common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus). In vivo data were acquired with the animals sedated with an intramuscular injection of ketamine at 20 mg/kg dosage, which was maintained using 1.5% isoflurane inhaled through a face mask for the duration of the scan. For the ex vivo scans, the animals were perfused using 0.1M sodium cacodylate and Heparin 10,000U/ml (200-300ml) followed by 2% Paraformaldehyde and 2.5% Glutaraldehyde (300ml). The brains were then harvested and transferred to 0.1M sodium cacodylate with 0.03% NaN3 after 96 hours, following the methods described by8. Before the scans, the brains were transferred to a tube with Crysto-lube and gauze, and kept in the scanner room overnight.The in vivo scans included OGSE protocol (0.6mm isotropic, TE/TR=54/17360ms, frequencies(directions) PGSE(9), 20(9), 48(6), and 75(4) Hz, b-values 0, 1, and 2ms/μm2, ~1h acquisition time) and μFA protocol (0.5x0.5x0.6mm3, TE/TR=43/6800, b-values 0, 0.7, 1.3, and 2 ms/μm2, ~1h acquisition time). The ex vivo scans included OGSE protocol (0.5mm isotropic, TE/TR=51/25000ms, frequencies(directions) PGSE(9), 20(9), 48(9), and 75(9) Hz, b-values 0, 2, and 4 ms/μm2, ~7h acquisition time) and μFA protocol (0.4x0.4x0.5mm3, TE/TR=35/18000, b-values 0, 2, and 4 ms/μm2, ~7h acquisition time). More details of the acquisition, preprocessing, and waveforms are shown in Figure 1.

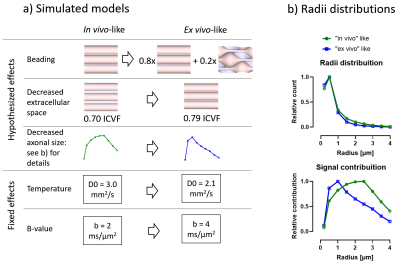

Monte Carlo diffusion simulations were performed using the Camino package9. We investigated changes in tubular shape geometries using customized mesh geometries. The hypothesized and known changes are shown in Figure 2 and included a range of radius from 0.2 to 4μm, a beaded/non-beaded fraction of 0% (in vivo) and 20% (ex vivo), and intracellular volume fraction of 0.70 (in vivo) and 0.79 (ex vivo). Changes in intrinsic diffusivity was taken into account by varying the free water diffusivity from 3mm2/s (in vivo) to 2.1mm2/s (ex vivo). We also used the same waveforms from the experimental acquisition in the simulations. The other parameters of the simulations were: 100,000 spins, 2000 time-steps, and about 4 hours per simulation of running time.

Results

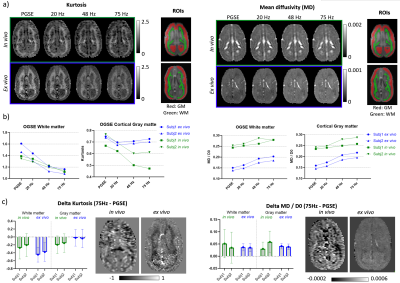

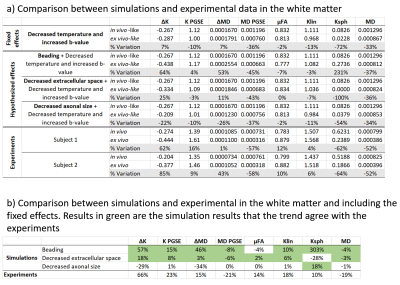

Figure 3 shows the kurtosis and mean diffusivity (MD) maps and metrics from the OGSE protocol. Figure 4 shows the maps and metrics for the μFA protocol. Figure 5a shows the trends identified in the simulations. Figure 5b shows the comparison of simulated and experimental data after correcting for the fixed effects (b-value and temperature), highlighting the changes in the simulations that correspond to the trends seen in the experimental data.Discussion

Comparing differences between in vivo and ex vivo tissue microstructure is important since some models and ex vivo studies often make inferences in the in vivo tissues from ex vivo data. Figure 5a shows that the fixed effects in the experiments (scanning at room temperature and increased b-values in the ex vivo protocol, as it is usually acquired) change most of the metrics, most strongly in MD and spherical kurtosis.Our simulations show that our hypothesized effects of beading and decreased extracellular space mostly match the trends observed in the experimental data (see Figure 5b). The exceptions of the μFA metric in the beading simulations and the spherical kurtosis metric in the decreased extracellular space simulations suggest that these two changes are happening simultaneously. The loss of extracellular fluid is consistent with brain volume decreases that are known to occur after fixation. While beading from ischemia is likely mitigated by perfusion fixation used during sample preparation, beading could also be induced by the changing osmotic balance and changes in cell membrane tension (e.g., similar to 10) during the fixation process as extracellular fluid is lost.

Conclusion

This work provides evidence for specific microstructural changes that occur during the fixation process, which is relevant for studies that compare in vivo findings to ex vivo tissue characterization. Future work will include imaging with μCT and histology and the analysis of their correlation with the advanced diffusion microstructure metrics.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (BrainsCAN) and the Canada Research Chairs Program.References

(1) Siow, B.; Drobnjak, I.; Ianus, A.; Christie, I. N.; Lythgoe, M. F.; Alexander, D. C. Axon Radius Estimation with Oscillating Gradient Spin Echo (OGSE) Diffusion MRI. Diffus. Fundam. 2013, 18 (1), 1–6.

(2) Colvin, D. C.; Yankeelov, T. E.; Does, M. D.; Yue, Z.; Quarles, C.; Gore, J. C. New Insights into Tumor Microstructure Using Temporal Diffusion Spectroscopy. Cancer Res. 2008, 68 (14), 5941–5947. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0832.

(3) Baron, C. A.; Kate, M.; Gioia, L.; Butcher, K.; Emery, D.; Budde, M.; Beaulieu, C. Reduction of Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Contrast of Acute Ischemic Stroke at Short Diffusion Times. Stroke 2015, 46 (8), 2136–2141. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008815.

(4) Andersen, K. W.; Lasič, S.; Lundell, H.; Nilsson, M.; Topgaard, D.; Sellebjerg, F.; Szczepankiewicz, F.; Siebner, H. R.; Blinkenberg, M.; Dyrby, T. B. Disentangling White-Matter Damage from Physiological Fibre Orientation Dispersion in Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Commun. 2020, 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcaa077.

(5) Szczepankiewicz, F.; Lasič, S.; van Westen, D.; Sundgren, P. C.; Englund, E.; Westin, C.-F.; Ståhlberg, F.; Lätt, J.; Topgaard, D.; Nilsson, M. Quantification of Microscopic Diffusion Anisotropy Disentangles Effects of Orientation Dispersion from Microstructure: Applications in Healthy Volunteers and in Brain Tumors. NeuroImage 2015, 104, 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.057.

(6) Ikenouchi, Y.; Kamagata, K.; Andica, C.; Hatano, T.; Ogawa, T.; Takeshige-Amano, H.; Kamiya, K.; Wada, A.; Suzuki, M.; Fujita, S.; Hagiwara, A.; Irie, R.; Hori, M.; Oyama, G.; Shimo, Y.; Umemura, A.; Hattori, N.; Aoki, S. Evaluation of White Matter Microstructure in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease Using Microscopic Fractional Anisotropy. Neuroradiology 2020, 62 (2), 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-019-02301-1.

(7) Santini, T.; Rahman, N.; Shim, A.; Inoue, W.; Everling, S.; Baron, C. Oscillating Gradient (OGSE) and Microscopic Anisotropy Diffusion in the in Vivo and Ex Vivo Marmoset Brain. In ISMRM 2022; London UK.

(8) Foxley, S.; Sampathkumar, V.; De Andrade, V.; Trinkle, S.; Sorokina, A.; Norwood, K.; La Riviere, P.; Kasthuri, N. Multi-Modal Imaging of a Single Mouse Brain over Five Orders of Magnitude of Resolution. NeuroImage 2021, 238, 118250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118250.

(9) Hall, M. G.; Alexander, D. C. Convergence and Parameter Choice for Monte-Carlo Simulations of Diffusion MRI. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2009, 28 (9), 1354–1364. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2009.2015756.

(10) Budde, M. D.; Frank, J. A. Neurite Beading Is Sufficient to Decrease the Apparent Diffusion Coefficient after Ischemic Stroke. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107 (32), 14472–14477. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1004841107.

Figures