4303

Multi-echo NODDI for the study of tissue compartmentalisation in transient ischaemic stroke: initial insights1Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine 4, Forschungszentrum Jülich, Jülich, Germany, 2Institute of Biomedical Engineering and Nanomedicine, National Health Research Institutes, Miaoli, Taiwan, 3Institute of Medical Device and Imaging, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan, 4Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany, 5JARA – BRAIN – Translational Medicine, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany, 6Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine – 11, Forschungszentrum Jülich, Jülich, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Stroke, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, NODDI, ischemia, multi-echo, transverse relaxation, intra-neurite, extra-neurite

Neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) has been broadly used in diffusion MRI for the characterisation of tissue microstructure in healthy ageing and the diseased brain. However, the compartment-specific volume fractions provided by NODDI suffer from echo-time (TE) dependence due to differences in the compartment-specific transverse relaxation times. The recently proposed multi-TE NODDI (MTE-NODDI) model provides both TE-independent compartmental volume fractions and compartment-specific transverse relaxation times. Here we aim to assess the benefits and limitations of using MTE-NODDI for studying the brain tissue microstructure affected by transient ischaemic stroke in MCAo animal models.Introduction

Neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) has been widely used for the investigation of tissue microstructure in both healthy conditions and disease1,2. However, studies have demonstrated that the compartment-specific transverse relaxation times (T2) in vivo are generally different3,4, causing the tissue compartment volume fractions as assessed by NODDI to be T2-weighted and TE-dependent5. In order to overcome this limitation, Gong et al.5 recently proposed the multi-TE NODDI (MTE-NODDI) model for the simultaneous analysis of diffusion- and the T2-weighted MRI signal. The model provides not only TE-independent compartmental volume fractions but also compartment-specific T25. Thus, the aim of this study is to assess the benefits and limitations of using MTE-NODDI for the characterisation of ischaemic tissue microstructure in middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) animal models.Methods

Theory. The diffusion- and T2-weighted signal for the MTE-NODDI model is written as follows1,5: $$S=S_0\left[f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{iso}S_\mathrm{iso}e^{-\frac{TE}{T_{2,\mathrm{iso}}}}+\left(1-f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{iso}\right)\left(f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}S_\mathrm{in}e^{-\frac{TE}{T_{2,\mathrm{in}}}}+\left(1-f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}\right)S_\mathrm{en}e^{-\frac{TE}{T_{2,\mathrm{en}}}}\right)\right] \tag{1}$$ where $$$S_{0}$$$ is the proton density; $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{iso}$$$ and $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}$$$ are the TE-independent, isotropic and intra-neurite volume fractions; $$$S_k$$$ (k=iso, in, en) are the isotropic, intra- and extra-neurite normalised diffusion-weighted signals1; and $$$T_{2,\mathrm{iso}}$$$, $$$T_{2,\mathrm{in}}$$$ and $$$T_{2,\mathrm{en}}$$$ are the compartment-specific T2 times5. For parameter estimation, Gong et al.5 proposed a multi-step approach: i) fit the conventional NODDI to each TE dataset separately to obtain the TE-dependent compartmental fractions $$$f_\mathrm{iso}\left(TE\right)$$$ and $$$f_\mathrm{in}\left(TE\right)$$$; ii) compute the TE-independent fractions $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{iso}$$$ and $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}$$$ by estimating the slopes and intercepts in the following equations: $$\mathrm{ln}\frac{f_\mathrm{in}\left(TE\right)}{1-f_\mathrm{in}\left(TE\right)}=TE{\Delta}R^{\mathrm{en-in}}_2+\mathrm{ln}\frac{f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}}{1-f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}} \tag{2}$$ $$\mathrm{ln}\frac{f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}f_\mathrm{iso}\left(TE\right)}{f_\mathrm{in}\left(TE\right)\left(1-f_\mathrm{iso}\left(TE\right)\right)}=TE{\Delta}R^{\mathrm{in-iso}}_2+\mathrm{ln}\frac{f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{iso}}{1-f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{iso}} \tag{3}$$ where $$${\Delta}R^\mathrm{en-in}_2=1/T_{2,\mathrm{en}}-1/T_{2,\mathrm{in}}$$$ and $$${\Delta}R^\mathrm{in-iso}_2=1/T_{2,\mathrm{in}}-1/T_{2,\mathrm{iso}}$$$; iii) compute $$$T_{2,\mathrm{in}}$$$ and then $$$T_{2,\mathrm{en}}$$$ by estimating the slope and intercept of the following equation: $$\mathrm{ln}\left[S\left(b=0,TE\right)f_\mathrm{in}\left(TE\right)\left(1-f_\mathrm{iso}\left(TE\right)\right)\right]=-\frac{TE}{T_{2,\mathrm{in}}}+\mathrm{ln}S^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in} \tag{4}$$ where $$$S^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}$$$ is the intra-neurite signal at b=0 and TE=0.Animal model. Four adult male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 300-400g were used. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan. After the pre-occlusion MRI scans, rats underwent MCAo for 90 minutes as described elsewhere6,7.

MRI experiments. Experiments were performed on a home-integrated 3T whole-body MRI scanner containing an ultra-high-strength gradient coil with a maximum strength of 675mT/m8. A custom-designed, single-loop transmit/receive surface coil was used. A Stejskal-Tanner, segmented EPI pulse sequence was implemented in-house. Experimental parameters were: TE=50, 100ms; b-values(directions)=0(8), 0.5(12), 1.0(26) and 2.0(40)ms/µm2; diffusion-gradient separation and duration, Δ=24ms and δ=3ms. Other parameters were voxel-size=0.26×0.26×1mm3; matrix-size=96×96×20; repetition-time, TR=9s.

Data analysis. Signal denoising9 and distortion correction due to eddy-currents10, tissue-susceptibility differences11 and Gibbs-ringing12 were performed using MRtrix13. To assess $$$f_\mathrm{in}\left(TE\right)$$$ and $$$f_\mathrm{iso}\left(TE\right)$$$, conventional NODDI was fitted to each TE dataset using in-house Matlab scripts. Afterwards, Eqs. (2) and (3) were used to compute $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}$$$ and $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{iso}$$$. Finally, Eq. (4) was used to compute $$$T_{2,\mathrm{in}}$$$, and $$$T_{2,\mathrm{en}}$$$ was evaluated based on $$${\Delta}R^\mathrm{en-in}_2$$$.

In order to characterise the dependence of MTE-NODDI parameters on the intra-neurite parallel diffusivity, d||, we repeated the analysis for d||=1.0, 1.2 and 1.7μm2/ms (conventional value). Finally, as a means of quantifying the mean of MTE-NODDI parameters both in healthy and ischaemic tissue, Gaussian functions were fitted to the corresponding histogram peak.

Results and discussions

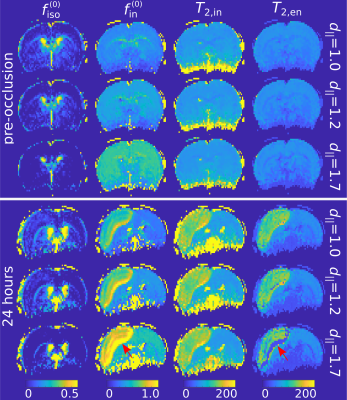

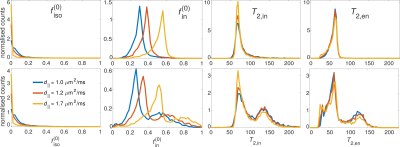

Fig. 1 depicts the MTE-NODDI maps for a single animal pre-occlusion (top panel) and 24 hours after stroke (bottom panel). Fig. 2 shows the corresponding histograms for the three values. Both the maps and histograms demonstrate that $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{iso}$$$ decreases, whereas $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}$$$ increases with increasing d||, as previously shown for conventional NODDI5,16. Conversely, $$$T_{2,\mathrm{in}}$$$ and $$$T_{2,\mathrm{en}}$$$ show negligible dependence on d||, also observed in the in vivo human brain5.Regarding the ischaemic tissue, both $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{iso}$$$ and $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}$$$ increase in the ischaemic area compared to the contralateral side, as previously observed for $$$f_\mathrm{in}\left(TE\right)$$$ and $$$f_\mathrm{iso}\left(TE\right)$$$7,17. However, we noticed that $$$f_\mathrm{iso}\left(TE\right)$$$ (data not shown), and consequently $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}$$$ (Fig 1-bottom, red arrows), tended to collapse to unity (physiologically unrealistic) if d|| was fixed to 1.7 μm2/ms (default value). In turn, as Eq. 2 is undefined for $$$f_\mathrm{in}\left(TE\right)=1$$$, estimating $$$T_{2,\mathrm{in}}$$$ and $$$T_{2,\mathrm{en}}$$$ is not possible. On the other hand, using smaller values for d|| provided more realistic values (i.e. $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}<1$$$). This is in line with the results of earlier works showing that geometrical changes, such as neurite beading, are indeed among the causes of the decrease in the intra-neurite diffusivity18.

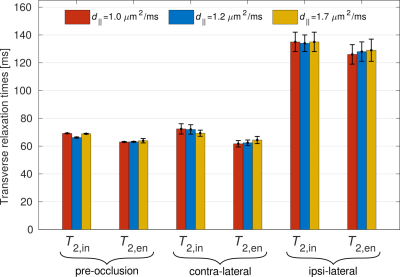

For $$$T_{2,\mathrm{in}}$$$ and $$$T_{2,\mathrm{en}}$$$, both are incremented in the ischaemic area compared to the contralateral side. Moreover, the relationship $$$T_{2,\mathrm{in}}>T_{2,\mathrm{en}}$$$, previously observed for healthy human tissue4,5, also holds for the case of ischaemic tissue. This can also be seen in the bar plot in Fig. 3, which shows the mean and standard deviation of the Gaussian functions fitted to the histogram peaks.

Conclusions

We have provided the initial insights into the application of MTE-NODDI to assess microstructural changes in ischaemic tissue in a stroke MCAo rat model. We first studied the dependence of the fractions $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{iso}$$$ and $$$f^{\left(0\right)}_\mathrm{in}$$$ on the fixed intra-neurite axial diffusivity and showed that they tend to have unrealistically large values if said diffusivity is fixed to the commonly used value 1.7μm2/ms. The latter poses a clear limitation to MTE-NODDI to study compartmental volume fractions in pathological tissue. Conversely, the relaxation times $$$T_{2,\mathrm{in}}$$$ and $$$T_{2,\mathrm{en}}$$$ showed almost no dependence on d||. This makes MTE-NODDI a useful approach for assessing compartmental relaxation times in both healthy tissue and pathology.Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Claire Rick for proofreading the abstract.References

1. Zhang, H., et al. NODDI: Practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage 2012;61:1000-1016.

2. Kamiya, K., et al. NODDI in clinical research. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2020;346:108908.

3. Peled, S., et al. Water Diffusion, T2, and Compartmentation in Frog Sciatic Nerve. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 1999;42:911-918.

4. Veraart, J., et al. TE dependent Diffusion Imaging (TEdDI) distinguishes between compartmental T2 relaxation times. Neuroimage 2018;182:360-369.

5. Gong, T., et al. MTE-NODDI: Multi-TE NODDI for disentangling non-T2-weighted signal fractions from compartment-specific T2 relaxation times. Neuroimage 2020;217:116906.

6. Wu, K.J., et al. Transplantation of Human Placenta-Derived Multipotent Stem Cells Reduces Ischemic Brain Injury in Adult Rats. Cell Transplantation. 2015; 24: 459–470.

7. Farrher, E., et al. Spatiotemporal characterisation of ischaemic lesions in transient stroke animal models using diffusion free water elimination and mapping MRI with echo time dependence. Neuroimage 2021;244:118605.

8. Cho, K.-H., et al. Development, integration and use of an ultrahigh-strength gradient system on a human size 3T magnet for small animal MRI. PLoS ONE 14:e0217916 (2019).

9. Veraart, J., et al. Denoising of diffusion MRI using random matrix theory. Neuroimage 2016;142:394-406.

10. Andersson, J. L., et al. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage 2015;125:1063-1078.

11. Andersson, J., et al. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage 2003;20:870-888.

12. Kellner, E., et al. Gibbs-ringing artefact removal based on local subvoxel-shifts. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2016;76:1574-1581.

13. Tournier, J.-D., et al. MRtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation. Neuroimage 2019;202:116-137.

14. Jelescu, I. O., et al. Design and Validation of Diffusion MRI Models of White matter. Frontiers in Physics 2017;5:61.

15. Novikov, D., et al. Rotationally-invariant mapping of scalar and orientational metrics of neuronal microstructure with diffusion MRI. Neuroimage 2018;174:518-538.

16. Howard A.F.D., et al. Estimating axial diffusivity in the NODDI model. Neuroimage 2022;262:119535.

17. Wang, Z. et al. Neurite Orientation Dispersion and Density Imaging of Rat Brain Microstructural Changes due to Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion at a 3T MRI. Current Medical Science 2021;41:167-172.

18. Budde, M. D., et al. Neurite beading is sufficient to decrease the apparent diffusion coefficient after ischemic stroke. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010;107:14472:14477.

Figures